|

|

|

|

Part Three: History of

the

Julio-Claudian Emperors

Story written

by Rick Archer

November 2009

|

|

THE

TALE OF SIX CAESARS (PLUS ONE)

1 Julius

Caesar - The Man Who Ended the Republic

2 Augustus

Caesar - The Man Who Was First King

3 Tiberius -

The Man Who Did Not Want to be King

4 Sejanus -

The Man Who Barely Missed becoming King

5 Caligula -

The Man Who Should not Have been King

6 Claudius -

The Man Who was too Stupid to be King

7 Nero - The

Monster Who Ended the Julio-Claudian Line

|

Forward

You have all heard of ambition gone mad, corruption, and dirty

politics. You have all heard of political assassination. You

have all heard of sexual perversion, cruelty, and debauchery.

This story has it all. So where do you want me to start?

American politics can

be pretty rough sometimes, but we cannot even begin to hold a candle

to the Romans. There is no way to explain how stunning some of

these stories are. I could barely comprehend or believe some of the

stories I read while researching for this article.

Now I am going to

share them with you. If there is one word that could describe this

era, it would be "excess." The Romans did everything to

excess. Too much killing. Too much sex.

And too much cruelty.

Endless cruelty.

Look no farther than

the savage blood sport recreation of the Romans - watching slaves

bash their comrade's brains in during gladiatorial contests,

watching defenseless Christians slaughtered by fierce animals,

torturing criminals in public for amusement, watching helpless

animals abused in all sorts of hideous ways, laughing and jeering at

the suffering - and you begin to comprehend this was a

horrible, violent society.

Why they call it the

"Roman Civilization" is a mystery. These people were NOT

civilized.

These events occurred

two thousand years ago. Therefore I cannot promise that

everything I have written is the truth since I had no choice but to

rely on the accounts of others before me.

You can assume,

however, that everything I write was faithfully copied from research

I did on the Internet. My main source, of course, was the

amazingly helpful Wikipedia.

What I mean to say is

that no matter how outrageous the story is, you have my absolute

promise I did not make it up. I read it, gasped in amazement,

then looked at several more sources to see what they had to say.

I found there is strong consensus on even the most outrageous of

tales. And now I am passing it on to you.

This is a long

tale. Let me assure you of one thing - once you start reading

it, you won't want to stop. RA

This story is told in

four parts.

|

Augustus Caesar, the Greatest of them All

|

|

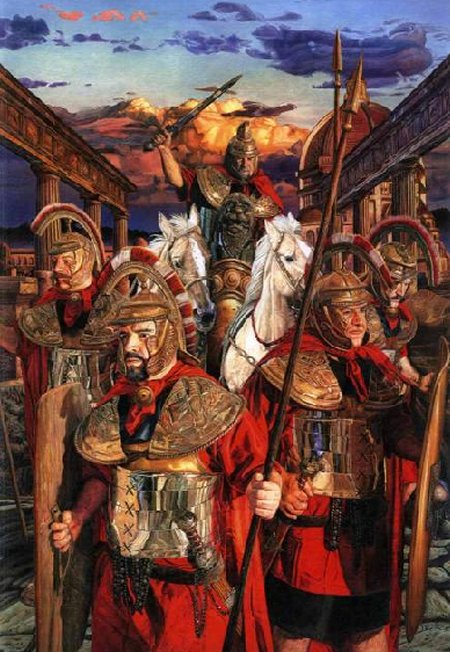

The

Julio-Claudian Dynasty

The term

Julio-Claudian Dynasty refers to the series of

the first five Roman Emperors. These men ruled the Roman

Empire from 27 BC to AD 68, when the last of the line, Nero,

committed suicide. The dynasty is so named from the

family names of its first two emperors: Gaius

Julius

Caesar Octavianus (Augustus) and Tiberius

Claudius

Nero (Tiberius). The ruling line was founded upon an

alliance between these two families.

The

5 Emperors of the Dynasty:

1.Augustus ( 27 BC– AD 14)

2.Tiberius (14– 37)

3.Caligula (37– 41)

4.Claudius (41– 54

5.Nero (54– 68)

|

|

|

|

|

3 Tiberius - The Man Who Did

Not Want to be King

Born 42 BC,

the Second Roman Emperor (AD 14 - 37 AD)

Tiberius Claudius Nero ascended to Emperor in 14

AD. To help put things

into historical perspective, Jesus Christ walked the earth

during the reign of Tiberius. However, it is quite

unlikely that their paths ever crossed. Tiberius was

the second Roman Emperor.

The story of how

Tiberius came to succeed Augustus is nothing short of

remarkable. Tiberius was the longest of all long shots. Tiberius was, at best,

fourth or fifth in line to succeed Augustus.

Furthermore, as it was, his adopted father Augustus hated his

guts.

Tiberius was the

stepson of Augustus. Shortly after Tiberius was born, his

mother Livia had divorced Tiberius' father in

order to marry Augustus Caesar. Although Tiberius grew up

in the house of Augustus, there was absolutely no "father-son"

interaction.

Tiberius was

hardly Caesar's first choice to succeed him. The main

reason that Tiberius stood at the end of the line was that he had no

shared blood with Augustus Caesar. Since his mother Livia

was from the "Claudian" family, Tiberius was also a Claudian.

Augustus was from the "Julian" family.

One reason Julius Caesar had selected Augustus as his heir was

due to the shared family blood. Now Augustus was

determined to find a "Julian heir" as well.

Since Tiberius was

not part of the "Julian" bloodline, he wasn't even on the radar.

However, in 14 AD upon the death of Augustus,

77, Tiberius Claudius Nero was the

last man standing in a long and tumultuous line of fallen potential

heirs.

|

|

The Early Years of

Tiberius

Augustus Caesar

was a remarkable politician, but it is widely agreed that he was

largely responsible for the most dysfunctional family in Rome as

well.

In 38 BC, Octavian

(Augustus) divorced Scribonia, an older woman whom

he had married because of her family ties to Pompey back in the

time when he needed Pompey's political support. It is said

that Scribonia gave birth to Octavian's only child, Julia,

on the same day as their divorce.

Octavian then “persuaded” Tiberius Claudius Nero, the father of

Tiberius, to divorce his young wife Livia so she

could marry him. Mind you, Livia was pregnant with another

son (Drusus) at the time. Octavian and Livia were married

immediately after both divorces. Octavian was from the

Julian line. Livia was from the Claudian line. Their

marriage marked the first combination of the "Julio-Claudian

Line".

After the divorce, Julia went to live with

her father Octavian, while Livia's two sons lived with their father for

five years until his death in 33 BCE. After that Tiberius

and his brother Drusus were raised by their mother Livia and

Octavian.

Once the two boys

moved into the home of Livia and their stepfather Octavian, Tiberius and his brother Drusus

bonded together against the world. Four years apart in

age, they became inseparable. They were each other's

best friends.

Tiberius was 4

when his mother married Octavian. As he grew old enough to

understand, he realized that Octavian was directly responsible

his parent's divorce. Not surprisingly, Tiberius was never

fond of his stepfather.

Although Tiberius always carried some lingering animosity

towards his famous stepfather, his youth was normal (if you can

call growing up in the Imperial Palace 'normal'). Tiberius

was well-educated. He

was described as intelligent and thoughtful. Since

Tiberius had little interest in entering politics,

like most patrician youth, he was put into the military.

Tiberius served well. Since the thought of becoming

Emperor was too far-fetched, Tiberius concentrated completely on

his military career. Tiberius became an exceptional military general.

Tiberius was also very happily married.

As you will

discover, in the latter part of his life, Tiberius turned into a

monster who executed people right and left and indulged in

astonishing sexual depravity. Unlike Caligula, who was a

monster from practically his first breath, when you study the

early life of Tiberius, there was

absolutely no hint that someday Tiberius would turn dark.

Something changed this man.

Marcus Agrippa

Augustus Caesar, or

Octavian as

he was known in his youth, was the grandson of Julius Caesar's

sister Julia Caesaris. Considering that

Roman had the most powerful military ethic since Sparta, it is kind of ironic that Rome's greatest ruler grew

up as something of a nerd. Octavian was a sickly weakling who never excelled

at hand to hand combat or showed much interest in military

matters. In a world that valued fierce warriors over

intellectuals, the greatest leader of Rome turned out to be the kid

who had his nose stuck in a book all the time.

Julius Caesar on the other hand was both a warrior and a

political genius.

While others despaired that the weakling Octavian had no

future in the military, fortunately Julius Caesar recognized the young man had talents

that no one else seemed to notice. He based his secret

decision to name Octavian his successor on his hunch that

Octavian was indeed special. Caesar kept his cards

close to his chest. Octavian

himself, just a teenager at the time, didn't even know what his

famous uncle thought of him. Upon the murder of Caesar, the news that he was

named in the will to be

Julius Caesar's successor was just as surprising to him as it

was to

everyone else.

Although

Augustus Caesar was never much of a general, he didn't need

to be because his best friend Marcus Agrippa was a brilliant commander.

Upon Julius Caesar's death, Octavian was forced to fight a

long series of civil wars to eliminate all of his enemies,

including of course Mark Antony and

Cleopatra. Agrippa was the man who won all the battles such as

Actium

that resulted in Augustus Caesar becoming the sole ruler of

Rome. After the military campaigns were over, Agrippa

helped Augustus run the government. Agrippa was responsible for improving many public works in the

City of Rome. Agrippa was Caesar's trusted right-hand man.

There was an incredible bond between these

two men. They were best friends. Augustus knew

beyond a shadow of a doubt that Agrippa would be a terrific successor.

But Agrippa had no "Julian Blood" in

him. What to do?

|

|

|

Julia,

Guardian of the Julian Bloodline

One of the major

problems Augustus faced was how to ensure an orderly succession

after his death to the new form of power he had created.

Augustus wanted to make sure there would be no repeat of the

endless rounds of civil wars when he died. In the absence of sons, Augustus used the time-honored Roman

strategies of adoption and controlling the marriages of the

women in his family, in particular his daughter Julia.

From his actions, it is clear that his aim was to secure a blood

relative - preferably a direct descendant in the Julian line - as

his successor. Despite all of Augustus' efforts, it is one

of the greatest ironies of history that his strategy ultimately

resulted in the Emperor Caligula, hardly the kind

of ruler Augustus had envisioned.

Tiberius,

as the oldest son in the Imperial Family, had a legitimate

claim as the successor to Augustus. However, Tiberius

was from the Claudian line and had no "Julian blood" in him.

Thanks to Augustus' eternal preoccupation with the Julian

bloodline, Tiberius fell out of consideration.

Tiberius had long known that Augustus wanted Marcus

Agrippa to

succeed him. And with good reason. The two men had been through a lot of battles together. However,

like Tiberius, Agrippa did not have a single drop of "Julian

blood" in him either. Giving the problem serious

thought, Augustus thought of a solution.

To cement their close ties, Augustus Caesar asked Agrippa to

marry his only natural child, daughter Julia (from

his first marriage). Although Agrippa was 25 years senior

to Julia,

the union was successful. They had five children

together. Augustus was thrilled. Since

Augustus

and Agrippa were the same age, the plan was that surely one of

the two would live long enough until Agrippa and Julia's

sons came of age. Down the road when one of these

children became Emperor, the Julian bloodline would

continue. The dynasty would stay intact.

|

The Event

that Changed Tiberius' Life

Since Augustus

did not have any personal military skill, he had always

relied on Agrippa. However, at this point in their

careers, Augustus needed

Agrippa to stay in Rome to help manage the affairs of state.

Now Augustus was forced to rely on his extended family to conduct military

campaigns, especially Tiberius and Drusus, the two sons of

his wife Livia. Fortunately, both of his stepsons

turned out to be excellent commanders.

With Augustus

and Agrippa running the state and Drusus and Tiberius

patrolling the borders, Rome reached its absolute zenith of

power.

|

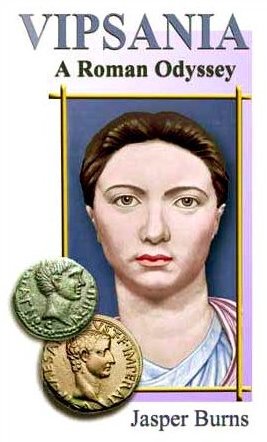

Tiberius had a

very close tie to Agrippa. Tiberius was married to

Vipsania, the daughter of Agrippa by a previous marriage.

By all accounts, Vipsania was the love of Tiberius' life.

They had one child together, Castor.

The event that

changed everything occurred in 12 BC. That is the year

that Agrippa died of natural causes during a military campaign.

He was 51. Now that his first choice to succeed him was

gone, who would Augustus turn to?

Tiberius

was an obvious choice. He had done

well as a military general. He also had a formidable

patron in his corner, his mother. Empress Livia was doing

everything in her power to see that her son be put at the head

of the line of succession. Finally Augustus gave in

to his wife's pressure, but on one condition.

Tiberius had to marry his daughter. Recalling the five babies that Julia had given him during her

marriage to Agrippa, Augustus figured since that move worked once,

why not try it again? A marriage between Tiberius

and his fertile daughter Julia would surely produce more

children. Down the line when Tiberius died, his own

male heir would have Julian blood.

Thus, after the death of

his friend Agrippa, Augustus decided to promote his stepson

Tiberius, believing that this would best serve his own dynastic

interests. In addition, Augustus forced his daughter Julia, just

recently widowed by the death of Agrippa, to marry Tiberius so

that Tiberius could begin producing his own heirs with Julian

blood.

The idea was absurd for all sorts of reasons. Julia was

the stepsister of Tiberius. Julia and Tiberius had

literally grown up in the same household as brother and sister! Although

there were rumors they had once been kissing cousins of a

sort, at this point Tiberius didn't like Julia very much.

Tiberius preferred to keep Vipsania, the wife he already

had.

|

|

Neither Julia nor

Tiberius wanted this Marriage.

Tiberius was happily married with a wonderful wife and a great son.

Furthermore, Vipsania was now pregnant with their

second child. Tiberius was a grown man with his own life.

Through his military career, Tiberius had served Rome well.

He deserved better. Tiberius resented being treated like a

pawn to be pushed around the board. If Augustus wanted him

to be the next Emperor, he would cooperate. However, he

could care less about Augustus' plan to create more "Julian blood".

Tiberius bristled with anger. First Augustus had broken up

the home of his mother and father, now he wanted to do the same

thing to him. This decision was thoroughly

repugnant.

Furthermore, Tiberius disliked Julia. Besides having the warmest attachment to Vipsania,

Tiberius was

disgusted with the conduct of Julia, who had made indecent

advances to him during the lifetime of her former husband

Agrippa.

Her advances towards him confirmed the likely truth of the

strong rumors that she regularly cheated on her aging husband

Agrippa. Fully aware of her reputation, Tiberius was

leery. Who wants a woman like this as a wife?

|

The knowledge that

Julia was a woman of loose character was well-known

throughout Rome. Julia's behavior while married

to the respectable Agrippa had been scandalous public

knowledge. Nor did Julia even bother to deny it.

Julia treated her affairs like a running joke. Once a

woman who knew about Julia's shocking behavior noticed that

for someone who distributed her favors so wildly, how did

she manage to always give birth to sons who strongly

resembled her husband Agrippa? Julia replied, "I

never take on a new passenger unless the ship is already

full."

This

was just one of many eye-raising stories. Julia was a

complex woman. Julia had many good qualities.

Her love of literature and culture plus her

considerable wit made her a pleasant and stimulating

companion. Her kindness and utter

freedom from vindictiveness in a society that had so little

of these qualities had won her immense popularity. The

people who knew about her faults were amazed that she

combined them with qualities so much their opposite.

Despite

her good qualities, make no mistake about it - Julia had a

serious dark side. This impending marriage to Tiberius made

Julia deeply unhappy.

From Julia's point of view, she was sick and tired of being told

whom to marry by her father. This marked the third time

that Augustus had dictated to Julia which man she would marry.

Did she not have a right to a life of her own? Thanks

to the death of Agrippa, a man twice her age, Julia had begun to pursue men she found attractive with a

clear conscience for a change. Julia already

had someone else in mind and it certainly wasn't her gloomy

stepbrother. Julia had done her duty. She had

married for political reasons twice. She had produced

three male heirs. Now she was ready to have to some fun!

|

Tiberius was

aghast. Why couldn't Caesar see that he was happily married?

His wife Vipsania was currently pregnant with their second

child. Political marriages were common in Rome, but

Tiberius wasn't really that interested in climbing higher.

That removed the only plausible reason he might have to

willingly divorce Agrippa's daughter Vipsania to marry

Agrippa's widow Julia. Right up to the last moment,

Tiberius pleaded with his mother Livia to persuade Augustus to

change his mind. Augustus would not relent. He was determined to

have his way.

Julia and Tiberius

had no choice in the matter. Based on Roman Law, Augustus had the right

to force the marriage. Therefore, against his will, Tiberius was forced to divorce Vipsania

Agrippina, the

woman he dearly loved, and marry Julia, a woman said to be the

biggest whore in all of Rome.

|

The

Doomed Marriage

The marriage was

thus blighted almost from the start. At first, Tiberius

did the best he could to live quietly with Julia and make

the best of it.

However, it didn't take long until Julia rebelled against

her father and took her anger out on Tiberius. A

rupture soon ensued which became violent.

After the loss

of their son, who was born at Aquileia and died in infancy,

Tiberius screamed he would never sleep with Julia again.

Now there was much infidelity and it wasn't discrete either.

In 6 BC, six years

after their 12 BC wedding, the couple

separated for good. The union had produced no heirs, no Julian blood

and much bad will throughout the entire Imperial family.

|

Aftermath - Julia

Julia's life was

never the same. After Tiberius left, she continued her life as a sexual

profligate, entering into numerous scandalous affairs.

In fact, in 2 BC, just four years after the split, Julia's

rampant affairs had become such a huge

embarrassment to her father Augustus that he couldn't stand it any

more.

The final straw

was Julia's affair with Antonius, the son of Mark

Antony. Mark Antony, you may remember, is the man who

expected to rule Rome after the death of Julius Caesar only to

be upstaged by a weakling teenager known as Octavian.

Antony and Octavian became deeply bitter rivals. It took

fourteen years, but Octavian chased Anthony across the earth

till finally his greatest rival met his death in Egypt.

You don't suppose the son of Mark Antony lusted for revenge

against the man who killed his father?

When news of Julia's affair with the son of Augustus' greatest

rival made its way to Augustus, this time Julia had crossed the

line. In addition to her copious promiscuity, there was a

strong hint that Julia had allowed herself to be used as a way

for conspirators to get close enough to Augustus to assassinate

him. Antonius was

sentenced to death for treason. Julia was exiled to a

barren

island with no men! Julia would never return to Rome.

Nor was she able to reconcile with her father. She

remained an outcast for the rest of her life.

Julia's entire

story is actually very tragic. Julia died a

rebellious little girl who was willful and passionate on the one

hand, but always carried a gentleness and compassion for the

people of Rome. During her life, she was dearly beloved by

nearly everyone she met except her stepmother, Livia, mother of

Tiberius. Although Julia did have a sharp tongue for her

father, she was also said to be his favorite companion.

Julia was loyal to her father throughout her life until the

marriage to Tiberius broke her completely.

The decision by

Augustus to exile his daughter was a mockery. Yes,

Antonius may have hoped to get close to Augustus via Julia, but

Julia was hardly intent on betraying her father's safety. Even though her

affair with Antonius raised eyebrows, there was no proof that

Julia was disloyal to her father. More than likely, she

chose this man as a way to hurt her father's pride, not to

cooperate with any plot.

Ultimately,

Augustus had no one to blame but himself for his only daughter's

miserable end. He ruined her life.

Aftermath -

Tiberius

After he separated

from his wife Julia, in 6 BC, Tiberius departed for Rhodes,

an island near Turkey. He wanted to get as far away from

Rome as possible! The promiscuous, and very public,

behavior of his unhappily married wife Julia was the likely

reason for the departure. The writer Tacitus

calls Julia's behavior Tiberius'

intima causa, i.e. his innermost reason for departing

for Rhodes. Tacitus seems to ascribe Tiberius' move to a

combined hatred of Julia as well as his continued longing for

Vipsania that was driving him crazy with remorse. Tiberius

had a good thing and he had lost it.

Vipsania had moved

on after her divorce from Tiberius. Vipsania was realistic

about what had happened. She was hurt of

course, but understood the divorce was definitely not Tiberius'

fault. It wasn't her fault either. Why sit

around and feel sorry for herself? Vipsania landed

on her feet. She was still young and quite

attractive. One year after the divorce, she had

married a powerful Senator named Gallus.

Tiberius had long

hated this man with a passion. During his marriage to

Vipsania, Tiberius had been away from Rome for long periods of

time keeping the borders in Germany safe from marauding

barbarians. There was a strong rumor that Castor,

Tiberius' son by Vipsania, was in fact the child of Gallus. Complicating matters,

Gallus never denied

his paternity of Castor. This unsettling thought had long

lingered in the mind of Tiberius as well as the possibility

Gallus was also the father of the child Vipsania was

expecting on her divorce. Tiberius brooded that Vipsania

had preferred Gallus to him even while they were married.

He wondered if Vipsania had even secretly approached Augustus to

suggest she had no objections to divorcing Tiberius.

Nothing preys upon

a man's mind more than worries about an unfaithful wife that he

cares about. A cursory look at the circumstances suggests

that Tiberius had a lot to worry about.

After Gallus married Vipsania, they had six children together.

It didn't Tiberius' mood much to know his former

wife's new marriage was a happy one that was producing one child

after another.

Tiberius on the other hand had moved on to a bitter marriage

with an unfaithful woman that had produced no heirs and much spite.

Look what she had. Look what he had. The unfairness of it all drove him crazy.

When Tiberius

could not bear the pain anymore, the thought crossed his fragile mind

that perhaps Vipsania would consider seeing him again.

As previously

mentioned, political marriages were common in Rome among the

upper class. However, these often business-like

marriages involved human beings with real feelings, not

robots.

The pursuit of love is not an instinct that can be turned on

and off at will. Adultery was the safety valve that

allowed these frequently loveless marriages to survive.

It was an imperfect solution, yet a convenient one we still see in our

modern society.

When his

marriage to Julia began to hit the rocks, a forlorn Tiberius

sought out his former wife Vipsania for solace. He

still loved her deeply and felt the deepest regret for

divorcing her. Now he desperately wanted to take her

in his arms again and regain the warmth they had once

shared.

Vipsania was

sympathetic to Tiberius' plight, but unwilling to take any

sort of risk. Despite his tears and his pleading, Vipsania

kept Tiberius at arm's length lest she endanger herself and

her children by her new marriage. She did not wish to

face the wrath of Augustus or her husband.

|

|

Vipsania was a

sensible woman who knew that no possible good could come from

renewing her relationship with Tiberius. She had a good

marriage and had no desire to bring danger by flirting with this

deeply troubled man. Who in their right mind chances

incurring the wrath of the Imperial Family? Besides, Tiberius was

out of his mind thinking she was still interested in him.

No good could ever come of this, only misery and danger.

Vipsania quietly

reported the meeting to someone who passed the information on to

the Imperial Family. When Augustus found out about this

dangerous meeting, he made sure that Tiberius would never be

allowed to come near Vipsania again.

Tiberius was forbidden to ever see Vipsania again.

The threat was unnecessary. Vipsania's cold shoulder had

already closed the door to that dream. Tiberius knew there

was no hope of regaining the woman that he loved. He found himself locked into a marriage to a woman he loathed, a

woman who

publicly humiliated him with nighttime escapades in the Forum,

with no back door escape possible. He would never again be able to see the woman he really

loved, a woman who had married his most bitter rival. Thanks to

the meddling of Augustus, Tiberius was stuck with Julia

whether he liked it or not.

They say that Tiberius was prone to depression and melancholy.

Well, in this situation, he appeared to have a good reason to

suffer. It couldn't be easy knowing that his former wife,

the woman he would love till he died, was perfectly happy

resting in the

arms of a man he hated and bearing his children.

Jealousy and bitterness ate at Tiberius. It dominated his

every thought. It made him sick. It produced the

kind of pain that leads to madness.

Escape to the Island of

Rhodes

Once the loveless

marriage collapsed, Tiberius' life was never the same.

Tiberius was

bitter enough towards Julia, but his hatred towards Augustus for

breaking up his happy marriage to Vipsania was thinly concealed.

Thanks to his bitterness, Tiberius could not have cared less

about becoming Emperor. He hated Augustus, he hated Rome,

and he hated the world. Hit the Rhodes, Jack, and don't

come back.

Tiberius' decision

to move to

Rhodes was not received well. If Augustus was to die

tomorrow, Tiberius was supposed to step in on a moment's notice.

What gave him the right to go live on an island that was at best a

two week journey away? It would take two weeks to

send him any news and two weeks for him to get back to Rome.

This would not work.

Let's face it, Tiberius was

rebelling against Augustus Caesar just as Julia had

rebelled against him.

Oddly enough, just

as Tiberius was ready to sail, Augustus fell very ill. Somewhat

apocryphal stories tell of Augustus pleading with Tiberius to

stay, even going so far as to stage this illness. Tiberius's response was to anchor off the shore of Ostia, the

port of Rome, until

word came that Augustus had survived. At that moment,

Tiberius

set sail straightway

for Rhodes.

Tiberius's

withdrawal from Roman life was disastrous for Augustus's

succession plans. Augustus, now 57 years old, was left with no

immediate successor. There was no longer a guarantee of a

peaceful transfer of power after Augustus's death, nor a

guarantee that his family, and therefore his family's allies,

would continue to hold power should he die.

Augustus was

furious. How dare his stepson snub him! Tiberius

was openly rebelling against the role that had been chosen for

him. Now Augustus became bitter towards Tiberius.

A serious grudge developed between the two men.

Once Tiberius

made it to Rhodes and gave it some thought, he suddenly realized his own life was in danger for spurning

Augustus. He reportedly discovered the error of his ways and requested to

return to Rome several times, but each time Augustus refused his

requests. Augustus referred to him as "The Exile".

Augustus had to develop a new plan of succession. Fortunately for Augustus, his disgraced daughter

Julia had produced three male heirs by her marriage to Agrippa.

As of 6 BC, one boy was 14, another was 11. If Augustus could live long enough, one of these boys would

become old enough to take his place. That became the new

plan of succession.

Except there was

one problem. Two of the boys died mysteriously and the

third was sent into exile thanks to a sex scandal. In a

flash, three legitimate heirs to the throne had gone poof!

If we can hit

the "Pause" button for a moment, doesn't it strike you as

curious that during the reign of Augustus so many people

died or got exiled? People died around Augustus all the time;

I just haven't reported them all. You think this is a

long story? If I explained the story of every person around the

Imperial family that died in these days, this epic saga would

never end. Rome was a very dangerous place to be. In

fact, there are several more deaths just down the road as

well. There is a fascinating story operating behind

the scenes here. It is a tale we shall save for later.

The Return of

Tiberius

Now that the last

three direct heirs with "Julian blood" in them had been eliminated,

that

left Tiberius as the last man standing. Augustus was fit

to be tied. There was no one else qualified to become Emperor

except his ungrateful and dour stepson. Ten years after Tiberius

had sailed off for Rhodes, he was recalled to Rome. In 4 AD, with great reluctance,

Augustus called Tiberius out of retirement and officially

recognized him as his successor, adding the words 'This I

do for reasons of state.'

There passed ten

more years of sullen resentment between the two men.

When Augustus passed away in 14 AD, he relinquished his power to

a man he deeply disliked and didn't trust. Augustus knew full well that Tiberius hated him for

ruining his life.

Actually, Tiberius wasn't the only person whose life was ruined

by Augustus. There was Julia too.

For that matter, every person

involved in Julius Caesar's assassination had to die for

Augustus to become Emperor. Then Mark Antony and Cleopatra

had to die for Augustus to become Emperor. Then Julius Caesar's son Caesarean by Cleopatra had to die

for Augustus to become Emperor. In fact, by some accounts,

Augustus had to fight as many as 30 different civil wars to rid

himself of every one of his enemies. It is said that

Augustus' ascension to the throne ended 100 years of Roman Civil

Wars!

Countless thousands of people died during Augustus' climb to the

top.... All that bloodshed just so Augustus could hand over his hard-earned title

to a bitter stepson who hated his guts and didn't want anything

to do with the damned throne. All that wasted energy

over Julian blood. For what? Augustus died knowing his

successor was next to worthless and he had no one

to blame but himself.

Such irony.

|

Tiberius

Takes Over

In 14 AD, at the

age of 56, Tiberius reluctantly ascended to Imperial power. The continuation and success of the newly

created Empire rested squarely on the shoulders of a man who

seemingly had only a partial interest in his own personal

participation.

Tiberius would rule for 24 years. His reign is divided by

historians into two equal parts. For the first twelve

years, by all accounts, Tiberius was an

unenthusiastic but competent ruler. Although an extremely

efficient emperor, especially in the provinces, Tiberius was

never popular either with the senators or with the populace. He

had a grim personality and difficulty in expressing his wishes

clearly to the Senate. Put another way, his powers of

persuasion were limited. He considered the Senate a den of

fools and they didn't have much good to say about him either.

While Augustus had been the perfect political tactician with a

powerful personality yet approachable demeanor, Tiberius was a

direct contrast. His relationship with the Senate was always

contentious. He was a dark figure, keenly intelligent,

sometimes terribly cunning and ruthless, yet basically miserable

at being forced to assume the role as Emperor. Tiberius was

given to bouts of severe depression and dark moods that had a

great impact on his political career as well as his personal

relationships.

His reign abounds in contradictions. Despite his intelligence,

he allowed himself to come under the influence of unscrupulous

men who ruined Rome while he turned a blind eye.

Furthermore, despite his vast military experience, he oversaw

the conquest of no new region for the empire. He was

content to simply defend the borders of existing territory.

Tiberius had the ability, but halfway through his reign he

stopped using it. A casual observer would speculate that

he simply burned out.

There were two

extremely suspicious events that took place during Tiberius'

reign. Tiberius had two excellent men in line to be his

heir. One was Germanicus, Tiberius' nephew. Germanicus

was the only son of Tiberius's beloved brother Drusus.

Tiberius and Drusus were incredibly close growing up. Tiberius'

nephew Germanicus

grew up to become a gifted military leader who was extremely

popular. As the nephew of Tiberius, Germanicus was widely

heralded as the Crown Prince of Rome. It was said that the

people of Rome said prayers that Tiberius would hurry up and die

just so Germanicus could take over.

Germanicus was

married to Agrippina, the daughter of Tiberius'

much-disliked wife Julia from her previous marriage to Agrippa.

That meant that all of Germanicus' children would carry "Julian

blood" because their grandmother Julia was the daughter of

Augustus. From the very start, Germanicus was outgoing,

athletic, and brilliant. Augustus was so taken with the lad that he seriously considered

promoting him to be his successor even though Germanicus was 23

years younger than his uncle Tiberius. Augustus was

persuaded by his wife the Empress Livia to stick with the more experienced

Tiberius, but in so doing Augustus at least insisted that Tiberius name Germanicus as his successor.

Germanicus would help restore the missing Julian bloodline to

the throne. Tiberius agreed to carry out Augustus' wishes,

however a tragedy intervened.

In 19 AD, just five years into

the reign of Tiberius, during a military campaign in Turkey, Germanicus turned up dead by poisoning.

The news of Germanicus's death was received at Rome with

universal lamentation; people took his death the same way modern

Americans responded to JFK's assassination. All ranks of the people entertained

an opinion, that, had Germanicus survived to succeed Tiberius, he would have

restored the freedom of the Republic.

All eyes

in Rome turned towards Tiberius in suspicion because the

suspected assassin was a well-known friend of Tiberius.

Piso,

the man suspected of carrying out the assassination, was put on

trial. In the middle of the trial, Piso mysteriously

killed himself to avoid telling the truth. Conspiracy

theories abounded. Many believed Tiberius may have had Piso

murdered before he could implicate the emperor in Germanicus'

death. It was said that Tiberius was jealous of his

popular nephew and the fear of his nephew's increasing power

was the true motive behind the conspiracy. The suspicious

death of Germanicus greatly affected Tiberius' popularity in

Rome.

|

|

Unfortunately,

unless there are details I am missing, blaming Tiberius doesn't make a

lot of sense. No matter how popular Germanicus was, he was not a serious threat to his uncle

Tiberius. Far from it! There is no evidence of

public discord between Tiberius and his uncle.

Furthermore, Tiberius seemed to be more interested in giving his

job away than he was murdering his only nephew to protect his

position. Tiberius' attitude was, "You want my job?

Here, you can have it!"

Maybe the

unfairness of the accusations explains why Tiberius

was so bitter that people would blame him. Tiberius

was never the most cheerful guy to begin with. This

incident was the beginning of the end. He began to brood

over the accusations. Tiberius

seems to have tired of politics at this point. Three years

after the death of Germanicus, in AD 22, Tiberius

began to share his authority with his natural son Castor, 35.

Castor, you may remember, was his only son by his marriage to Vipsania.

Although Tiberius wasn't close to Castor, secretly suspecting he

might not even be the boy's true father, he was at least willing

to groom the young man to take his place.

It was at this point that Tiberius began making yearly

excursions to Campania that reportedly became longer and longer

every year. Then came the final tragedy. In AD 23, Tiberius' son

Castor mysteriously died, a

likely victim of poisoning. First Germanicus, now

Castor.

People sure have a funny way of dying around here.

The loss of his

son Castor was the straw that broke the camel's back.

At this point, Tiberius seemed to lose all remaining

interest in ruling Rome. No one in Rome liked him and

there was no one in Rome he liked either. He hated his

job and he hated his life. Tiberius had been going

through the motions for some time.

In AD 26, Tiberius

retired from Rome altogether and moved to the island of

Capri. History would not judge this move kindly. Tiberius

has received scathing criticism for abandoning the state for

the final twelve years of his reign. His withdrawal from public

life would prove disastrous.

His susceptibility to the scheming of those around him made Rome

vulnerable to tyranny.

By his actions, Tiberius basically

said, "Take this job and shove it. Let Rome be damned."

Because he had probably always been happiest when away from the

capital and its endless deaths and constant plots and intrigue, Rome's emperor

simply departed to Villa Jovis, his holiday mansion on the isle of Capri.

Tiberius left a

man named Sejanus in charge of running the

Empire. Tiberius had just made a stunning mistake.

He handed the keys to the most unscrupulous man in Rome, someone who would

stop at nothing to get whatever he wanted.

The Emperor had just asked the

Fox to guard the henhouse!

|

|

|

|

4 Sejanus - The Man Who

Barely Missed Becoming King

Beware the Man

who promises to protect you. He will protect you from

every Man but himself.

It probably

should come as no surprise, but Ancient History

was one of my favorite courses back in high school. I

definitely paid attention in that class and I can assure you

that the name "Sejanus" was never mentioned.

And yet this monster came within a stone's throw of stealing

the throne right out from under Tiberius' nose. It was

that close!

The sordid tale of

Lucius Aelius

Sejanus is likely to be one of the best stories

you have never heard before.

|

Sejanus was

the son of Tiberius' first Praetorian Prefect Strabo.

Thanks to his father's position, Sejanus was an

equestrian by birth, one step below the patrician class.

Strabo had previously served under Augustus. As a boy, Sejanus

grown up alongside the

Imperial family thanks to the unique

body guard responsibilities of his father during the Reign

of Augustus.

In 16 AD, 2 years after Tiberius took

over, he appointed Strabo to the governorship of Egypt (the

highest political position for an Equestrian of the time). That created an opening

for the head of Rome's Praetorian Guard. Sejanus was

about 20 at the time; Tiberius was 58. Tiberius had

known Sejanus since he was a child. Despite his

youth, Tiberius felt comfortable giving the young man his

father's job. After all, Sejanus had spent his entire

life surrounded by the affairs of the Praetorian Guard.

Everyone knew him. Sejanus moved fluidly into the same command of the Praetorian

Guard that his father had just vacated.

Sejanus was young, but very confident. Some would say

'cocky'. Sejanus possessed an ambition that knew no

bounds.

Sejanus

quickly became one of Tiberius' closest confidants and

trusted advisors. It didn't take Sejanus long to expand his

responsibilities to other areas as well. Over the next few years, Sejanus

impressed Tiberius through his gift as a sycophant and

through his many administrative

abilities. The young Prefect continued to be entrusted

with more duties and more power.

Sejanus had reached a level of importance that was oddly out

of balance with his secondary station in life. He had

seen an opportunity and run with it.

|

His close relationship

with Tiberius put him at odds with other members of the

Imperial family, in particular the emperor's son,

Castor, 29.

After Germanicus, Castor was next in line to inherit the

throne. Castor was keenly ambitious himself and

therefore highly sensitive to any threat to his position. He

kept close tabs on the movements of this overly ambitious

upstart who was clearly doing his best to worm his way into Tiberius' good graces.

As well

Castor should! His instincts were absolutely dead on.

The higher Sejanus rose in government, the more determined

he became to take it all the way to the top. Sejanus wasn't backing down

from

anyone. The two Alpha males developed a serious dislike for

each other. Once in the course of a casual argument

with Sejanus, Castor raised his fist and struck him in the

face. Thanks to Castor' position as son of the

Emperor, Sejanus did not dare strike back. However,

Sejanus was determined to even the score.

|

The tragic

death of the popular Germanicus in 19 AD ratcheted up the

tension between these two rivals. By law, only a

patrician could become Emperor. As an equestrian by

birth, Sejanus should have been out of the running. No

matter. Sejanus was already in the process of

positioning himself as a potential heir. He figured

that with Germanicus dead, Castor was

the most serious obstacle who stood in his way of his climb

to the throne.

Sejanus drew a target on his rival's back, then began to

brew the poison.

The Seduction

of Livilla

Sejanus had a plan. If he could marry into the

Imperial family, his equestrian birth would no longer be an

issue. Sejanus had just the right person in mind -

Castor's wife!

It wasn't difficult to

be interested in the woman. By

all accounts, Livilla was one of the most

tempting women in all of Rome. In addition to her

beauty, Livilla was highly placed in the Imperial family.

Livilla's mother Antonia was the widow of

Drusus, Tiberius' beloved brother who had died

during a military campaign. That made Tiberius

brother in law to Antonia. Her daughter Livilla

was now married to Castor, Tiberius' only

child. A highly respected woman, Antonia was one of

the few people remaining who had stayed on Tiberius' good

side all these years.

Unfortunately, Livilla did not take after her classy mother.

She was described as spiteful, cruel, vindictive and

treacherous. Livilla was not only Tiberius' niece, she

was also his daughter-in-law. Throughout her life,

whatever Livilla wanted, Livilla got.

Sejanus had every opportunity

to chase Livilla. Due to his unique

position, he had the run of the palace. He could be

there at all hours and never raise suspicion. He even

had his own quarters. Ever better, his rival Castor

was usually gone!

Like his

father Tiberius, Castor had been groomed to be a military

leader. Thus Castor was frequently out in the field

for long periods of time commanding troops.

|

|

Furthermore,

Castor was no Prince Charming. He was said to be a

brute with a violent temper. He liked to drink, he

liked to fight, he liked to visit the brothels. His

loutish behavior left the left the door wide open for the

ambitious Sejanus to pursue his wife.

As you can imagine, when Sejanus came knocking, Livilla

didn't put up much of a fight. They began a passionate

affair.

Their affair

was known to no one, but it grew so serious that Sejanus was

actually the true

father of Livilla's youngest son Gemellus, not Castor.

People had

already noticed

the boy didn't exactly take after his father.

Apparently this was a common sport in the highly promiscuous

climate of ancient Rome - let's guess

who the real father is! The casual speculation was a

matter of great concern to Sejanus and Livilla. Not

surprisingly, they were terrified their affair would be

exposed. What if Castor became suspicious?

Sejanus could easily be put to death for his adultery.

After all, this was the Emperor's son that Sejanus had

cuckolded!

It was

unlikely the old goat Tiberius would grant Livilla a divorce

to marry Sejanus. Desperate to be together, but

increasingly scared of being caught, Sejanus and Livilla

hatched a plot. They would poison Castor to death.

This would free Livilla to marry Sejanus, the man she loved.

Using slow

acting poison, his symptoms were chalked off to alcohol

abuse, having as he did the reputation for

heavy drinking. Indeed, the murder was

done so skillfully that the death of Castor in 23 AD gave

rise to no suspicion. The ladder was clear to start

climbing faster.

Whispers in

the Dark

With the major

heir to the throne gone, the road to

the top was free of the most important obstacle.

Now there is just one more hurdle to cross. Sejanus

had to join the Imperial family. In 25 AD, Sejanus

asked Tiberius for Livilla’s hand in marriage. To his

dismay, Tiberius said no. Tiberius knew full well that

Sejanus was engaged in serious social climbing.

Sejanus was still just an equestrian while Livilla was a

member of a noble family of the highest order.

Sejanus

was stunned by the rejection. A marriage to Livilla

would have This was a very serious setback.

Still, Sejanus had the sense not to challenge Tiberius.

He backed down gracefully and bided his time. Despite this

setback with Livilla, Sejanus still believed himself a

potential successor of the emperor. He just had to try

a different route. Sejanus

had a dirty trick up his sleeve.

For years now,

Sejanus had systematically wormed his way in his master's

favor through a combination of praise and the ability to

tell the man what he wanted to hear. Along the way,

Sejanus learned that Tiberius was so insecure that he

overreacted to any criticism and any threat. Sejanus

discovered the easiest way to manipulate his boss was to play

upon the aging man's fears. Any time he wanted a

promotion, all Sejanus had to do was think of a plot to

scare the man to death.

|

After his

request to marry Livilla was shot down, Sejanus stepped up

his whispering

campaign about all the treacherous plots against Tiberius.

Thanks to Sejanus' tales, Tiberius saw an assassin in every

corner and every shadow.

As head

of security, Sejanus could make up all manner of stories.

The more afraid Tiberius became, the more he avoided people.

He had become a hermit in his own palace. That forced him to

rely on others to give him information. Since he had

few friends left he could trust, this put Tiberius in

an awkward position. Sejanus controlled total access

to Tiberius. No one said a word to Tiberius without

first clearing it with Sejanus. Consequently, there

was no one to contradict whatever Sejanus had to say.

Tiberius had become totally dependent on the word of his

trusted advisor.

Preying on a weary old

man, thanks to Sejanus' clever power of suggestion, Tiberius

developed a serious paranoia. As well he should!

The easiest lie to swallow always contains enough truth in

it to make it seem real. For years now, all sorts of

people around Augustus had a way of dying young.

Now with the suspicious death of first Germanicus, then

Castor, the death plague had come to visit the House of

Tiberius as well. Tiberius began to fear for his life.

|

|

|

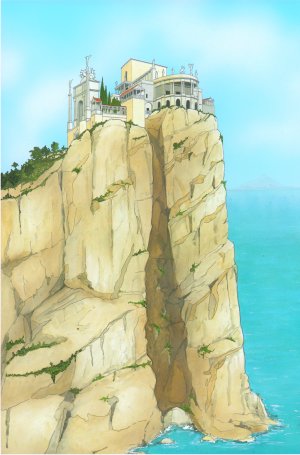

Sejanus

suggested Tiberius begin to think about leaving Rome for Capri

for his own safety.

High

above the Mediterranean Sea in his magnificent mountain

palace, Tiberius would be far removed from danger.

Tiberius could relax and

let his vigorous young assistant handle the daily affairs of

state. Tiberius was 66 years old. He had been

deeply weary of his job for a long time. Now, thanks

to the evil of Sejanus and his lies, Tiberius was scared out

of his wits.

This

promise of escape to his mountain lair was too tempting to

resist. Tiberius took the bait. In 26 AD he made

an abrupt move to Capri. Sejanus had him so convinced

that everyone was out to get him, Tiberius surrounded his

villa with guards and kept an escape boat at the foot of the

cliffs of Capri at all times.

Tiberius left the government in the hands of Sejanus, his Praetorian

Prefect. Sejanus had played his cards as well as

humanly possible. Full of tremendous ambition, with Tiberius

gone, Sejanus had become the de facto

emperor of Rome. He, not Tiberius, was making the day

to day decisions regarding the government of Rome and the

Empire.

In 26

AD, using the Praetorian Guard to do his bidding, Sejanus

began his reign of terror.

Sejanus immediate began to shape Rome to his liking. He used his power to remove any

other possible candidates to the throne. Even though

Castor was gone, Sejanus had a little more housecleaning to

do. Although they were just kids, there was a trio of

potential heirs floating around. Sejanus also began to

round up all political enemies. Using trumped up

charges under the Treason Law, he murdered these men and

stole their estates in the process.

Fear spread through Rome like

wildfire. No one - nobility or peasant - was safe if

they had something Sejanus wanted.

|

Sejanus and

his Mafia, The Praetorian

Guard

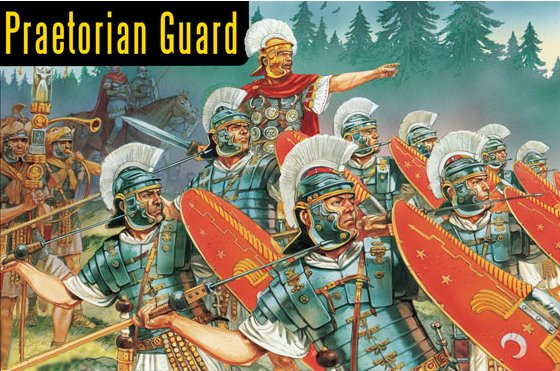

The

Praetorian Guard was a force of bodyguards used by

Roman Emperors, similar to our own Secret Service. It

had been a habit of Roman generals to choose from the ranks

a private force of soldiers to act as guards of the tent or

the person. When Augustus became the first ruler of

the Roman Empire in 27 BC, he decided such a formation was

useful not only on the battlefield but in politics also.

It is quite likely the senseless death of his uncle Julius

Caesar had taught him the need to have protection at all

times. Thus, from the ranks of the legions throughout

the provinces, Augustus recruited the Praetorian Guard.

The Praetorian Guard came to be a vital force in the power

politics of Rome. While Augustus understood the need to have

a protector in the maelstrom of Rome, he was careful to

uphold the Republican veneer of his regime and not let the

presence of the Praetorians become too overbearing. Thus

Augustus allowed only nine cohorts to be formed, 1,000 men

each. Only three cohorts were kept on duty at any

given time in the capital. While they patrolled

inconspicuously in the palace and major buildings, the

others were stationed in the towns surrounding Rome; no

threats were possible from these individual cohorts.

Under

Augustus, the Praetorian Guard had been a benign police

force. By keeping the cohorts totally separate, if one cohort got out of

line, the other eight were prepared to quell any rogue

action.

However, in a

clever move, Sejanus had given the Praetorians real power. In 23 AD, Sejanus convinced Tiberius to have

the the fort of the Praetorians built just outside of Rome.

Sejanus brought the Guard from the Italian barracks out in

the countryside into Rome itself. Now the cohorts were

together in one convenient spot where Sejanus would have

their combined might at his disposal.

Before Sejanus

turned them loose, the entire Praetorian Guard had been at the disposal of

the emperors. Now the rulers were equally at the

mercy of the Praetorians. Sejanus had succeeding in

bringing his own little army into Rome. The 9,000 members of

the Guard were not stupid. They realized they had

become the true power of Rome. Whoever controlled them

controlled Rome. Like a household robot that suddenly

gains "awareness", thanks to Sejanus, the Praetorian Guard

had become the force to be reckoned with in Roman politics.

Fortunately for Sejanus, he was the ultimate lion tamer.

He made sure to keep his animals on a short leash. The

Praetorian men would do his bidding

While the cat's away... with Tiberius asleep at the wheel

hundreds of miles away at Capri, the coast was clear.

Using Praetorian muscle, Sejanus set about creating a vast

power base for himself. Sejanus turned his men into his own little Mafia

and turned them loose.

The

Shakedown

Racket

After

Tiberius' withdrawal, Sejanus systematically took control of

the government. For five years (26 - 31 AD), he ruled

Rome with an iron fist. Anyone in the Senate who

mounted opposition to Sejanus in any form found themselves

in terrible danger of falling victim to a trumped up charge

of treason.

Sejanus' Reign

of Terror began in 26 AD. However, thanks to Tiberius,

the climate of fear in Rome had begun long before that.

When he

succeeded Augustus, Tiberius started out well enough.

However his thin skin quickly got the better of him.

Unaccustomed to politics and dealing with opposition, the

disagreements with the Senate got to him. Furthermore,

the veritable deluge of public criticism and derision stung

him badly. People compared him to Augustus and found

him wanted. Tiberius was no match for his popular

predecessor, the sunny and witty Augustus. "Dump

Tiberius in the Tiber" soon became the joke of the

day.

Thanks to his

hideous marriage to Julia, his broken love affair with

Vipsania, his bitter quarrels with Augustus, and his long

exile to Rhodes, the mental state of Tiberius had greatly

deteriorated from his days as the confident commander of the

Roman legions in Germany.

Over the

years, Tiberius had grown about as jaded and cynical as they

come. He had developed a grim view of human nature.

Tiberius had always been highly suspicious of the motives of

others, but now in his later years he developed a pathological

paranoia. Everyone was out to get him.

To read the story of Tiberius, it is impossible not to

compare him to our modern day Richard Nixon. "You

won't have Dick Nixon to kick around any more."

Notorious for his own thin skin, Nixon jeopardized his

presidency by his constant overreaction to criticism.

Watergate developed as the direct byproduct of Nixon's

constant use of dirty - and highly illegal - tricks to

sabotage his political enemies. If ever there was a

case for reincarnation, this might be one to look at.

On his departure for Capri, the Emperor said, "You

won't have Tiberius to kick around any more."

Or maybe it is just my imagination he said that.

Tiberius' mean

and vengeful streak led him to strike back against anyone he

suspected of being an enemy. Thanks to the dissent that started

largely with the death of Germanicus, Tiberius began to interpret any insults to the

emperor as tantamount to treason against the state. Hoping to

quell all plots in the bud, Tiberius frequently invoked the

Treason Law against any and all suspicious

behavior. Tiberius encouraged informers to come

forward and name conspirators.

Under the Treason Law, people who informed against an individual

suspected of treason received a portion of the accused's estate

when he had been convicted and executed.

Not surprisingly,

there were always plenty of informers ready to spy on their

neighbors. Tiberius accused Roman men and women of many,

even silly crimes that led to capital punishment and

confiscation of the criminal's estate. Since there was practically no recourse against false

accusations, many innocent people were put to death for the

flimsiest of reasons. Off with their heads!

The

results were predictable. Soon no one in Rome dared

say a negative word. The entire city was miserable and

frightened, but at least the executions tapered off.

|

|

However, once Tiberius was out of the

picture, Sejanus elevated the use of the Treason Law

to an art form. He developed a shakedown technique

that would have made the Mafia proud.

The Law

of Majestas (Treason Law) in the hands of an

unscrupulous person like Sejanus was a terrifying weapon.

The punishment in the time of Tiberius was death (usually by

beheading) and confiscation of property. A traitor to the

state could not make a will or a gift or emancipate a slave.

Furthermore, it did no good to commit suicide before trial.

The death of the accused did not extinguish the charge.

If found guilty of treason of the gravest kind, such as

levying war against the state, the memory of the deceased

became infamous and his property was forfeited as though he

had been convicted in his lifetime.

The Senate had little choice but to cow to the man who

controlled 9,000 Praetorians within the very walls of Rome.

Using his "treason acts", Sejanus could have any man

arrested he wanted to. Many of Rome's leading citizens

were executed in this way. Sejanus would point to a

man and tell the Praetorian Guard to go round him up.

Poof! He was gone. This tyranny terrified all of

Rome.

With this kind

of threat, if Sejanus told you to do something, you did it

or else. There was no way to defy Sejanus. No

one dared cross him.

"It was

only when Tiberius withdrew to Capri that things

changed, especially over the last five or six years of

the reign. Death began replacing deportation, the

activities of professional accusers reach a new peak,

with evidence being extracted by force, fear or fraud."

Crime and Punishment in Ancient Rome by

Richard Bauman

Does Tiberius

Know About This?

Naturally you

say, "Let's tell Tiberius!" Easier said than done.

That's the kind of message that could get you killed.

Talking to Tiberius was tantamount to taking on suicide

mission.

Sejanus made

sure that all mail sent to Tiberius was read ahead of time.

This wouldn't work.

Tiberius was

stranded ten miles offshore on a remote island two hundred

miles from Rome. People communicated with his villa

from land through light signals similar to Morse code.

Are you going to put your message out there for everyone to

see? No.

So you take a

boat and try to sneak out to the island, a sort of commando

operation. That's quite a gamble. You don't

suppose Sejanus' henchman will see you coming?

And even if you sneak onto land at night, you still have to

get through the tight security around the mountaintop villa.

Sounds like a great movie, but unlikely in real life.

If you make an

official visit, you have to clear it through Sejanus.

Practically no one was allowed to visit Tiberius except

friends and family. Even if you get your visit

approved, there is a strong chance your meeting will be

supervised. Thus you better have a compelling backup

line of conversation. And now you are on

Sejanus' watch list. Very risky.

One way to

reach Tiberius would be through the use of a trusted friend,

but he didn't have very many "trusted friends". More

than likely, if you complained to someone important enough

to reach Tiberius, you might easily find yourself

complaining to a member of Sejanus' feared web of spies.

Very risky.

The Imperial

Family back in Rome was a possibility. They were aware

of the climate of fear in Rome, but they were also aware

that Sejanus has them watched like a hawk. Any

suspicious movement would be questioned. They would be

risking their own lives to ask permission to talk to

Tiberius.

Besides, there

is a strong and very scary chance that Tiberius knew what

was going on and approved of it. Or would he even

care?

Thus, by controlling access to Tiberius,

Sejanus guaranteed his total control of

Rome.

Clearing the

Path to the Throne

Enjoying unlimited power in Rome, Sejanus was free to

act.

Sejanus' next step was to remove the two immediate heirs to the throne,

Nero

Caesar and Drusus Caesar, and their

irritating mother Agrippina as well on what were most likely

fictitious charges of treason. These two young men were the sons of Germanicus, the hero who had been poisoned

to death back in 19 AD. Thanks to Agrippina, daughter

of the infamous Julia, both young men carried

the cherished "Julian Blood". Sejanus could have cared

less about the blood line problem, but he was concerned that

these two boys had were the new direct heirs to the throne.

It might

surprise you to know that Tiberius not only knew about each

of these moves, he approved them. Since Sejanus

controlled the flow of information that reached Tiberius on

Capri, he was able to build trumped up cases against each

that enraged the old man. Tiberius didn't care about

the loss of these two heirs. He despised their mother.

Agrippina, wife of the deceased Germanicus,

had long been a thorn in Tiberius' side. For years she

had publicly accused Tiberius of complicity in her husband's

poisoning. Whether she spoke the truth or not, one

thing is certain - Tiberius had grown to hate Agrippina with

a purple passion. He was more than happy to have

Sejanus dispose of Agrippina and her two sons if for no

other reason than to simply shut her up. However,

before he sent her away, Tiberius granted her a face to face

meeting where she attempted to warn him about Sejanus.

The old man refused to listen to her, but a seed of doubt

had at least been planted. And then he sent her into

exile. Too bad; this woman had a lot of courage.

And she paid for it with her life.

In 29 Agrippina and her eldest son Nero

Julius Caesar were deported; her second son,

Drusus Julius Caesar, was imprisoned in 30. Nero Caesar was banished to

an island, Drusus Caesar was imprisoned in the cellar of the

imperial palace. In 30 AD Nero Caesar, age 24,

was ordered to commit suicide; in 33 AD, Drusus Caesar, age

26, was starved to

death in prison. Sejanus had nearly destroyed the entire Julio-Claudian

line!

There was only one left. The only surviving son of Germanicus as heir

to the throne was the young Gaius (Caligula).

Through some bizarre twist of fate, Caligula escaped almost

certain elimination when Tiberius ordered him brought to

Capri to stay with him. This timely action is the only

thing that kept Caligula, the eventual heir, from suffering

the same fate at the hands of Sejanus as his two brothers.

Sejanus wasn't

worried. He controlled complete

access to Tiberius, whose position on Capri made him

virtually inaccessible to any messages. No one could tell Tiberius

what was really going on back in Rome! That

meant Sejanus had all the time in the world to assassinate

Caligula when the opportunity presented itself, most likely

immediately after the natural death of the emperor, a time

that seemed close at hand.

Sejanus' power reached its

zenith when Tiberius promoted him to the same consular

office that Tiberius held in 31 AD.

Emboldened by

the promotion, Sejanus travels to Capri to petition Tiberius

again to allow him to marry Livilla.

Now, to his

great relief and surprise, Tiberius seemed to withdraw his opposition to Sejanus

marrying into the Imperial family. However, for some

reason, Tiberius remains reluctant to give permission to

marry his daughter-in-law (and niece) Livilla.

Instead, Tiberius, now 73, threw the oddest twist at

Sejanus. He said Sejanus had permission to marry his

granddaughter, Livia Julia.

Sejanus smiled

and frowned simultaneously.

On the hand,

Sejanus was thrilled. Finally! This would be his

way into the Imperial family. Privately speaking,

Sejanus had no objections to marrying Livia Julia, a 26 year

old beauty.

On the other

hand, Sejanus suspected Livilla, his mistress, would throw

an absolute fit. Perhaps it would help to mention that

Livia Julia was the daughter of Livilla.

Maybe Sejanus should run this by Livilla before accepting.

On the other hand, if he gave Tiberius time to think about

it, maybe the Emperor would change his mind.

Unfortunately,

Livilla was back in Rome hundreds of miles away and Tiberius

wanted an answer now. Better to say 'yes' now than to

take a chance. Sejanus said this

arrangement would be suitable to him.

On his trip

back to Rome, Sejanus was in a very good mood. Surely

Livilla would understand. He had an excellent

explanation to tell Livilla. After all, Tiberius was

so old, he could keel over any moment. Once he was

dead, Sejanus would simply call off the wedding and be free

to marry Livilla instead.

Sejanus knew

that once he was married

into the Imperial family, he would become a patrician and

eligible for succession to the throne. With all the

heirs except Caligula murdered, Sejanus would have the

inside track. Even if Tiberius named Caligula his

heir, Sejanus assumed getting rid of Caligula would not pose

much of a problem. The moment Caligula returned to

Rome, one of his guards could assassinate Caligula in broad

daylight and there was no power in Rome that would dare

cross Sejanus.

Sejanus was certain the die was cast in his favor. He

was wrong. The Fates had a nasty surprise for Sejanus.

Beware the

Wrath of a Woman Scorned

No matter how

powerful a man is, if he is human, then he is vulnerable

somewhere. Even Achilles, the greatest warrior in all

of mythology, had a vulnerable spot that cost him his life.

Sejanus

enjoyed a powerful position, but he was still not in

complete control unless he could become Emperor. As

long as Tiberius lived, Sejanus worried that his activities

might be discovered by the old man.

If Sejanus had a weakness in the world, it would be his

disdain for women. Sejanus used women on his climb to

the top, but he failed to treat them properly when he

disposed of them. No one is angrier than a woman who has

been rejected in love. For that matter, nothing drives

a mother crazier than one who sees her children forcibly

taken from her by their father.

Sejanus was about to learn the hard way that you should be

careful with people you have relationships with because when

some people get hurt (real or imagined) they might go crazy

trying to get revenge.

|

|

Sejanus' first mistake

was his treatment of Apicata, the wife of his three

children. Once he had his sights set on marriage to Livilla,

Sejanus had the sense to divorce his wife well ahead of time before

approaching Tiberius. At a certain point after the divorce,

Sejanus decided his children should come live with him permanently at the

palace. In an act of sheer spite, Sejanus made certain his former wife had no access to the

children. Even though she had done nothing wrong, Apicata had lost her children.

Apicata was beside herself with grief.

Sejanus' second

mistake was assuming his mistress Livilla would cooperate with

Tiberius' strange offer for Sejanus to marry her daughter.

Tiberius' reason for rejecting Sejanus' request was oddly paternal.

He was concerned that his niece and former daughter in law Livilla,

having been the sister of the powerful Germanicus, first heir to the

throne, and the wife of the powerful Castor, second heir to the

throne, would never be satisfied in the long run married to a lowly

Praetorian Guard like Sejanus!

Sejanus was apoplectic

with this remark. Lowly Praetorian Guard? Tiberius was so completely in the dark as to

what was really going on that he had no idea Sejanus had become the

most powerful man in the world, more powerful in most ways than even Tiberius

himself!

However, on the other

hand, Tiberius needed Sejanus. Why not throw the dog a bone?

Tiberius offered him the hand of his forlorn granddaughter

Livia Julia. And why was she forlorn? It seems poor Livia Julia had recently

been engaged to Nero

Caesar, one of the men Sejanus had just exiled from

Rome and soon to be dead. Tiberius figured a marriage to Sejanus might just

perk her up a bit!

Ah, those romantic

Roman men. Aren't they special!

Showdown with Livilla

By definition, any

woman who murders her husband in cold blood is

probably not the most reasonable woman in the world to begin with. Now that

Sejanus was betrothed to his future wife Livia Julia, he assumed his

partner in crime would be a bit miffed, but eventually come around to the

idea.

After all, this is what they wanted... with this marriage, Sejanus

could now become

emperor and Livilla would be the true power behind the throne.

And, uh, plus Livilla's sexy daughter would become Empress.

What good mother doesn't want to see her daughter become Empress? Wouldn't

this be wonderful?

If I may interject something, I don't think Sejanus understood

women very well. When Sejanus accepted Tiberius' offer

to marry the young lady, he may have overestimated his

ability to charm Livilla into acceptance.

The first words out of her astonished mouth, "Oh,

you'd like that, wouldn't you! Get to be Emperor, sleep with the mother, sleep

with the daughter or maybe sleep with both of us at the same time. I'll

be damned if I am going to let you get away with this!"

Sejanus did his best

to reason with the woman. Why would she not cooperate?

"Cooperate?

Are you out of your mind? You will marry that girl

over my dead body!!" No truer words were

ever spoken.

If he had any brains, Sejanus would have told Tiberius he

loved Livilla and wanted to make her happy... and stuck to

his guns. Oh well, it might too much to expect

a monster like Sejanus to suddenly develop sensitivity towards

women. Like most

Roman men, he was used to treating women like property.

Sejanus expected Livilla would eventually toe the line and accept

her fate. He was wrong. Dead wrong, as they say.

This mistake would cost him his life.

Apicata Strikes Back

A mother

stripped of her children is just like a wounded she-bear.

She will do whatever it takes to get her children back.

Sejanus would not let her see her children under any

circumstances. Apicata decided she would speak to

Antonia, the only woman in the Imperial Family with any

sense of decency.

Antonia was

aware of her daughter Livilla's infatuation with Sejanus.

Antonia was also aware that Sejanus had brought the children

to the palace and denied their mother access to them.

Unfortunately, Antonia explained that she had no control

over the behavior of Sejanus. There was nothing she

could do. Surely Apicata already knew this. Why did Apicata come to her in the first

place?

That is when

Apicata dropped a bombshell. A slave of Livilla had

whispered to Apicata that she had seen Livilla mixing the

poison administered to her husband Castor. Antonia's

mouth dropped open with shock. Her own daughter had

just been accused of murder!

That is when

Antonia told Apicata she didn't believe a word she said.

Furthermore it was time for Apicata to leave.

However, in

the quiet of her bedroom, Antonia despaired. A powerful

seed of doubt had been planted in her mind.

Furthermore,

the household was in an uproar at the moment. In a

rage, Livilla had told her mother that Sejanus was thinking

of marrying her daughter. Now Livilla was throwing