|

|

MYSTERY OF THE

TEXAS TWOSTEP

CHAPTER SEVENTY ONE:

COUNTRY MUSIC

Written by Rick

Archer

|

|

Rick

Archer's Note:

We will return

to my story in the next chapter. In case you are

worried, I can at least reveal that I survived the surgery.

But I suppose

you already had that figured out.

|

|

JUNE 1980

OUTLAW COUNTRY

MUSIC

|

I loved my

friend Joanne dearly, but I could not stand her

country music. Nor could my students in the original

Die Hard class who insisted I begin teaching

Country-Western. They complained

about Joanne's music all the time. By and large, people who

loved Disco music despised Outlaw Country. There were

exceptions, but not many.

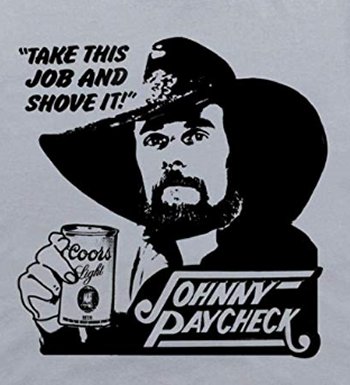

Outlaw Country

was male-dominated. Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Johnny Cash, Kris

Kristofferson, Merle Haggard, Johnny Paycheck, and Hank Williams

were the stars. Also known as 'Redneck Rock', Outlaw was very popular at Gilley's.

Outlaw Music was angry music. It was the music of

defiance and rebellion. Outlaw music embraced the Dukes of Hazzard

lifestyle: outracing the cops in a souped-up car, standing

up to the Man, telling your boss where to go, driving

pick-up trucks, getting drunk, blowing off steam, having a good

fistfight, smoking dope, hiding

contraband, doing the crime, doing the time, speaking

your mind. Oh, don't let me forget, kicking hippies'

asses and raising hell.

I suppose if I

had been raised country, all those songs about drinkin', cheatin' and carryin' on

would have made me feel right at home. But I was

not raised in the country, I was raised in the city.

My music tastes were the Doors and the Rolling Stones.

Was not much of a Beatles fan, but I added Santana,

Fleetwood Mac, and the Eagles in the Seventies.

|

|

Then came Disco.

Okay, I agree a lot of the music was silly. But Disco

music was not meant to be complicated or insightful.

It was meant to be hypnotic. I have to be

honest, my love for Disco music poisoned all tolerance when

it came to Twang. There was something about exaggerated nasal wailing that rubbed me

the wrong way. Now, mind you, if someone else liked

this music, more power to them. I'm a live and let

live kind of guy. I was not going to burn records just

because I did not like the music. But try as I might,

I just could not force myself to like Twang and Outlaw

music.

|

|

Joanne's idea of a good dance song was 'Up

Against the Wall, Redneck Mutha'. During our

lessons, she played this song incessantly. At least

five times an hour she reminded me to

listen carefully so I could catch the beat.

Considering she knew darn well how much I disliked this

song, I think Joanne kept playing it to punish me for having such a

bad attitude towards Country. But with music like

that, who could blame me? I won't deny it. I was a country

music bigot.

But here's the

funny thing. I liked the C&W music they played at

Cowboy just fine. It was not until our May visit

to Gilley's that I realized there was

something sneaky going on with country music. During the Western Era, there were all sorts of

mysteries. Now I had uncovered another one.

There

was only one kind of Disco music, so why were there two

kinds of Western music? As usual

with these mysteries, it was not till I began

writing my book 40 years later that the Internet

gave me my answer.

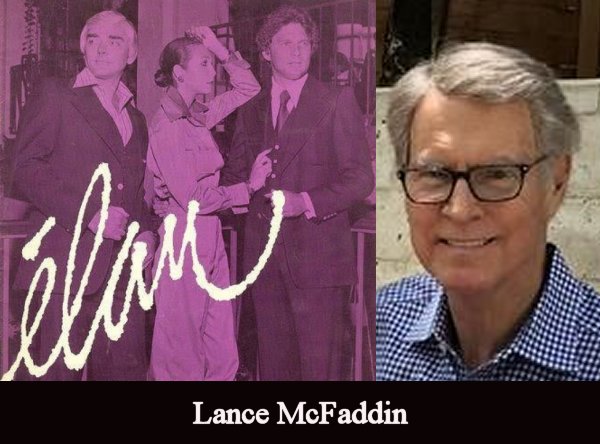

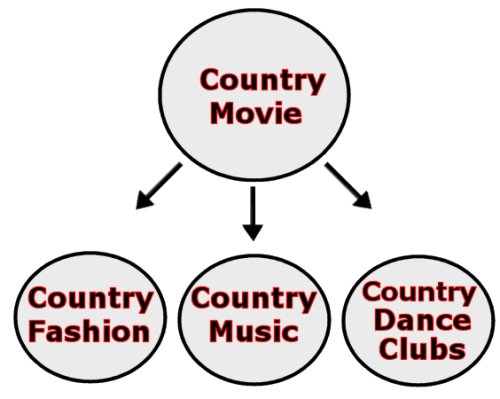

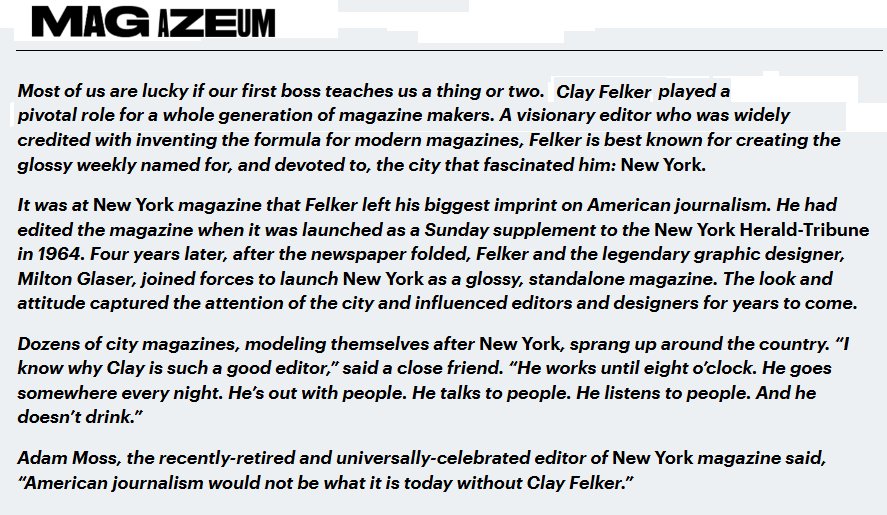

Although Clay

Felker may have had a hand in this music mystery,

the best answer lay with two men: Irving Azoff,

music impresario, and Lance

McFaddin, owner of Cowboy.

|

FLASHBACK TO FRIGHT

NIGHT

PEACEFUL EASY

FEELING

|

"Although I was a nervous wreck, Fright Night

had opened my eyes in so many ways. Apparently

it had opened my ears as well.

Totally by accident, the combination of four beers and lots of practice

had allowed my mind to become more

receptive to the music. I noticed how my

feet

were moving to the beat of the music. Technically speaking, I knew all along

how

the music

was supposed to fit the steps,

but I had never 'felt it' before. It was so much easier to dance now

that the rhythm of the music guided me.

Lap after lap,

Sally

and I floated

around the floor. Some of this music was really pretty! I started to grin.

I could not believe

I was

actually enjoying listening to Western music. To my

surprise, the music at Cowboy was a lot better than I had expected. I didn't like every song, but in general I

liked the music a lot. I even caught myself humming to

some of the songs.

Late in

the evening I

was shocked

to hear the familiar strains

of

'Peaceful Easy Feeling',

a classic Eagles song from their first album in

1972. I had seen the Eagles perform a free concert in

Denver during my time at Colorado State University. It

was love at first sight. Or maybe 'first

listen' would be more accurate. I played the

Eagles' first album

non-stop throughout my year of Vanessa-Fujimoto misery.

I loved 'Witchy Woman' and of course 'Take

it Easy' became one of my all-time favorite

songs.

I

noticed that

Peaceful Easy Feeling was the perfect speed for

the Texas Twostep. Good grief, I

had no idea some of my favorite songs were actually

Country-Western music in disguise. I was delighted at

my discovery. Maybe Country-Western music

isn't so bad after all."

|

THE MAN WHO CHANGED

COUNTRY MUSIC

|

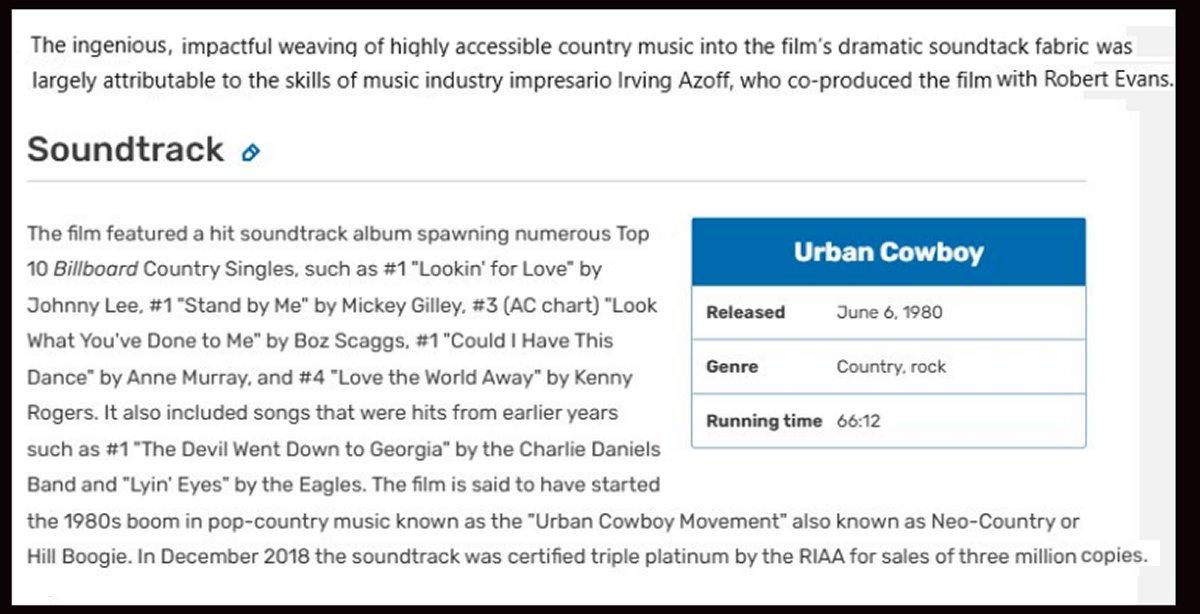

Excerpts from 'Urban

Cowboy Turns 35',

-- written by John Spong, Texas Monthly,

June 2015,

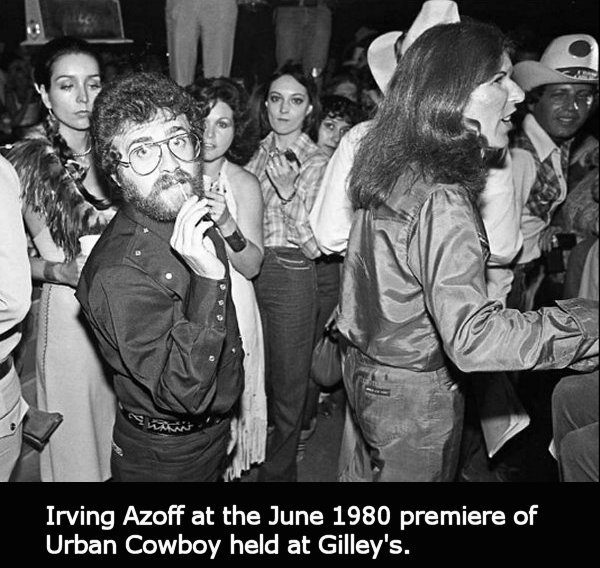

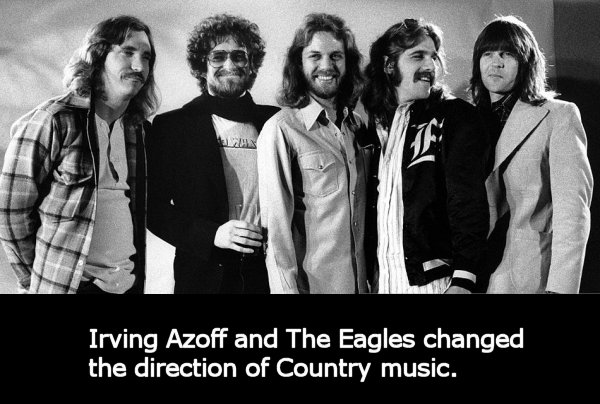

"The rights

to produce the movie were won by Irving Azoff for an astounding

$200,000. Azoff quickly partnered with

Paramount Pictures. Azoff was a music guy,

an L.A.-based manager who oversaw the careers of

huge acts like the Eagles and Steely Dan."

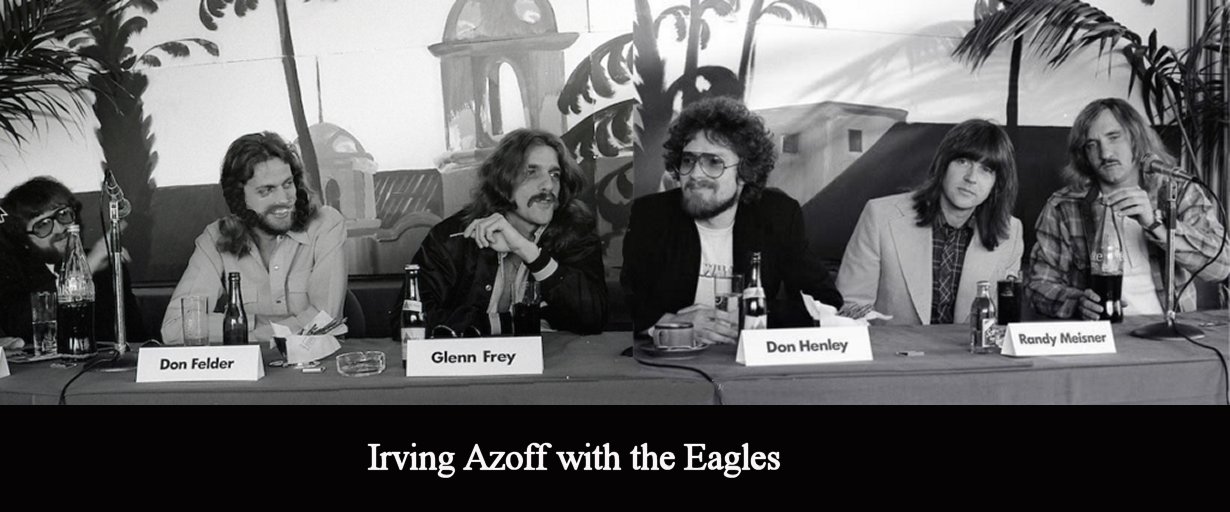

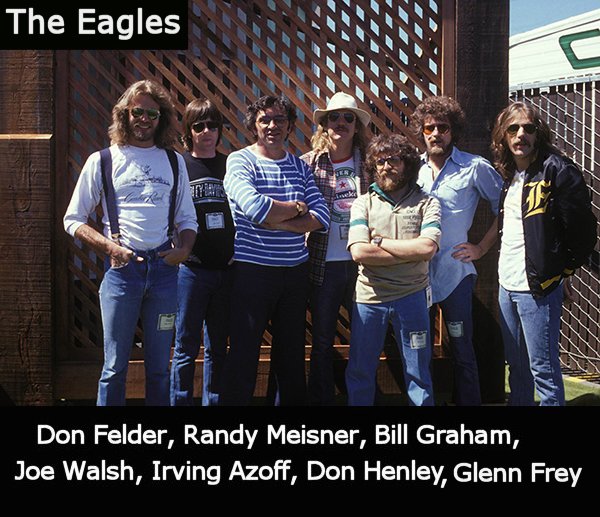

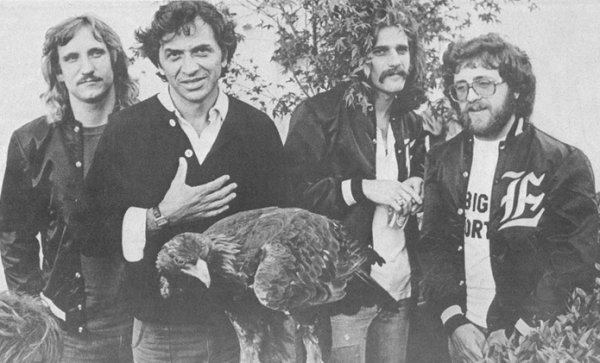

Irving Azoff got his start as manager of the Eagles.

Branching out, he began to represent other music

clients as well.

In 1978

Azoff purchased the right to produce Urban

Cowboy. That allowed him to pick the

music for the soundtrack. The next thing he

did was fill the soundtrack with music recorded by

the clients he represented.

Irving Azoff

was the man who singlehandedly changed the direction

of Country-Western music.

|

|

In 1998 the Eagles

were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Don

Henley immediately pointed to Irving Azoff in the audience,

then said, "Without Irving, we wouldn't be

standing here

today!"

Glenn Frey,

standing next

to Henley on stage, quipped, "Well, Don, we might have

made it here on our own, but we wouldn't have made nearly as much

money."

Henley laughed,

then added, “You're right, Glenn. Irving may be Satan, but he’s our Satan!”

Legend has it that Azoff smiled.

The Eagles were

unanimous. They knew their big break was getting Azoff to manage them. One can imagine Irving Azoff

felt the same

thing about the Eagles. Irving Azoff was

the same age as the members of the band. Considering them his

buddies in addition to his clients, Azoff developed a fierce

loyalty. Under his tutelage, the Eagles became the

best-selling band in America during the Seventies.

Five number-one singles, six number-one albums, six Grammy

Awards and five American Music Awards.

Something of a straight

arrow, Azoff never took

to drugs. He preferred to keep

his wild child

wunderkinds under control.

“Artists,” Azoff

said, “like to know the guy flying the plane

is sober.”

Not only that,

Azoff had the Svengali touch. He made his

clients rich with a ruthless negotiation style.

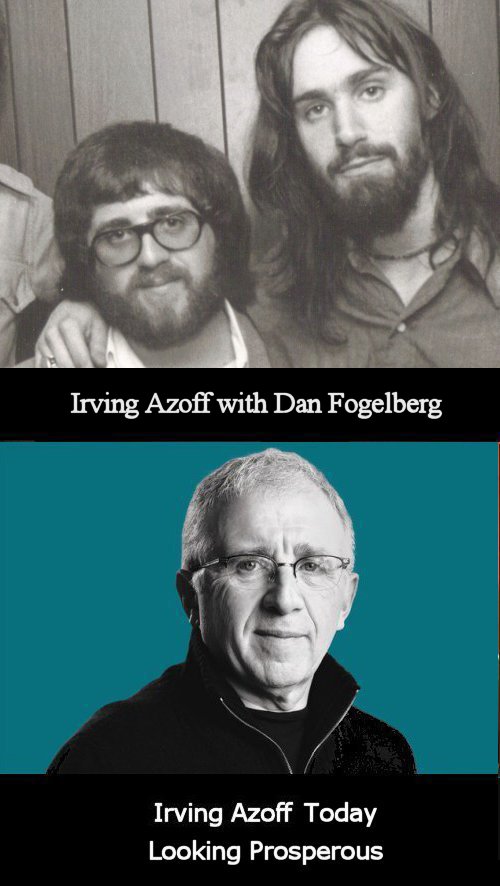

Azoff had

gotten his start as the hotshot manager of the

Eagles. After turning them into the hottest band in the

country, Azoff added to his stable with Seventies

artists such as REO Speedwagon, Steely Dan and Dan Fogelberg.

Prior to

Urban Cowboy, Azoff had already noticed a

new trend taking place in country music. Although

Saturday Night Fever Disco tunes dominated the

airwaves in 1978, behind the scenes in the world of Country

music, Azoff sensed a potential revolution. An emerging sound best described as 'Country Rock'

was going head to head with the hard-edged

Willie and Waylon 'Outlaw' music.

The Byrds,

Buffalo Springfield, plus Crosby, Stills and

Nash were the forerunners.

Emerging artists such as Neil Young, Bob Dylan, Pure Prairie League, Creedence Clearwater and

the Grateful Dead also tied their fortunes to 'Country

Rock'. However, no one dared

whisper that these so-called rock bands were actually playing country

music. It was a taboo subject.

I had no idea I was

listening to covert country music. Considering how

prejudiced I was against Twang and Outlaw, it was probably just

as well I did not know many of my favorite songs were secretly Country.

Neil Young's Heart

of Gold, Bob Dylan's Lay Lady Lay and

Pure Prairie League's Amie came

dangerously close to crossing the forbidden line.

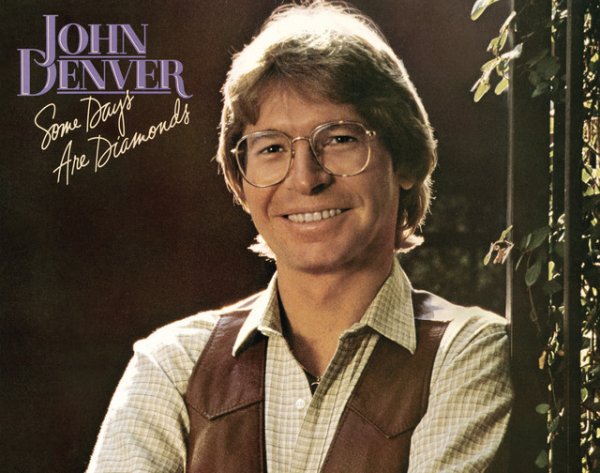

John Denver was

another

trailblazer. I loved his song Country Roads.

Looking back, the title even had the word 'Country'

in it, but I was too stupid to know this song had started as

a C&W hit before crossing over to mainstream popular

music. Nor did I know that Denver was considered a

traitor by the purists.

The winds of change were

apparent at the 1975 CMA Awards. This was the year

John Denver beat out Loretta Lynn, Waylon Jennings, Ronnie Milsap, and Conway Twitty as the Country Music Association 'Entertainer

of the Year'. The presenter, Charlie Rich, was so

disgusted by Denver's victory he burned the piece of paper announcing Denver as

the winner on the stage. Right or wrong, the incident

was seen as a protest in defense of traditional country

music against pop usurpers.

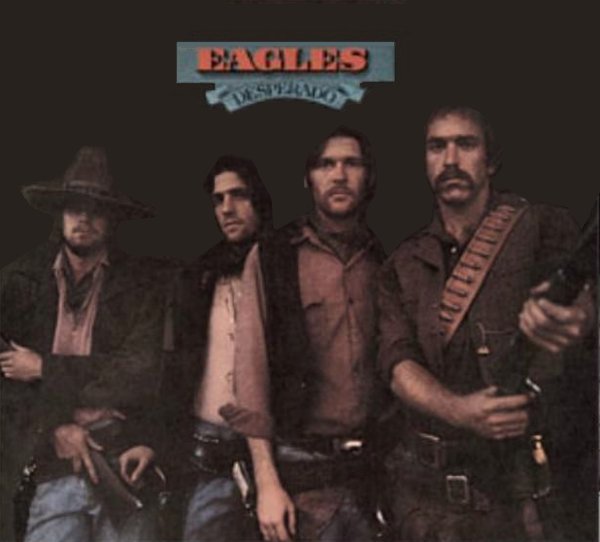

The Eagles were

pioneers in

the formation of this new

'Country Rock'

style of country music.

With songs like

Peaceful Easy Feeling, the Eagles crafted a

sound that synthesized elements of country music

and rock. The Eagles were gifted song writers.

Indeed, many of their songs told a complex story.

As opposed to Disco music and Rock music with their inane,

repetitive lyrics, the Eagles found that country-style

ballads such as Lyin' Eyes and Tequila Sunrise

worked better to country music formats.

At the same time the

Eagles were rockers at heart. They found a way to make

country-style vocal harmonies blend to a rock beat in songs

like Bitter Creek and Outlaw Man.

Their music found a wide, appreciative

audience (including me). Although Desperado,

the Eagles' second album, was at best a so-so commercial success in

1973, I adored this album.

Little did I know the deliberate Western theme of Desperado was paving

the way for a music revolution.

Irving Azoff parlayed his triumph with the Eagles into

managing a veritable Who's Who list of American recording

artists during the '70s. However, the

Eagles were always closest to his heart. Azoff was to

the Eagles as Robert Stigwood had been to the Bee Gees.

Although Azoff did not care much for Disco music, he noticed

how Stigwood had used the Saturday Night Fever

soundtrack to turn the Bee Gees into superstars.

I do not know

this for a fact, but I have a strong hunch Clay Felker phoned Azoff.

"Listen, Irving, I've got

this C&W dance movie starring John Travolta. I bet you could do for the Eagles

what Robert Stigwood did for the Bee Gees."

Clay Felker had

created Urban Cowboy by copying Robert

Stigwood's playbook. Now it was Azoff's turn. Thanks

in large part to the Eagle's success during the Seventies,

Azoff had the money necessary to win the 1978 bidding

contest to produce Urban Cowboy.

Azoff put up the big bucks because he knew a rare opportunity had

crossed his path. He

bought the movie rights specifically to showcase his

talented stable of music artists including the Eagles.

In so doing,

Azoff would personally change the direction of country music.

Azoff

believed that Disco music would soon run its course.

The soundtrack for Saturday Night Fever

had

brought in millions. Why not give Country music a

similar chance? Azoff

knew what he was doing. By

securing the rights to Urban Cowboy, Azoff bet the farm he could do for the Eagles what Stigwood had done

for the Bee Gees by using their music on the movie

soundtrack.

This

bold,

strategic move came at the perfect time in Azoff's

spectacular career. Having witnessed

first-hand the widespread acceptance of the emerging California

soft rock sound...

Jackson Browne, the Eagles, Linda Ronstadt... it was Azoff's

good fortune that Urban Cowboy came along at

just the right time. This was the opportunity Azoff needed to take his

preferred country rock sound to the next level.

It was a shrewd

gamble.

Azoff packed his

Urban Cowboy

soundtrack with many

of his own artists such as Boz Scaggs, Dan Fogelberg, Jimmy

Buffett, Linda Ronstadt and of

course the Eagles. Then Azoff took a page from Robert Stigwood

and released the album well

in advance of the movie. The soundtrack sold like

hotcakes, but not without controversy. Immediately there were howls

of protest. Where's Willie Nelson? Where's

Waylon Jennings? The answer should have been

obvious... Irving Azoff was deliberately steering the

direction of country music towards the new California sound.

Azoff did not

stop there. Following the

Stigwood playbook to the letter, Azoff understood the movie could

impact the way people dressed, danced, and

listened. The potential

for tie-ins was phenomenal. There is ample

circumstantial evidence to suggest Irving Azoff and Clay Felker

contacted the fashion industry.

What other explanation

could there be for the Western fashions that flooded Houston

well over a year in advance of the debut?

It is my theory

that Clay Felker and Irving Azoff worked hand in hand with

Lance McFaddin, proud owner of élan, Houston's swankiest nightclub.

In addition to élan,

the crown jewel, McFaddin-Kendrick operated a series of posh Houston nightclubs in the Seventies and Eighties.

Confetti, Ocean Club, Todd's,

Rialto,

Studebakers, Foxhunter, Acapulco Bar, Rodeo

and Cowboy were extremely popular

McFaddin-Kendrick properties. Each place was lavishly decorated each

was located in the high-rent Galleria area frequented by

affluent professionals.

Both Felker and

Azoff spent an inordinate amount of time in the Houston area

during the planning stage of Urban Cowboy.

What better place to hang out at night than the luxurious

elan? I doubt it was a coincidence that

McFaddin's elan was prominently featured in

the movie. Given that Lance McFaddin spent three

million dollars on his ground-breaking western club

Cowboy and a similar amount on Rodeo,

it is obvious someone tipped him off in advance. Given

the magnitude of the risk in McFaddin's Cowboy

gamble, I am sure Felker was involved.

Why was the

country music at Cowboy totally different than

the music at Gilley's? For this I credit

Irving Azoff. I have a strong

hunch Azoff explained his decision regarding the new

direction of country music to McFaddin.

"Lance, you

are in the nightclub business. I am in the music

business. My gut tells me Country Music is ready to

head in a different direction. I know that Clay

(Felker) has already persuaded you to invest in Cowboy

to take full advantage of the coming western trend.

Now it's my turn. I suggest you consider playing the kind of C&W music I

will

feature on the Urban Cowboy soundtrack."

One

reason why I believe Azoff and McFaddin had a serious talk

was McFaddin's obsessive attention to detail.

"During the Disco

Era of the Seventies, McFaddin Ventures in Houston, Texas,

commissioned a study on the stimulation of males and females

during the playing of music. They accordingly custom-tuned their

speakers to make their numerous properties more exciting. Karin

Cook, their music programmer and head disc jockey, trained other McFaddin Ventures

disc jockeys to work the music format - 6 up, 3 down - as a way to

sell more drinks." (Wikipedia)

In other words,

Lance McFaddin made it his business to pay attention to music trends, even

down to which Disco format sold the most drinks. For this reason I

imagine Azoff's insider tip convinced McFaddin

to commission similar research regarding what kind of C&W music would be

most acceptable to his professional clientele at Cowboy.

No doubt the research revealed the emerging

country-rock sound characteristic of the Eagles was

definitely the

direction to go.

The craziest

part of McFaddin's decision was to include Disco music in

the format. That was unheard of. If someone had

played a Disco song at Gilley's, there would

have been a brawl. But McFaddin instinctively realized

the majority of his customers liked Disco music just as much

as they enjoyed Azoff's emerging style of Western

music. Why not play both?

Ah, the winds of

change.

Cowboy was so successful that other Houston night clubs

quickly jumped on the C&W bandwagon. In so doing,

Houston's Western Transformation destroyed every Disco in

the city. Following its success

with Cowboy, McFaddin-Kendrick

launched a national chain of 40 western clubs that mixed

country music with disco. All because Clay Felker

waved his magic wand and said, "Let there be Western."

|

|

|

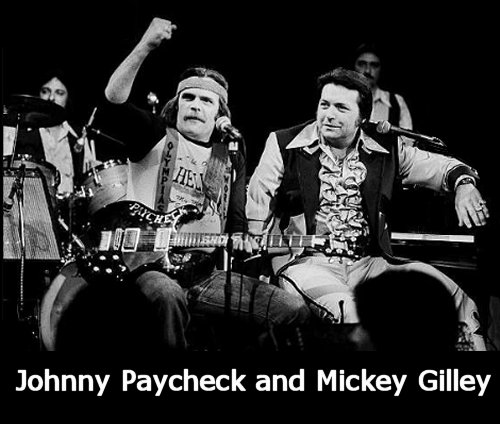

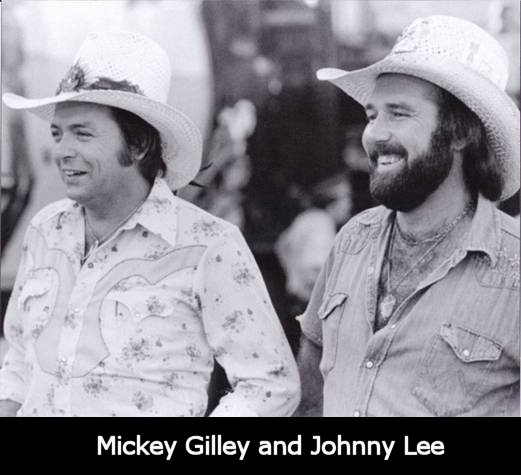

Filming on

Urban Cowboy was scheduled to begin at Gilley’s

in May 1979. One night country singer Johnny Lee was

on break when a

stranger approached him. The newcomer was a short, pudgy

Jewish guy. Wearing the wrong kind of clothes

and thick glasses bigger than his face, this little guy stuck

out like a sore thumb at the rough and tumble honky-tonk.

At first glance, Johnny Lee was not impressed.

But he also noticed the man was quite sure of himself.

Identifying himself as the Urban Cowboy

producer, Irving Azoff wasted

no time making his pitch. "Would you be interested in

singing in a movie?"

Accustomed to

being courted by would-be 'managers' and 'I’m-going-to-make-you-a-rock star'

hustlers, Lee decided to humor the guy. Rolling his

eyes, Lee replied, “Yeah, buddy, sure, whatever, let me know

when,

I'll sing in your movie.”

Johnny Lee's

recording of Lookin’ for Love was released in June 1980,

the same date as the movie's premiere. The song

quickly became the breakout hit on the Urban Cowboy

soundtrack. Lookin’ for Love stayed on the charts for 37 weeks. The song peaked

at No. 1 on the Billboard Hot Country Singles and No. 5 on

the pop charts. A country-western song high on the pop

charts? Virtually unheard of. What was going on

here?

Country music

would never be the same.

|

Johnny Lee would

later reminisce.

“You have to

understand, people were coming in all the time promising

this, saying that. Azoff came out one night and

heard me do “Cherokee Fiddle” which was a

big hit for me in Houston. He said, “You want to

sing it in a movie?” Well, people were bullshitting me

all the time. So I said, “Yeah, sure, just as soon as I

finish this watermelon. You bet.”

I thought Azoff was just

somebody feeding me a line of baloney. I blew him

off and went on drinking my beer. So when it

actually happened, it freaked me out.

That movie

broadened the audience that listened to country music.

A lot of people started listening to country music and

going to country dance halls that never did before. It

gave country music a shot in the arm. It was a fun time,

and it absolutely was the best thing that ever happened

to me in my life."

Frankly

speaking, much of the 'Outlaw Sound' was tough to listen to for

everyone but hard core country types raised on twang and

rockabilly. While there are many purists who will

disagree ('Urban Cowboy ruined country music!'),

Azoff guessed correctly that Country

Rock with its harmonies and intricate lyrics would appeal to a wider audience.

What most people don't know is that Irving Azoff bet the

farm on his instinct. There was no guarantee his

gamble would pay off, but Azoff foresaw

Robert Stigwood's soundtrack maneuver with Disco could be

replicated with Country. The Urban Cowboy soundtrack became the

fourth best-selling album of all time.

I give Irving

Azoff a lot of credit. Today Urban Cowboy

is credited with popularizing a pop-influenced style of

country music known as 'Country Rock'. This

subgenre featured melodic tunes with a soft rock

sensibility. The soundtrack spawned several hit

singles that achieved crossover success on both the country

and pop charts. By shifting away the harder-edged

Outlaw country sound, Country Rock moved towards an

easier-listening style that was more palatable to mainstream

tastes.

Wildly

successful at virtually every stage of his career, in his

later years Irving Azoff would emerge as the

most powerful man in the music industry. Azoff would

often comment that his Urban Cowboy gamble was

the move that sent his career into the stratosphere.

|

|

THE REDEMPTION OF

CLAY FELKER

|

|

Throughout the early part of 1979, my head was swirling with

the impending Western takeover of Houston. I was as

lost as a boy can be. As one Disco dance club after

another folded and the new western fashions began to appear,

I knew someone had to be responsible. But

who, I asked, had the influence necessary to orchestrate

such dramatic changes?

No matter how hard I studied the changes, I remained

clueless about the reasons. With my career in

jeopardy, my questions went unanswered. As it turned

out, Clay Felker's manipulations would remain a mystery to

me for thirty more years. Fortunately the Internet

came along to put me out of my misery.

Rumor has it

that

New York sets the pace for the rest of the

country. After all, New York is the epicenter

of seven glamour industries - finance, news media,

advertising, book publishing, theater, fashion, and fine

arts. New York has serious players in TV, music, and movies as well.

No doubt decisions made in these New

York industries affect us on a daily basis, but rarely are

we told what goes on behind the scenes.

The story of

Clay Felker demonstrates how

the ultimate New York insider was able to singlehandedly

create a Western trend that swept the nation. The story of his

involvement in Urban Cowboy

serves as the perfect example of how a New York power

broker can make decisions that influence the lives of many

people.

|

|

Clay

Felker used the experience he gained at his former magazine to

know how the

power game is played.

It is obvious that Felker knew someone important in every single

one of those power industries. Like a modern day Wizard of

Oz, Felker lined up his contacts and brought them to the

table to support his effort. In the case of

Urban Cowboy, four different

industries got rich - the movie industry, the country music industry, the

fashion

industry with its western wear, and Houston's local nightclubs.

Thanks to the coordinated effort by the fashion industry, the music

industry, and the movie industry, America's preoccupation with Urban Cowboy

started long before the movie made its debut.

Indeed, businessmen in several different industries were so sure

Urban Cowboy would be a success that they rushed to

get in on the ground floor. Their advance knowledge of this

project was license to print money. Lance McFaddin is a good

example.

Inside knowledge is a powerful thing.

What else would explain why the new Western fashions

began flooding the marketplace well in advance of the actual

movie itself? The music was changing as

well.

Once the filming started in the summer of 1979, not a day

went by without some breathless press release on

John Travolta's latest escapade. With Houston gaga

over Travolta, I have no doubt the amazing cultural trend towards all things

Western here in my hometown was manipulated by Clay Felker's unseen hands from start to

finish. Clay Felker and his media machine were pushing our buttons before we ever knew what

hit us.

|

|

|

In the March

2009 issue of Texas Monthly, writer

Christopher Kelly pointed out that Urban

Cowboy was a success to the tune of $47

million dollars. Author Kelly called the

success of the movie an "unlikely feat"

and attributed its "unexpected success"

to the movie's "exquisite timing".

I believe Christopher Kelly was referring to the uncanny

good fortune of finding a story that could

capitalize on the energy of John Travolta and the

Saturday Night Fever so quickly. As

the saying goes, 'strike the anvil while the

iron's hot'. We now know the 'exquisite

timing' of Urban Cowboy was no

accident, but rather Clay Felker's clever

exploitation of a unique opening.

By publishing

Aaron Latham's Gilley's story in

Esquire, Clay Felker was deliberately

following the same path that Nik Cohn had laid out

two years earlier for Saturday Night Fever. So what if

Felker was a copycat? He didn't care.

Clay Felker was in a cynical mood. He was

bound and determined to create a 'disguised sequel'

to Saturday Night Fever to make it

easier to

sell the movie rights.

|

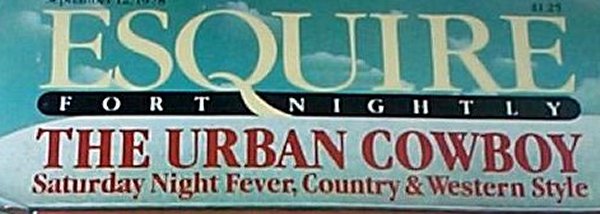

Clay Felker couldn't come right out and say 'Sequel',

but he found an effective way to convey the message

nonetheless.

The subtitle to Aaron Latham's Esquire story said it

all:

'Saturday

Night Fever, Country-Western Style'

Clay Felker wasn't

interested in subtlety. Felker

intended to link this

story

to Saturday Night Fever from the start.

He was going to make sure every reader of the Urban Cowboy

tale had the 'Sequel'

concept firmly implanted in

their brain.

|

|

So what

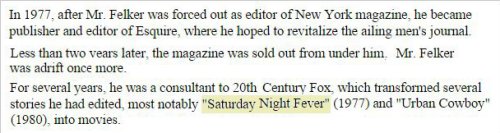

happened after the movie rights were sold to

Paramount? Unfortunately, since Urban

Cowboy took place long before the Internet,

I could not find any stories

that tracked

his activities from the publication of the Esquire article in September

1978 to the movie premiere in June 1980. There are snippets, but

they are thin at best. Here is what little I

know. Clay Felker was unable

to restore Esquire to prominence. He left Esquire

shortly after the Aaron Latham story. In 1980-1981

Felker served

as editor for the New York Daily News. That was

a short stay at best. Felker may have also worked for the

Baltimore Sun, but I am not sure about that.

After the

premiere, Felker held a position in Hollywood as a consultant

and producer to 20th Century Fox. However, from

what I gather, Felker accomplished very little. After that, little of note.

|

|

|

Another mystery is

what Mr. Felker's cut might have been from the Urban

Cowboy project. My guess is that Felker and

Aaron Latham had an understanding. Felker would work behind

the scenes while Latham would act as

front man.

Indeed Latham stayed on

board as script writer and right hand man of director

Jim Bridges.

What was Felker doing? One can assume he pulled

strings behind an invisible curtain, but when, where, and

how is strictly conjecture. Given that Felker's

contributions are left to the imagination, my guess is that

Felker wanted it this way. If asked to speculate, I

think Felker was in charge of publicity. I imagine he

worked the phones day and night. Calls to Hollywood,

calls to Houston TV stations, calls to Houston newspapers,

calls to national magazines, calls to influential media

moguls.

Clay Felker's

exact role may never be known, but give the man credit. The entire scenario

was meticulously laid out two years in advance of its June

1980 debut. What Felker accomplished was

a master

stroke indeed.

My guess is that Clay Felker worked for a percentage of the

profits. Clay Felker turned his fantasy into $47

million dollars. Given whatever his percentage was,

Felker may have walked away as a millionaire.

If so, he

deserved every penny.

Gilley's was no prom

queen, believe me. Felker took an ugly, smelly

dump and persuaded the planet that this run-down joint was

somehow special. The number one tourist attraction in

America? It boggles the mind. This was the equivalent of putting a

tutu on a hippopotamus and convincing audiences

they are witnessing a prima ballerina. That might work

for Fantasia, but only Clay Felker could do

the same for Urban Cowboy.

I

found Clay Felker's personal story to be very compelling.

For one thing, his talent was undeniable. However, it isn't always talent that turns into success.

In Felker's case, he also had the toughness

to thrive in a highly competitive atmosphere. Felker

got knocked down more times than most people. Each

time he was down, he got back up, dusted

himself off, and successfully climbed back on top.

|

Let's face it, Clay Felker was badly burned on

Saturday Night Fever. After Nik Cohn played him, Felker

had to be appalled to see Cohn's dubious Disco story strike

it rich. One can only imagine what went

through Felker's mind as a conman turned a hack

article into one of the most famous movie of the

70's

right up there with the Exorcist and Godfather. In a sense, perhaps Felker deserved

this embarrassment due to his negligence. No doubt

Felker was distracted with his financial problems at the magazine.

We all make mistakes, yes? But how many of us are

clever enough to find a silver lining in our

mistake? Clay Felker didn't get mad, he got even.

|

My

favorite part of the Clay Felker saga was how he carefully

exploited the Robert Stigwood playbook. Felker had the sense to

learn from his mistake in a very unique

way. Which leads me to a question. Would I have

had the foresight to do the same? Probably not.

Clay Felker could see

things that other people couldn't. Here is an

article from Texas Monthly which

proves my point.

Looking for Love: The Urban Cowboy

Rides Again

-- written by Gregory Curtis,

editor of Texas Monthly, Nov.

1998

"Clay Felker

was the editor of Esquire. Our publisher Mike Levy and

Bill Broyles, my

predecessor as editor, invited Felker to Houston

that summer to speak at the Rice University Publishing

Program. Instead of an honorarium, Felker wanted to be shown

around the famous boomtown. So they ended up at Gilley’s

late one night.

Felker saw the mechanical bull and the cowboys dancing with

a beer bottle in their back pockets and their girlfriend’s

thumbs hooked in their belt loops. He was so struck by the

place that back in his hotel room late that night, he called

writer Aaron Latham. Felker told him to get out of bed and catch the first

airplane to Houston. The rest is history.

Here at Texas Monthly, we had discussed writing about

Gilley’s

but hadn’t done it yet. One of the aggravations of journalism is

that you can be so familiar with something that you miss a

story that is right in front of your face. That was what we

did with Gilley’s.

Felker saw it and we didn't."

The story of Urban Cowboy offers a close look

at how a powerful man can affect an entire country with his

magic wand. Clay Felker created a mythology that Gilley's

was some sort of country-western paradise and somehow got an

entire country to believe him. Felker parlayed

something close to thin air into the score of a lifetime. Who else besides Clay

Felker could have pulled this off? I

tip my hat to the Wizard.

Unfortunately there

is not much

to explain what happened to Clay Felker after the movie

premiere. In 1984 Felker

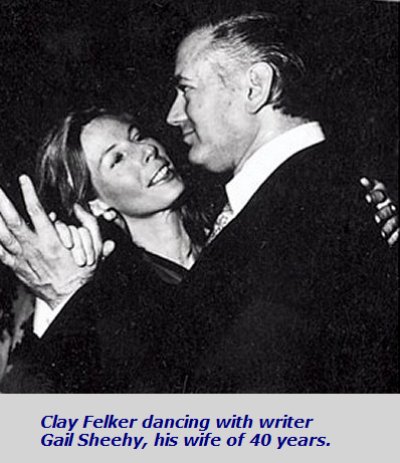

married Gail Sheehy, the talented writer who was the love of his

life. My guess is they lived handsomely on earnings

from Urban Cowboy.

Clay Felker

passed away in 2008.

He was survived by

Ms. Sheehy.

Clay

Felker had been reduced to a mere footnote during the Saturday Night

Fever glory ride. Over the next year,

Felker

kicked himself every day for letting Stigwood

profit off a story that slipped right under his nose.

Considering he was

known for seeing things that others missed, no doubt Felker

had been badly humbled.

However Felker learned a valuable lesson during his downfall. During his career at New York

magazine, Felker had made some money for himself, but mostly for

other people. The time had come

to put his unique experience and extraordinary

talent to good use. Felker had one other advantage.

Sometimes it isn't what you know, but who you know. Felker was

gratified when some of

America's most influential people were more than happy to take his

phone call. This was the

Redemption of Clay Felker.

Urban Cowboy

stands as the

supreme validation of his prodigious ability.

|

|

THE TEXAS TWOSTEP

CHAPTER SEVENTY two: ORDEAL

|

|

|