| |

The War of the

Roses

ACT TWO:

Warwick's Betrayal

|

| |

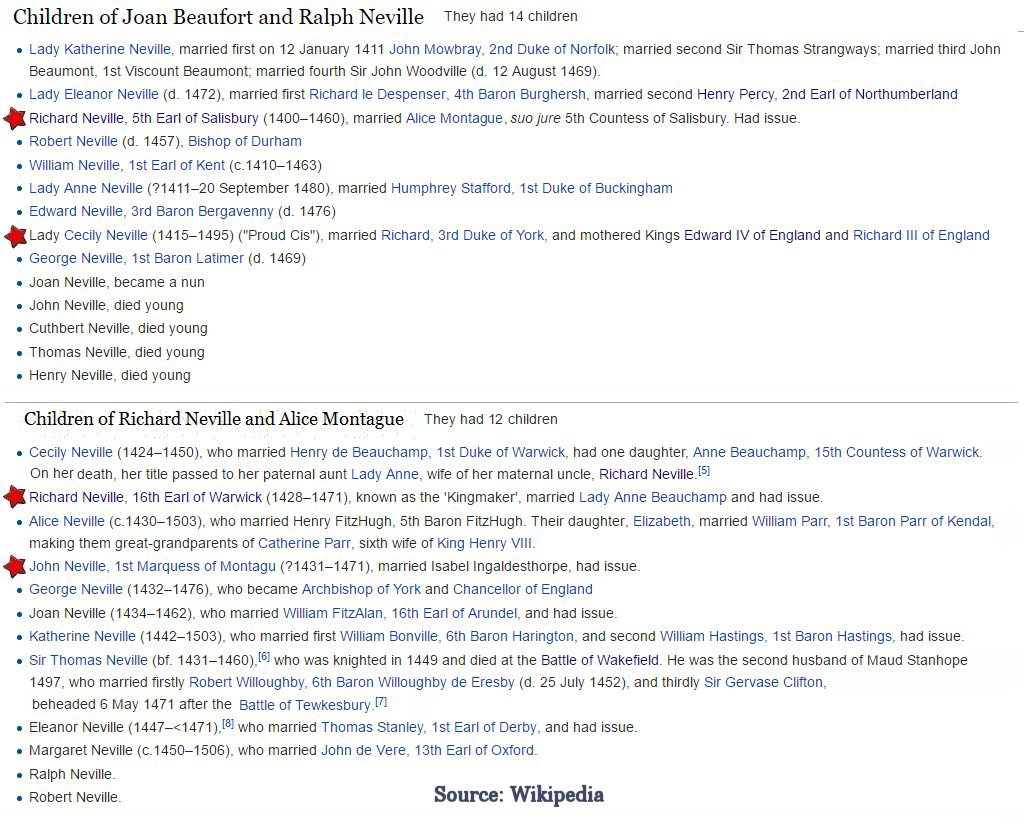

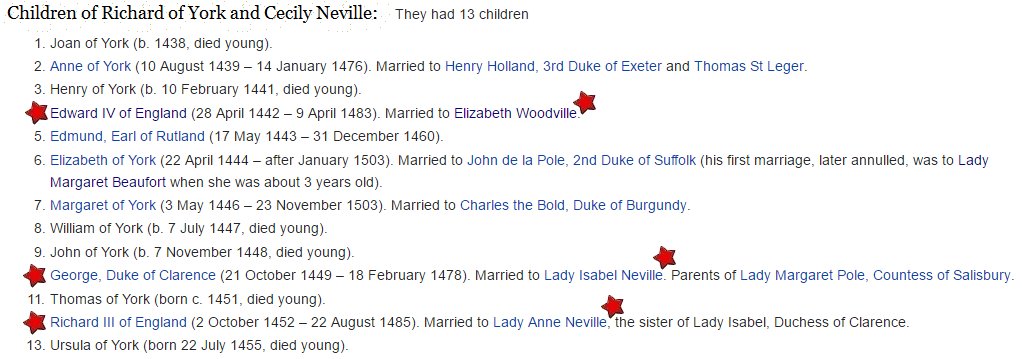

The House of

Neville

Nothing

that takes place from here will make any sense

unless we first discuss the House of Neville.

There

are two things to know about the Nevilles.

First

and foremost, the Neville wives reproduced at an

unimaginable, unfathomable rate.

Second,

they were the richest family in England which is a

good thing because they had a lot of mouths to feed.

|

|

|

|

So far we have talked about

the Plantagenets, the Anjevins, the Lancasters, the

Beauforts, and the Yorks. Now it is time to

discuss the Nevilles.

Like everyone else in this story, John of Gaunt is

somewhere in the background of the House of

Neville. However, so is

Joan Beaufort. The House of Beaufort

will soon figure prominently in our story.

In

particular, Richard Neville, or 'Warwick' as

he was known, intermingled with the family of

Richard, Duke of York. For starters, Warwick's

Aunt, Cecily Neville, was Richard of York's wife.

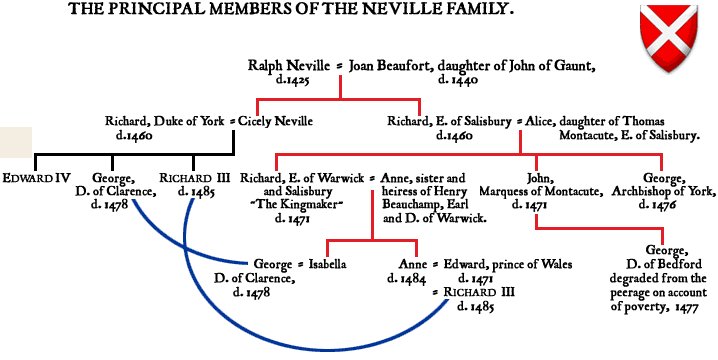

Warwick

had two daughters. Isabella Neville married

George, son of Richard of York. Anne Neville

married Edward, Prince of Wales, but then later

married Richard III, son of Richard of York.

|

|

Cecily Neville and

Richard of York

Cecily

Neville married Richard of York in 1429. Oddly

enough, they grew up together in the same household.

Richard's mother, Anne Mortimer, died giving birth

to him. Richard's father, the Earl of

Cambridge, was beheaded in 1415 for his part in the

Southampton Plot against the Lancastrian King Henry

V. Although the Earl's title was forfeited, he

was not 'attainted'. The four-year-old

orphan Richard became his father's heir.

Within a few months of his father's death, Richard's

childless uncle, Edward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of

York, was slain at the Battle of Agincourt on 25

October 1415. King Henry V allowed Richard to

inherit his uncle's title and the lands of the Duchy

of York. The lesser title of the Earldom of

March also descended to him on the death of his

maternal uncle Edmund Mortimer, 5th Earl of March.

Here is

what is interesting. Richard of York may have

been an orphan, but he was also to become the

wealthiest and most powerful noble in England,

second only to the king himself.

As he was an orphan, Richard's income was managed by

the Crown. The Wardship of such an orphan was

therefore a valuable gift of the crown. In

October 1417 this was granted to Ralph Neville, 1st

Earl of Westmorland, who adopted Richard probably

because Ralph Neville didn't have enough children of

his own. Mind you, I am telling a little joke

here. Ralph Neville had a problem... he had

lots of daughters and needed some suitable husbands

for them. Neville had fathered an enormous

family (twenty-three children, twenty of whom

survived infancy, through two wives). With so

many daughters needing husbands, Ralph Neville

basically went out and bought one for Cecily.

As was

his right, in 1424 Ralph Neville betrothed the

13-year-old Richard to his daughter Cecily Neville,

then aged 9. This was a bit on the weird side

since Cecily was growing up right beside Richard.

This was like Greg marrying Marcia on the

Brady Bunch. However, they obviously

overcame any reticence. Cecily and Richard

would have 13 children. Like I said, those

Neville girls knew how to reproduce.

The major point is that Richard of York grew up as a

Neville and maintained close ties with the family

throughout his life. Richard's wife Cecily was

a Neville and Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, i.e.

The Kingmaker, was his closest advisor.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

Elizabeth Woodville

|

|

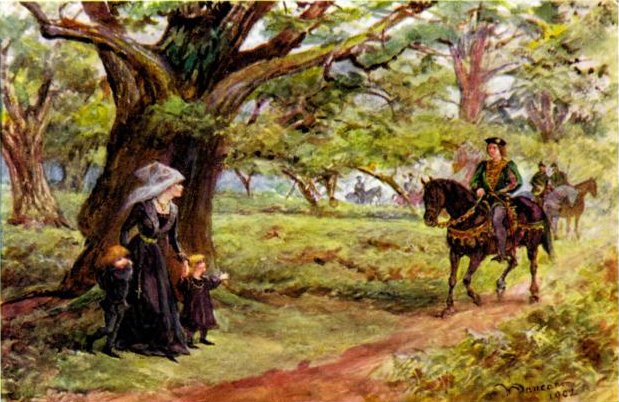

While the thirty year War of the Roses was

quite the bloody matter, it had the redeeming

quality of being centered around a very curious

romance. Believe it or not, Edward had

the nerve to marry an upstart. And get this...

Edward did for it love. Can you imagine that?

The

scandal was unbelievable. No one married for

love back in Old England. Strangely enough,

Edward's decision was so upsetting that it would

create Chapter Two of the War of the Roses.

Richard Neville, Earl of

Warwick, 'The Kingmaker', was the man who had

put Edward IV on the throne. Warwick and

Richard of York saw eye to eye on many things.

After Richard of York died at Wakefield, Edward IV,

depended greatly on the patronage of Warwick for

advice, for fighting men, and for political

influence.

Edward was 19 when he became

king and Warwick was 33. One can imagine

Warwick's relationship with Edward was that of an

older brother and a mentor. At this point, Earl of Warwick saw

himself as Edward's closest confidant and the power behind the throne.

One can also imagine that Warwick believed that

Edward 'owed him' for making him King in

1461. Three years had passed. At the

moment, Warwick was in France pursuing a suitable political

marriage on behalf of Edward.

Warwick had made preliminary

arrangements with King Louis XI of France.

Edward would either marry either Louis' daughter

Anne or his sister-in-law Bona of Savoy. Warwick

had done a good job... he

had the daughter of the King of France lined up.

Not bad.

But then Edward went and botched everything up.

Ordinarily an English King marries a suitable girl.

Then if by chance he met a hottie in the woods, he has the sense to

take the young lady to a convenient

cottage somewhere. That is exactly what Edward had in mind when

one day he just happened to meet

Elizabeth Woodville in the forest of all places.

Their meeting reads like a Fairy Tale. The

only way to make it any better would be to name the

forest 'Woodville' as well.

|

| |

|

|

Who was

Elizabeth Woodville and what she doing here in

Woodville? Elizabeth was an impoverished widow with

two hungry sons to feed. In 1452 Elizabeth

had married Sir John Grey. John Grey was a

supporter of the Lancastrian cause who died fighting

at the Second Battle of St Albans in 1461 against

Edward, Duke of York.

Disastrously for Elizabeth, after Grey's death, her

mother-in-law refused to pay her dower from the

family estate. Only the king himself would be

able to enforce her rights.

As the

wife of a leader on the losing side, Elizabeth

Woodville was now a penniless outcast without an

estate. She was forced to return to

live with her parents in Grafton.

Three

years had passed since her husband's death.

One day in 1464, Elizabeth learned that Edward

was in the area to recruit new men for his army.

Even better, the king was hunting in a forest near Grafton. Elizabeth

deliberately

hid behind a tree and stepped out onto

the road with her two boys as young King Edward

passed by on his horse.

|

| |

|

|

Edward was a known ladies man with a different

mistress stashed in virtually every shire of the

Kingdom. Noticing that Elizabeth was unusually

beautiful, the king stopped.

Edward climbed off his horse and began to chat.

Elizabeth used her opportunity to plead for the

return of her husband's estates. Edward

was smitten. He immediately suggested they

meet at a nearby cottage to further discuss the matter

of Elizabeth's lost estate, but

Elizabeth turned him down. Edward, a notorious

womanizer, was unaccustomed to rejection. He

continued to pursue Elizabeth and she continued to

keep him at arm's length.

Elizabeth may have been a commoner, but she knew how

to use her uncommon beauty to great effect.

Edward became very intrigued. Here

was a woman who had so much to lose if he failed to

grant her wishes. She maintained her virtue

nonetheless. Edward

began to admire Elizabeth not just for her beauty,

but for her determined refusal to be his mistress.

Finally

Edward couldn't take it any more. Edward was

full of desire for this fetching woman.

Elizabeth not only had the beauty he desired in a

wife, she possessed a strong, virtuous character.

Edward proposed and the two of them had a secret

marriage.

Soon

after, King Edward IV,

England's most eligible bachelor, shocked the nation

when he announced he had taken a

bride. Elizabeth Woodville, the impoverished

widow with two young sons, was the new Queen of

England.

|

| |

|

Angry Reaction

to the Edward's Surprise Marriage

|

|

|

|

The

wealthy elite of England were aghast. The

match was badly received by the Privy Council.

"Surely, Edward, you must have known that this is

no wife for a prince such as yourself."

Yes,

Edward knew full well that he was in trouble.

He had knowingly backed out of an arranged marriage

without consulting Warwick, the man who had gone to

considerable trouble to arrange a suitable marriage

for Edward. Warwick was furious about Edward's

surprise marriage. Edward had

gone and done something stupid without even speaking

to him. Warwick was the one who would have to

apologize to the King of France. Warwick felt humiliated and

betrayed. After all he had done to help

Edward, he expected to see some respect and maybe

even a little gratitude.

Margaret

of Anjou was disgusted.

Margaret was

still determined to win

back her son's inheritance.

After the Battle of Towton, she fled with

her son

and husband to Scotland

and then on to France.

From there, Margaret fumed. As soon as Edward

had a male heir, it was all over for her son.

Edward's mother Cecily

Neville was unusually bitter at her oldest son. Cecily Neville was at

the very top of the social scale in late medieval

England, and held the highest status any woman could

enjoy. Cecily felt both Elizabeth and the

entire Woodville family were social upstarts

"I

think of this commoner

strumpet waiting for the King of England

under an oak tree, as if she just happened to be

by the roadside, a hedge-witch casting her

spells on a gullible fool

such as yourself. I did not raise you to

fall for the

amorous glance of a

slut strutting her well-worn wares

in the forest."

|

|

The Kingmaker

Warwick

became the central figure in the Second Chapter of

the War of the Roses. He bore a grudge towards

Edward that simply grew worse. In a sense, he

possessed the same burning ambition as his deceased

ally Richard of York. Warwick knew he could

not be king, but he was willing to settle for being

the man who decided who would be the king. And

for that matter, Warwick was determined to make one

of the two daughters, Isabella and Anne, the next

Queen.

Edward's

marriage to Elizabeth initiated the rift in 1464.

The animosity between the two men widened year by

year. Warwick was angry about everything to do

with Edward. And he hated Elizabeth just as

much. Elizabeth considered Warwick dangerous

to the extreme.

Elizabeth was right, but her husband constantly

sought to appease his former mentor. It did

not good. Warwick did not approve of anything

Elizabeth did. With the arrival on the scene

of the new queen came many of her relatives.

Elizabeth's twelve unmarried siblings suddenly

became very desirable matrimonial catches.

Warwick watched with disdain as Elizabeth's marriage

greatly enriched her siblings and children.

Some were appointed to royal offices, some married

into the most notable families in England, some did

both.

The

major reason for Warwick's hostility was his

increasing loss of political influence. These

people were upstarts, pretenders. These people were

getting in his way. Warwick's animosity grew

as the Woodvilles opposed policies favored by

Warwick. Seeing the upstarts successfully

exploit their influence with the king to defeat him

grated at Warwick no end. Warwick refused to

let his alliances with the most senior figures in

the English Council and the divided royal family be

compromised. When Elizabeth Woodville's

relatives, especially her brother Anthony Woodville,

2nd Earl Rivers, began to challenge Warwick's

pre-eminence in English society and political

circles, Warwick decided he had to do something.

Three

years had passed since Edward's marriage to

Elizabeth. During this time, Warwick had

become progressively more alienated from King

Edward. Now his intentions turned toward

treason.

|

Games of

Thrones Revisited

Rick's Note: Let's put our story on pause

for a moment while I remind everyone that

there are entire websites devoted to

comparing the real life characters in the

War of Roses to George RR Martin's fictional

Game of Thrones characters.

Margaret of Anjou is Cersei. Richard

of York is Ned Stark. Ned Stark had

his head on a pike. So did Richard of

York.

Lord Walder Frey is the equivalent of

Warwick. Lord Frey supported Robb

Stark’s military action by letting Robb's army

cross the bridge. However, Lord Frey

expected compensation for his indispensable

support. Robb Stark promised to

marry his daughter. When Robb Stark

reneged to marry for love, Walder Frey

arranged the infamous Red Wedding.

Game of Thrones is not a direct parallel of

War of the Roses. But there are times

when the similarities are uncanny.

Given my fascination with Game of

Thrones, it is easy to understand why

I am just as fascinated by the War of the

Roses. Look what ambition does to

people.

|

Click the picture or this link

War of Roses-Game of Thrones

to view a fabulous video which explains the

War of Roses in 6 minutes. You will

understand the whole story so much more

clearly.

|

|

|

| |

Treachery

Warwick

bore a grudge towards Edward that had become

intolerable. Years of hostility and a battle

of wills had turned into open discord between King

Edward and Warwick. Warwick decided to switch

his allegiance to the Lancastrian cause. If a

Kingmaker can make a King, then a Kingmaker can

unmake a King.

In the

autumn of 1467, Warwick withdrew from the court to

his Yorkshire estates. Now out of sight,

Warwick covertly instigated a rebellion against the

king with the aid of Edward's disaffected younger

brother George, Duke of Clarence, as well as

encouragement from

Edward's bitter mother, Cecily. Keeping in

mind that Cecily Neville was Warwick's niece,

Warwick had little trouble gaining her support.

Cecily

had never forgiven Edward for marrying such a

low-life.

From the start, Cecily had refused to subordinate

herself to the new queen, styling herself as the

true Queen, or 'Queen

by right' as she put it. Cecily had never

quite gotten over the fact that she would have been

the queen had Richard of York not been murdered.

Now her son Edward expected Cecily to show respect

to this low-born woman. Cecily would have

nothing of it. This Elizabeth woman was

beneath her, so how could her son ever expect her to

bow to such a woman who was beneath her?

Edward

could see there was no love lost between Cecily and

her daughter-in-law Elizabeth. To lessen

tensions at court, Edward IV had new Queen’s

chambers built at Westminster for Elizabeth just so

Cecily could remain in her old chambers. He

had tried to mollify his mother, but it did no good.

Cecily had left for good in a show of disgust. She had

a meeting with Warwick to attend.

|

|

George

Plantagenet, Brother of Edward

If

someone was looking for a part to play in this

ongoing drama, George Plantagenet was one role to

avoid for sure. First a loser, then a winner,

then a loser again, this guy would eventually suffer a miserable

fate. The poor guy couldn't even get a decent

picture drawn.

George,

born 1449, was the middle brother between Edward,

born 1442 and Richard, born 1452. When Edward

became king, he treated both of his brothers well.

The new king was generous to his two younger

brothers. George, 11, was made the Duke of

Clarence in 1461 and the younger, Richard, 8, became

the Duke of Gloucester. From this point

forward, George became better known as 'Clarence'.

There

must be something very seductive about the idea of

becoming king. Rather than settle for the good

life he had, George was ambitious to become king

himself. Consequently George was easy prey for

the Kingmaker's promises in 1469. Not only could

George marry his daughter Isabel, Warwick would make

George the next King. How could George refuse

an offer like that? So what if his

generous brother Edward had to go? Tough luck,

bro. George allowed himself to be used

like a pawn in the ugly power struggle

between Warwick and King Edward.

|

| |

Meanwhile, Back at

the Ranch...

This excerpt

from the White Queen written by

best-selling author Philippa Gregory. Here Edward

is speaking to his wife

Elizabeth about rumors of Warwick's plot.

‘But now I have to go north and deal with this,’

Edward complains to me.

‘There are new rebellions

coming up like springs in a flood. I thought it was

one discontented squire but the whole of the north

seems to be taking up arms again. It is Warwick, it

must be Warwick, though he has said not a word to

me. But I asked him to come to me; and he has not

come. I thought that was odd – but I knew he was

angry with me – and now this very day I hear that he

and George have taken ship. They have gone to Calais

together.

God damn them, Elizabeth, I have been a

trusting fool. Warwick has fled from England, George

with him, they have gone to the strongest English

garrison, they are inseparable, and all the men who

say they are out for Robin of Redesdale are really

paid servants of George or Warwick.’

Elizabeth thinks to herself, 'I am aghast.

Suddenly the kingdom which had seemed quiet in our

hands is falling apart.'

"It must be Warwick's plan to use all

the tricks against me that he and I used

against Henry."

Edward hesitates, then begins thinking

aloud.

"He is backing George now, as he once

backed me. If he goes on with this, if

he uses the fortress of Calais as his

jumping point to invade England, it will

be a brothers' war as it once was a

cousins' war. This is damnable,

Elizabeth. And this is the man I thought

of as my brother. Warwick is my kinsman

and my first ally. For God's sakes, this

was my greatest friend. And now he has

turned on me! And turned my brother as

well. And now I hear even my

mother. My God, my own mother."

Philippa Gregory, The White Queen

|

| |

The Curious Blaybourne Allegation

| |

|

|

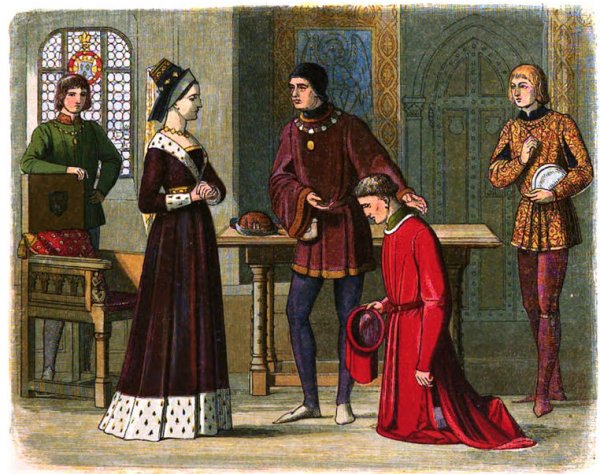

The following remarkable conversation takes

place in 1464 shortly after Edward has

finally revealed his secret marriage to his

mother Cecily Neville. This excerpt

was written by Philippa Gregory in her

best-selling novel The White Queen.

Jacquetta Woodville is known as the

Lady of the Rivers due to her

unusual gifts of second sight. She is

rumored to have remarkable powers of

divination. Cecily Neville is well

aware that the Woodvilles are Lancasters.

Not only that, Jacquetta became a close

confidante of none other than Margaret of

Anjou, the virago Queen herself, long before

all the fuss started.

As we know, the Duchess of York absolutely

hit the roof upon discovery of the marriage.

To her, Elizabeth is the enemy.

Desperate to calm his mother, Edward asked

Jacquetta to meet with Cecily, the Duchess,

and attempt to restore peace in the family.

Jacquetta is not welcome here. No

doubt it is Jacquetta's relationship with

Margaret of Anjou, sworn enemy of the

Neville family, that has raised Cecily

Neville's darkest suspicions about Elizabeth

Woodville. Furthermore, Jacquetta was

the only person in attendance at the secret

wedding of Edward and Elizabeth besides the

priest. It is upon Jacquetta's word

that Cecily Neville has to believe the

wedding even took place.

In attendance during this tension-filled

meeting are several of Cecily's daughters

including Margaret of York as well several

of Jacquetta's daughters including Anne

Woodville.

Anne Woodville, Jacquetta's second daughter,

narrates the story here.

Cecily Neville, Duchess of York, is

speaking to Jacquetta and the various

daughters in the room.

"Nonetheless, Elizabeth was not my

choice, nor the choice of Lord

Warwick."

Her Grace is upset, her voice

trembling with anger.

"It would mean nothing if Edward

were not king. I might overlook it

if he were a third or fourth son to

throw himself away..."

My mother (Jacquetta) replies,

"Perhaps you might. But it does not

concern us. King Edward is the king.

The king is the king. God knows, he

had fought enough battles to prove

his claim."

Cecily Neville retorts,

"I could prevent Edward from being

king," Cecily rushes in, temper

getting the better of her. "I could

disown him, I could deny him, I

could put George on the throne in

his place.

How would you like that as the

outcome of your so-called private

wedding, Lady Rivers?"

The duchess' ladies blanch and sway back

in horror. Margaret (Margaret of

York) who adores her brother Edward,

whispers, "Mother!" but dares say no

more.

Edward has never been their mother's

favorite. George, Edward's younger

brother, is his mother's darling, the

pet of the family. Richard, the

youngest of all, is the dark-haired runt

of the litter. It is incredible

that the Duchess speaks of putting one

son before another, out of order.

"How?" my mother says sharply,

calling the Duchess' bluff. "How

would you overthrow your own son?"

The Duchess replies,

"If he was not my husband's

child..."

"Mother!" Margaret wails.

"And how could that be?" demands my

mother, as sweet as poison.

"Would you call your own son a

bastard? Would you name yourself a

whore? Just for spite, just to throw

us down, would you destroy your own

reputation and put cuckold's horns

on your own dead husband? When they

put Richard's head on the gates of

York, they put a paper crown on him

to make mock. That would be nothing

compared to putting cuckold's horns

on him now. Would you dishonor your

husband? Would you dishonor your own

name? Would you dare shame your

husband worse than his enemies did?"

There is a little scream from the women,

and poor Margaret staggers as if to

faint. My sisters and I are half-fish,

not girls. We just goggle at our mother

and the king's mother go head to head.

It is like a pair of slugging battle-axe

men in the jousting ring, each saying

the unthinkable.

"There are many who would believe

me," the king's mother threatens.

Mother stares at the Duchess with

contempt.

"More

shame to you then,"

my mother says roundly.

"The rumors

about Edward's

fathering reached England.

Indeed.

I

was among the few who swore that a

lady of your house would never stoop

so low. But

I heard, we all heard, gossip of an

archer named – what was it –’

my mother

pretends to forget and taps her

forehead. ‘Ah, I have it: Blaybourne.

An archer named Blaybourne, who was

supposed to be your amour.

But

I said, and even Queen Margaret

d’Anjou, sworn

enemy of your husband, said

that a great lady like you would not

so demean herself as to lie with a

common archer and slip his

bastard into a nobleman’s cradle."

The name 'Blaybourne'

drops into the room with a thud like

a cannonball. You can almost hear it

roll to a standstill. My

mother is afraid of nothing.

Mother is not through yet.

‘And anyway, if you can make the

lords throw down King Edward, who is

going to support your new King

George? Could you

trust his brother Richard not to

have his own try at the throne in

his turn? Would

your kinsman Lord Warwick,

your great friend, not want the

throne on his own account?

Philippa Gregory, The White Queen

|

| |

|

Now we

fast-forward five years. It is 1469 and

Warwick is planning a revolt.

Warwick's

plan is to unseat Edward IV and replace him with

George, Duke of Clarence. Warwick thought it

useful to undermine Edward's legitimacy prior to

launching the battle campaign by spreading an ugly

rumor. Mind you, Cecily Neville, 54,

was Warwick's aunt and George's mother. One

has to assume that Warwick and George would not act

without her permission.

In 1469

both Warwick and George

began

to spread rumors that the king was a bastard.

People were asked to believe that his true father was not

Richard, Duke of York, but

rather an obscure archer named Blaybourne.

(Those Archers have always caused trouble!)

With Warwick pushing for the crown to

pass to her second son, George, Duke of Clarence,

there is evidence that Cecily cooperated with

the public shaming of her son. Although

Cecily said little about the matter in public,

she didn't deny it either.

After

all, this was a woman who lived for her high status

in the Royal Court.

This was not exactly the kind of information one

typically uses to advance their social standing in snooty circles...

'Hey,

girls, wanna hear some juicy gossip? Guess

what? I fucked some archer kid back in

1442 and got knocked up! Blimey,

we've got a bastard for a king! If that

doesn't beat everything...'

One

would assume a woman of Cecily Neville's importance would have

spoken up after being accused of adultery.

Instead... silence.

That speaks

volumes without saying a word.

So was

the Blaybourne rumor true or not? There are

four pieces

of circumstantial evidence to support the claim.

•

During

the critical time needed for

Edward's conception his father Richard,

Duke of York, was away

from his home base in Rouen,

France, for a period of five weeks.

He was busy

overseeing the Siege of Pontoise over a hundred miles

away, a distance which necessitated several days of marching.

In his absence, his wife

Cecily was (allegedly) having an

adulterous fling with an archer by the name of Blaybourne.

•

Further

evidence reveals that Edward's

ho-hum baptism

ceremony was held in a

side chapel in stark contrast to

the glorious baptism

of his next brother, Edmund.

•

Cecily Neville did not publicly recant.

•

Oh,

one more thing, Edward was tall and fair

and did not look

a bit like his

father, short and dark.

So was

Edward illegitimate? Maybe. Maybe

not. 650 years after the fact there are

lengthy blogs all over the Internet written by

people who claim to know the truth. Each

person offers compelling reasons why they are right

and why the next guy or gal is wrong.

If the

allegation was true, the assumption would

have meant that George was

the rightful king. Therefore

Warwick was using this as his rationale to put the

rightful king on the throne. Oh, how noble of

Warwick to spare England the shame of yet another illegitimate

king!!

What makes

all of this so hypocritical is that William the

Conqueror was illegitimate. No one

questioned his right to rule, so why should it

matter in the case of Edward? After all,

Edward's father never said a word. No doubt

Richard was able to count the weeks as well as

anyone. If anyone

should be upset, it should have been him.

Therefore, what difference did it make?

Here are

the facts.

Richard of York

loved his son Edward and the feeling was mutual.

Edward risked his

life in battle after battle trying to make his

father the next king. When Richard

fell, it was Edward who vowed to avenge his father.

Edward won the brutal Battle of Towton, the most

horrible skirmish in English history, despite being

badly outnumbered. It takes considerable guts

to stand up and fight against larger forces.

28,000 men died and now suddenly people are supposed

to care who his mother slept with? If

anything, the entire nation should have been up in

arms against his mother. This was her doing,

not Edward's. I guess one

has to be British to understand.

Why would

Cecily and Warwick stoop so low? Oh, forget

about Warwick. He had no more scruples than a

shyster lawyer.

To me, the

real story here is that Edward's mother would

cooperate with this mockery. Even if this

story was true, what did Edward ever do to his

mother to deserve her treachery? Okay, so Edward

married a sexy wood nymph instead of a proper French girl with a pedigree and a

big dowry. Get

over it!!

A normal mother would

have been proud out of her mind. Not Cecily.

Cecily allowed her contempt to dominate her sense of

decency.

Look at

Edward... a courageous man who had fought bravely to

become the King of England!!!! Whether

Edward was legitimate or illegitimate, for God's

sakes, why would a mother hurt her son like this?

Even if Edward was illegitimate, it wasn't his

fault. Cecily had abandoned her son.

What in the hell was wrong with

this woman?

|

|

In 1469,

with his influence at

the

English court waning,

Warwick had

won over Edward's brother George. With full

approval of Warwick's aunt Cecily Neville, Warwick

pledged his daughter Isabel in matrimony and

promised to install George as the next king with

Isabel as queen. The nineteen-year-old George

had shown himself to share many of the abilities of

his older brother, but was also jealous and

overambitious. In July 1469, the two sailed

over to Calais where George was married to Isabel.

From there they returned to England, where they

gathered the men of Kent to join the rebellion in

the north.

Edward had taken his eye

off the ball. The main part of the King's army

(without Edward) was defeated at the Battle of Edgecote Moor on 26 July 1469. This defeat

would not have been decisive if Edward himself had

remained at liberty, but he walked right into a

trap. Heading north to meet up with his

retreating army, Archbishop Neville, brother to

Warwick, had been lying

in wait. Edward was subsequently captured at

Olney. Although treated with formal respect,

Edward was nonetheless imprisoned.

Sad to say, Edward was largely to

blame for the humiliating debacle of July 1469. His

complacency shows that he underestimated the extent

to which he had lost popular sympathy. In addition,

he seemed unable to accept the extent of treachery

within his own family. Denial was the only possible

explanation for his hopeful loitering for three

weeks while the rebels organized.

His blunder into captivity further

underscored his lack of appreciation for the danger

he was in. Above all, Edward had failed to

appreciate just how little his government had

succeeded in winning popular support when faced with

a rival of Warwick's considerable reputation.

However, strangely enough, Warwick

was unable to exploit his stunning victory. He

found himself politically isolated. The English

Council refused to cooperate. Warwick needed more

backing for his illegal usurpation,

especially he intended to shove George,

Duke of Clarence, down their throats.

The people of London took Warwick's

triumph as a license for violence. They began to

riot and pillage. There

were local revolts throughout the land when some of

the nobility seized the chance to settle their

private quarrels without interference from the

government. To his

dismay, Warwick discovered he could get no response

to his proclamations calling for troops as long as

the people believed the

king was a prisoner. Warwick shrugged his shoulders

in bewilderment and

resignation. The people of

England had spoken. Only the moral authority

of the king could command their

obedience.

In disgust, Warwick was forced

to release Edward on 10 September 1469.

By October Edward's power

was restored.

An

important lesson had been learned here. In

order to rule a Kingdom, even a powerful man like

Warwick could not succeed without the will of the

people. The coup d'état may have failed, but

this was a very close call.

One has to wonder.

Edward had been betrayed the man who had once been

like a father to him. He had been betrayed by

his brother. And he had been betrayed by his

own mother of all people.

Prior to reading this story,

the only place where people behaved this badly was

on the Game of Thrones. It is

shocking to discover what I thought was escapist

nonsense could be possible in the Real World.

|

| |

An Uneasy Peace

During Edward's capture, Elizabeth had been terrified

her husband would simply be murdered. Why Warwick didn't simply murder Edward is an

interesting question. Warwick was apparently

content with the overthrow of the Woodvilles.

Believing that he had secured Edward's submission,

perhaps Warwick . No doubt if Margaret of

Anjou had been involved, Edward would be dead now.

The one thing Elizabeth knew was that Edward would

never be safe as long as Warwick was around.

She was right.

Edward had been released

unharmed in October 1469. At this point,

Edward did not seek to destroy either Warwick or

Clarence. He allowed them to retain their

estates and sought reconciliation instead. In

retrospect, Edward should have listened to his wife

who had suggested destroying both of them for

treason.

Although the king

refrained from punishing the rebels,

he sought to reestablish a

northern counterweight to the Nevilles by restoring the

earldom of Northumberland to the dispossessed heir,

Henry Percy. This turned out to be a

fateful move because it meant depriving John Neville, who had

remained loyal to the king when his brothers rebelled,

of his title, lands and offices.

Edward sought to retain

John's allegiance by compensating him with estates in

the south-west, the new title of Marquess of Montagu,

and the betrothal of his young son George Neville to the

king's eldest daughter and current heir, Elizabeth of

York. George was made Duke of Bedford in recognition of

his future prospects. All this, however, evidently

failed to sufficiently mollify Montagu.

Soon after a private feud

broke out in Lincolnshire between Sir Thomas Burgh

of Gainesville and Lord Welles. Warwick saw

this as an opportunity to lure Edward up north into

a trap. In March 1470, Warwick and George

helped enflame this ongoing skirmish into a serious

problem. Now King Edward was certain to ride

up to the area and restore peace. Edward did

not suspect that Warwick and George would be waiting

for him. Their plan was to ambush Edward and

assassinate him during the ensuing battle, thereby

suffering the same fate as his father had at

Wakefield ten years earlier.

Warwick's plan had bad luck.

Sir Robert Welles, a co-conspirator, gave battle at

Losecoat Field prior to planned trap and was utterly

defeated. He was captured holding documents

that proved the complicity of Warwick and George.

Welles confessed his treason and named Warwick and

George as the 'partners and chief provokers'

of the rebellion. Welles was beheaded, but

Warwick and George were able to flee the country and

go to France.

Warwick was relentless.

He vowed to try again.

|

| |

The Unholy

Alliance

Now an

outlaw, Warwick turned

to Louis XI to see if the French king would help him

mount another rebellion.

Louis XI

had a suggestion for Warwick.

Why not go talk to

Margaret of Anjou??

Margaret

despised Warwick. They had been rivals for

twenty years. How could Margaret forget the

Second Battle of

St Albans? This was the day

she personally

defeated the Yorkist forces of Richard Neville, Earl

of Warwick. Her triumph

rescued her husband Henry

VI being held illegally by Warwick.

With

Louis XI acting as peacemaker, with some difficulty

Warwick showed rare humility and reconciled with

Margaret of Anjou. Both parties reached the

same conclusion... I don't like this person, but the

enemy of my main enemy is my friend.

In

return for the help of Margaret and Louis XI,

Warwick vowed to restore King Henry VI back to the

English throne. Warwick also agreed to marry

his second daughter Anne Neville, 14, to Margaret's

son Edward of Lancaster, 17, to seal the deal.

Louis

was so pleased, he offered to back the next

invasion. Warwick was heard to say, "Louis,

I think this is the start of a wonderful friendship."

Or was it someone else who said that?

|

|

|

The Little Monster

Edward

of Lancaster or Edward of Westminster or Edward V,

whatever, was the only son of Margaret of Anjou.

If Margaret's counterpart on the Game of

Thrones is Cersei, can you guess who

Edward's counterpart on the show might be?

Think about it. I will answer in a moment.

As

presumptive heir to the throne, Edward was literally

Margaret's only reason to carry on. Margaret

had likely committed adultery to conceive him, she

had engaged in endless plots to restore his

birthright, and she now she had done the unthinkable

by accepting help from Warwick, the Devil himself.

Warwick was virtually Edward's last remaining hope

of becoming king of England.

Prince

Edward had been born right in the midst of Richard

of York's surge to power in 1453.

Consequently, Edward's entire life had operated as a

leitmotif for the War of Thrones, or Game of Wars,

whatever. Who could possibly count how many

men had already died so this little kid could keep

hoping to be king someday? Nor was it over.

It was now 1470 and Warwick planned to attack again.

|

|

|

Edward

is none other than Joffrey, definitely the most

hated character on the show (or at least he was

until Ramsey Bolton came along). There was an

incident in Season One where young Joffrey told a

horrible lie. This lie caused the death of an

innocent butcher boy as well as the execution of the

loyal direwolf that had protected Arya from being

stabbed by Joffrey's sword. Watching that

magnificent animal die broke my heart.

It turns

out that Edward was just as vile as his fictional

counterpart. Reports paint Edward of

Westminster as a bad seed, violent and obsessed with

war. There is a well-documented story

that took place at the 1461

Second Battle of

St Albans. In this battle,

Margaret clearly outfoxed Warwick and his brother

Montagu. Soundly beaten, Warwick and Montagu

had no choice but retreat. In the process,

Warwick left behind the bemused King Henry,

who had spent the battle

sitting under a tree, singing.

Two

Yorkists knights,

Lord Bonville and Sir Thomas Kyriell, had sworn to

let their prisoner come to

no harm during the battle.

Even now after the fighting had ended, they

remained beside him

to ensure a safe transfer.

King Henry had promised the two knights

immunity, but Margaret gainsaid him and ordered

their execution.

Margaret

wanted vengeance, so she put the men on trial at which her son presided.

"Fair son",

Margaret asked, "what death shall these

knights die?"

Despite

Henry's desperate

pleas for mercy, Prince

Edward, 8, replied that

their heads should be cut off.

The boy clapped

gleefully as the men suffered their cruel fate.

|

|

| |

|

There is

an interesting footnote to this story. As we

know, what goes around, comes around.

John Neville, aka Montagu,

was also captured

in this battle, but he had been spared

a similar execution.

It turned out he was saved by the Duke of

Somerset, Margaret's main

military advisor. Somerset feared that

his younger brother who was

currently in Yorkist hands might be executed

in reprisal.

Montagu

was forced to watch in horror as these two innocent

men were cruelly put to their death with Margaret

and Edward laughing in the background. This cruelty

left an indelible memory.

Two

years later, Montagu presided over the skirmish

known as the Battle of Hexham. Montagu was

handed thirty leading members of the Lancaster side

following the battle. Recalling Margaret's

vengeance, Montagu executed every one of the men

without hesitation.

|

| |

Third Time is the

Charm

Queen Margaret, our precious Queen

Margaret, in desperate exile in France, running out of money

and lost without soldiers, agreed to an alliance with the

snake Warwick, formerly her greatest

adversary. Amazingly, she let her precious son Edward,

Prince of Wales, marry Warwick’s younger daughter Anne.

The two parents agreed to invade England.

If they were successful, perhaps they could give the

newlyweds a bloodbath for a honeymoon

gift and put

Margaret's son and Warwick

daughter on the throne of England.

Warwick

was getting pretty good at this. First

Warwick staged an

uprising in the north to draw

Edward away from London. Then, with the King

totally fooled and headed north, Warwick and George

came in from behind. They landed at

Dartmouth and Plymouth on 13 September 1470,

picked up a large following in Kent, then headed to

London.

Among the many who flocked

to Warwick's side was his younger

brother John Neville,

known as Montagu.

Montagu had decided to betray Edward.

So what

was Montagu's beef? Montagu had been a

York loyalist for over ten years.

Montagu had fought with his father and brother

Thomas at the Battle of Blore Heath in 1459, and was

captured and imprisoned in Chester Castle by the

Lancastrians, for which he was attainted. That

problem was corrected a year later when John Neville

became Lord Montagu in 1460 thanks to Richard of

York's return to England. Montagu was captured

again at the Second Battle of St Albans in 1461.

Following his second release from imprisonment, he

led the Yorkist forces in the north of England,

defeating the Lancastrians at Hedgeley Moor and

again at Hexham (both 1464).

In reward for driving out the Lancastrians, in 1464,

King Edward IV made Montagu the Earl of

Northumberland, a title which had long been held by

the disgraced Percy family. Montagu was

awarded the Percy estates confiscated after the

Battle of Towton.

However,

when Henry Percy was rehabilitated in 1470, Montagu

was forced to give up the earldom and many important

offices in favor of his former foe. Edward had

felt compelled to do this for fear that troops from

Northumberland would not be loyal. Percy would

keep them in line better Montagu. Montagu was

compensated with other territories, but without

suitable estates or income to support such a

dignity.

Montagu had not taken part

in Warwick's first or second

last rebellion. He

was disappointed when his loyalty to the king had

not been rewarded with the restoration of his

earldom in Norhumberland.

Once a

Neville, always a Neville. Besides, what has

Edward done for me lately? Unbeknownst

to Edward, John Neville, 1st Marquess of

Montagu, decided to switch

to the Lancastrian side.

This time the trap set for

the king worked.

Edward was completely caught out

of position. Once he learned of Warwick's

sneak attack in London, he hurried

back south.

Edward saw Montagu's forces

waiting for him on the road and

let down his guard. Montagu was on his side.

Or was he? Something about the way Montagu's

army approached tipped him

off. Edward realized he would soon be

surrounded. Realizing he

had been betrayed again and that Warwick's

brother Montagu was against him,

Edward headed for the

English Channel as fast as he could. On

2 October Edward fled to

the Netherlands.

The

story of Montagu is interesting because it shows

that Warwick and Edward were so evenly matched that

even one defection could alter the balance of power

in the flicker of a moment.

Back in

England, King

Henry, now 49, was

released from the Tower of London

and restored to the

throne. Henry VI was just as doddering as

ever. He had to be led by the hand when he

paraded through London. He was so frail in

body and feeble of mind, it is unlikely Henry even

knew he was king again. No

matter. Warwick got

what he wanted. Now for the second time, he

acted as the de facto ruler of England in his

capacity as Henry's

lieutenant. At

parliament in November, Warwick

made sure Edward was attainted of his lands

and titles.

The

rebellion had forced the King to flee the country.

Right now things were

looking pretty good for Warwick. George too.

For his loyalty, George

was awarded the Duchy of York.

George was the new Duke of York, just like his

father and brother had once been.

As

anyone who has watched the Game of Thrones

will tell you, treachery can be very profitable.

Apparently it works in reality too.

|

| |

|

Charles the Bold

Charles

the Bold was the mortal enemy of Louis XI, King of

France. Charles held vast amounts of territory

in France, more even than Louis himself.

Charles

was offered the hand of Louis XI's daughter Anne.

The wife he ultimately chose, however, was his

second cousin Margaret of York, sister to Edward IV.

Charles did this in order to ally himself with

Burgundy's old ally England.

Louis XI

had a fit and tried to prevent the marriage with

Margaret. He demanded the Pope refuse to allow

the marriage (the pair were cousins in the 4th

degree), he promised trade favors to the English,

and he undermined Edward's credit with international

bankers to prevent him from paying Margaret's dowry.

Louis

even sent French ships to waylay Margaret as she

sailed to France. Too late. In 1468,

Edward and Charles became good friends as they

celebrated their new alliance over French wine.

|

|

Return of the Jedi

After

being exiled from England, Edward landed in

Flanders, the southern part of Holland, in early October 1470.

He had few men and little money. Edward made

his way to see Charles of Burgundy, his

brother-in-law. Charles greeted him

warmly. Edward was also delighted to

be reunited with Margaret of York, his

favorite sister.

|

|

|

Although Charles

was glad to see Edward, at first he refused to

assist him. Margaret pled Edward's case

to her husband.

She pointed out that Edward's overthrow had considerably

lessened

Margaret's dynastic worth.

This, together with her

regard for her brother who

been cheated of his throne made her plead

passionately that Charles support Edward

and make measures to restore him. It

did no good. Charles held his ground and

paid little attention to

Margaret's begging.

Then

something curious happened. You know how I am

about 'Fate'. Edward

caught a huge break when Louis XI suddenly declared

war on Charles the Bold. After Warwick

completed his overthrow, he sent a message to Louis XI, King of France,

that he would send men to help Louis XI overthrow

Charles of Burgundy,

the hated enemy of Louis.

Louis was really excited. Maybe this overthrow

lightning could strike twice!

Charles was more irritated than threatened.

On a whim, he decided it was in his best

interests to oppose the Lancastrian rule of England,

backed as it was by this

pipsqueak Louis XI. Wouldn't it be fun to give

Warwick and Louis the lesson they deserved?

On

4 January 1471, Charles agreed to

help the

King-in-exile

regain the English throne.

At

last furnished with money, on

14 March 1471, Edward and his youngest brother

Richard landed with a small force at Ravenspur.

Doing their best to avoid detection, Edward first returned

to city of York. Suspicious, York opened its

gates to Edward only after he promised that he had

just come to reclaim his dukedom. This was

literally the same scenario as Henry Bolingbroke had

taken seventy years earlier. Lightning would

indeed strike twice, just not the lightning Louis XI

had hoped for.

Edward

was not about to settle for regaining the Duchy of

York. His ambitions were much larger. As

he marched to London over the next month, Edward

picked up support. The first to join him

were Sir James Harrington and William Parr, who

brought 600 men-at-arms to Edward at Doncaster.

Then someone unexpected joined him.

|

|

| |

|

Coventry

On the

way from York to London, Edward decided to make a

detour to Coventry and challenge Warwick who was

encamped there. Although Warwick's force had

more men than Edward, the earl refused the

challenge. He was waiting for the arrival of

Edward's brother George in order to use their

combined strength to overwhelm the Yorkists.

When

Edward IV learned what Warwick was waiting for,

Edward sent his brother Richard to speak to George.

Six

months earlier,

Edward's brother

George had opposed him during Warwick's successful

third rebellion. After sending Edward fleeing

to France in exile, George was awarded the

Duchy of York for his loyalty,

making him the new Duke of York. Surely that

made George happy. But it didn't. George

was beset with guilt and misgivings.

Previously Warwick

had promised to rebel specifically to put

George on the throne. That failed. The second plot also had

George headed to the throne. That also failed.

Then the objective had changed for the third

rebellion.

George first realized something

was wrong when Warwick had his younger

daughter, Anne Neville, marry Henry VI's son

Edward

of Lancaster

in December 1470.

Currently feeble old Henry VI

was on the

throne, not George. When feeble old Henry did

finally bite the

dust, that would be Margaret's nasty son

Edward taking Henry's place, not George.

Now that George was out of the loop, he realized

Warwick could not have cared less about him.

George

was starting to catch on. George was married

to Isabel Neville and Edward, 17, was recently

married to Anne Neville. If his daughter Anne became Queen

instead of his daughter Isabel, either way Warwick got what he wanted...

one of his two daughters would be the next Queen and the Kingmaker would

be in control.

|

|

| |

|

At this

point, all Warwick wanted from George was more

fighting men. He

realized that his loyalty to

his father-in-law was misplaced.

Aware that his father-in-law was

a lot less interested in making

George

the king than in

serving his own interests,

George realized he had been played.

Meanwhile, Warwick was taking George for granted. Warwick assumed that

George would be satisfied to stay on the Lancaster team

because he was married to Isabel, Warwick's first

daughter, and because he had just been handed the

valuable Duchy of York. Furthermore, through

Isabel, George was currently co-heir to the vast Warwick

estate. Why would George jeopardize his

current land holdings, plus his future inheritance

from Warwick, the richest man in England?

Nevertheless, George felt cheated. There was

no way in hell Warwick would ever put him on the

throne. George had a startling realization...

his fortunes would be better off as brother to the

king than as a nobody under Henry VI and then

eventually Edward of

Lancaster, the new Prince of Wales.

Right

now his younger brother Richard had just asked to

speak to him. George knew what Richard wanted.

He suspected Richard had come to ask George to

return to the House of York. What should he

do? Shakespeare's 'false, fleeting,

perjured Clarence (George)', discontented to now

find himself fighting to maintain the Lancastrian

dynasty, wanted desperately to reinstate himself in

his brother Edward IV's favor. George deserted

his erstwhile ally Warwick, and rejoined his

brother's forces

Reconciled, the three royal brothers moved towards

Coventry. Now George urged Warwick to

surrender. Infuriated with his son-in-law's

treachery, Warwick refused to speak to George.

Edward

was not about to risk attacking Warwick with smaller

numbers, so he turned again towards London. Days

later, when Edward entered London unopposed, George

and Richard were at his side. The old king

greeted his usurper warmly and offered himself into

custody, saying that he trusted Edward. "My

life will be in no danger in Edward's hands."

And with

that, poor old King Henry VI was sent back to the

Tower of London.

|

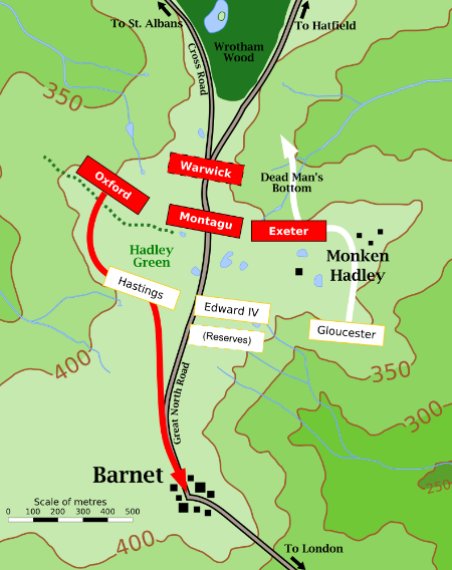

The Battle of Barnet

Warwick

was still fuming over George's last-minute defection

back his brother Edward. Was this a bad omen?

Montagu, Warwick's brother, had once been Edward's

best commander. It had been Montagu's

defection during Warwick's third rebellion that had

turned the tide against Edward in the first place.

Now George was defecting back to his brother's side.

Warwick

dismissed the thought. With George at his

side, Warwick's victory was a slam-dunk certainty.

However, even with the defection, Warwick knew

Edward faced long odds at Barnet, a small town about

12 miles northwest of London. Warwick's army

heavily outnumbered Edward's. Lancastrian

strength ranged around 15,000 men to 10,000 on the

Yorkist side. Furthermore, Warwick had the

advantage of choosing the battleground.

Warwick chose a valley with rolling hills on either

side. In so doing, Warwick wisely chose the

higher ground to the north.

Edward

hurried to meet the Lancastrians hoping to surprise

them. Warwick knew the enemy was near, but

since they arrived in the night was unsure of their

exact location. Edward deployed his trusted

friend Lord Hastings on the left and entrusted his

brother Richard (Gloucester) on the right flank.

Edward

asked George to fight at his side in the center.

He complimented George on his fighting ability as

the reason, but in truth it was easier to keep an

eye on their twice-defected prince there.

As night

fell, Edward put his plan for surprise morning

attack in motion. Under a strict order of silence,

the Yorkist army crept closer to the Lancastrians.

During the night, neither Warwick nor Edward spotted

the opposing army, an event that proved crucial in

the battle the next day.

|

|

| |

|

During

the night, Montagu approached his brother Warwick to

advise him that he felt the troops were skittish.

Montagu suggested that, as the highest-ranking

commanders, he and his brother should fight on foot

throughout the battle instead of riding on horse.

Soldiers believed that mounted commanders tended to

abandon the men when the situation deteriorated.

By staying on foot, the two Nevilles would show

their men that they were prepared to fight to the

death, thus inspiring the troops to stand and fight

harder as well. Warwick agreed and told his aide to

go tether the horses to the rear near Wrotham Wood.

|

| |

|

|

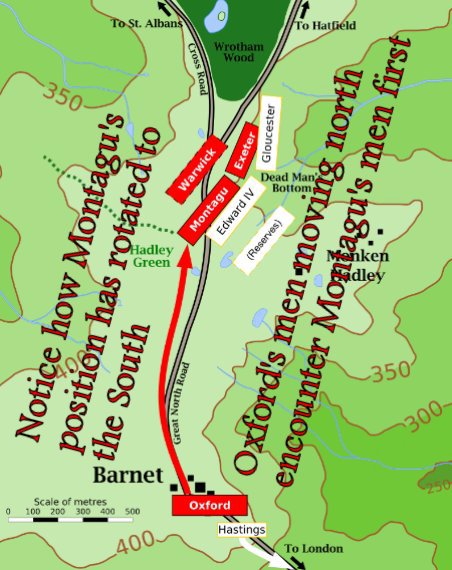

Offset Lines

Two key

things happened in the night.

Warwick

ordered his cannons to continually bombard the

estimated position of the Yorkists' encampment.

This gave Edward the advantage of guessing where the

enemy lie. The Yorkists were able to sneak in

so close that the Lancastrian artillery overshot

their enemies. Meanwhile the York side kept

their cannons quiet and lit no fires so as to avoid

betraying their location.

The

right wing of the Lancastrian army was commanded by

John de Vere, Earl of Oxford. Warwick and

Montagu would command the center which straddled the

road. The Lancastrian left wing was headed by

Henry Holland, Duke of Exeter.

Meanwhile, in the night,

Edward had his brother

Richard, the 18 year old

Duke of Gloucester,

extend his line hundreds

of yards too far to the East. Edward

was unaware that there was no enemy to his front,

just a muddy bog.

What

this meant was the opposing sides were not squared

up. On the western side, Lancaster's Lord

Oxford was up on a hill looking down at the left

flank of York's Lord Hastings. These uneven

lines would prove critical in determining the

outcome of tomorrow's battle.

As the

dawn gave light, the opposing sides realized they

were facing each other like a 3 on 3 basketball

game. Lord Oxford was on the hill opposite

Lord Hastings, the Neville brothers and the

Plantagenet brothers were in the center, but Richard

of Gloucester was way off to the right squared off

against a bog.

These

offset lines would create remarkable consequences

during the battle.

|

|

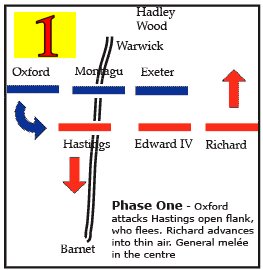

Phase One:

Lord Oxford of Lancaster has the

Upper Hand

|

|

|

|

|

The

moment John de Vere, Lord Oxford (Lancaster), discovered that he

was offset well to the outside of Lord Hastings

(York), he ordered his men to charge down the hill

before the York side could fully realign and defend

themselves properly.

In the

mist, Lord Hastings had no idea he was outflanked by

Oxford. His men were not expecting such a

strong force to attack them. Oxford's

group quickly overwhelmed the men under Lord

Hastings who were caught off guard.

Yorkist soldiers panicked and fled

towards Barnet, chased by the Lancastrians.

As it stood, some of the routed

Hastings' men were so certain of defeat that they

grabbed a horse and kept

fleeing all the way to London twelve miles away.

There they spread tales of the fall of York and a

Lancastrian victory.

The fog

would work a strange magic all day long. If

the skies had been clear, the battle would have

already been over. The horror of seeing

Edward's left line collapse would have caused the

rest of Edward's men to quit on the fight and run

for their lives. Instead, due to the fog,

visibility was low, so the two main forces failed to

notice Oxford's victory over Hastings. Unable

to see what was going on around them to the west,

the opposing center forces continued to fight.

Once

Oxford's group of men reached Barnet, they were now

an entire mile south of the main battle line.

Now this early success turned to disaster when

Oxford's forces began pillaging. Oxford's men lost interest in the battle and split off

in order to begin looting

the fallen enemies. Assuming the battle was

over, many of the men took the time to have a beer

in Barnet and celebrate their victory.

Lord

Oxford was furious at the lack of discipline.

Receiving word from Warwick that he was still

needed, Oxford began yelling and chasing after his men.

It took Oxford two hours to gather

800 men from the original 2,000 and lead them back

up to the battlefield. This unusual U-turn on

the part of Lord Oxford's men combined with the fog

and the offset lines would produce one of the

strangest outcomes ever seen on a battlefield.

|

|

| |

|

|

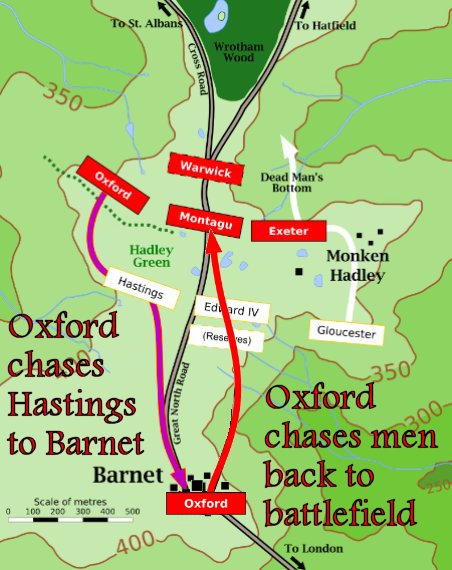

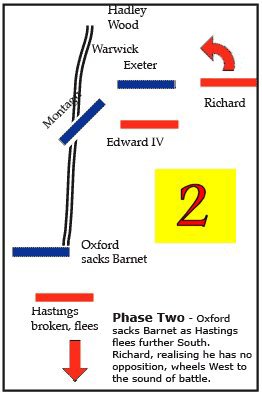

Phase Two: Where is the Enemy?

|

'Fog

of War' is a military term for the uncertainty

experienced by participants in military operations.

Medieval battles were notorious for confusion

because visibility and communication were often

limited.

In the

case of the Battle of Barnet, the Fog of War

took on a different meaning... the morning battlefield was totally

covered in thick mist and fog.

The fog created so much confusion that

the fighting would have appeared almost comical if

it weren't for the fact that brave men were dying on

this day.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

At the

same time as Lord Oxford collapsed the left side of

Edward's line, over on the right, Richard, Duke of

Gloucester, discovered there was no one in front of

him. In the fog, he could not see the enemy in

front. Confused, Richard decided his best

option was to proceed forward and look for Lord

Exeter's forces.

And why

was there no one in front of Richard? On the

previous day, Warwick had the luxury of setting his

positions using the light of the day. Seeing

the swampy ground, Warwick correctly assumed no one

would be stupid enough to attack through the

wetlands. Any attack would be easily repelled

because the mud would bog down the enemy's momentum.

Warwick was pleased... this swamp would guard his

left flank for sure!

While

Oxford's men were busy in town having a beer,

Richard was moving cautiously over on the right near

the Hadley Woods. Although Richard saw the

ground was lowering, he continued forward.

When his men reached the boggy ground, Richard still

could not see the enemy, but he was close enough

that he could hear the sound of battle to the west.

Richard

suddenly realized the fog had given him a huge

advantage. His men could now attack Exeter

from the side coming out of the fog to surprise

them. Richard put his finger to his lips and

whispered... "Silence!"

The men

slowly crossed the boggy ground like invisible

ghosts. They used the sound of the clashing

steel to guide them. Richard's men finally

spotted Lord Exeter's Lancaster men at the edge of a

muddy bog known as Dead Man's Bottom.

For the

past hour, some of Exeter's men had helped fight in

the center, but the majority just stood there

looking for someone to fight. Incredibly,

because their enemy had lined up so far to the

right, the Lancaster wing had no idea Richard's men

were approaching. Suddenly out of the gloom

came 2,000 screaming maniacs running right at them!

The Lancaster men were terrified out of their minds.

|

|

|

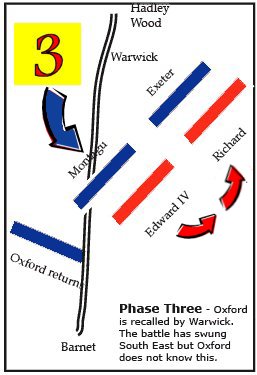

Phase

Three: The Sixty Degree Shift

Seeing Richard suddenly appear from the east

was Lord Exeter's worst nightmare.

Shocked by the mysterious sudden appearance

of the charging enemy, the Lancaster general

did his best to rotate his line sixty

degrees to face the east.

Lord Exeter's bizarre rotation affected the

center. On the York side, Edward was

forced to move to his men to the right to

avoid splitting his forces. The last

thing he wanted was a gap between his men

and Richard's. Edward's movement to

the right completely vacated the Great North

Road. Montagu had no choice but to

give chase to Edward's movement. As

Montagu adjusted his forces, his men

occupied the vacuum on the road. First

they moved to the south, then twisted

towards the east.

The ultimate result of this shift is that

now Montagu's forces occupied the same spot

on the Great North Road where Edward's

forces had once been.

Meanwhile, coming up from the south were

Lord Oxford's 800 reinforcements.

Naturally they used the Great North Road as

the fastest route back. They had been

ordered to attack Edward's men from the

rear, an attack which would have been

crippling under ordinary circumstances.

But these were not

ordinary circumstances.

It

was time for the Fog of War to change the

course of history.

|

|

| |

|

|

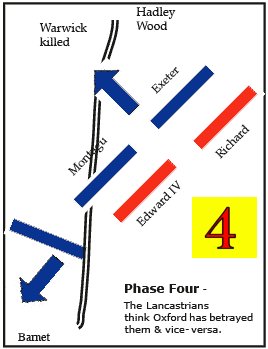

Phase Four:

Betrayal

Think

about this... who did Oxford's men expect to meet on

that road?

They

expected to meet Edwards's men who had started the

day occupying the southern part of that road.

But who

did Oxford's men meet on the road instead?

Montagu's men.

Indeed,

Oxford's ragged band of 800 men met Montagu's men

who had rotated over and taken complete possession

of the road. And did the two Lancaster units

merge to overwhelm Edward? No.

What

happened instead is that Montague's soldiers assumed

Edward's rear guard was coming in from the south to

attack them.

Obscured by the mist , Lord

Oxford's 'star with rays' banner was mistaken

for Edward's 'sun in splendor' banner by

Montagu's soldiers. Without hesitation,

Montagu's archers unleashed a deadly volley of

arrows at their Lancaster comrades.

|

Lord

Oxford's men quickly recognized that they were being

shot at by their own men. Oxford and his men

immediately cried 'Treason!' As staunch

Lancastrians, they knew that Montagu, Warwick's

brother, had previously fought for the York side.

Surely

this unprovoked attack was proof that Montagu had

defected back to the Yorkist cause. Oxford's

men briefly struck back, then decided the best thing

to do was withdraw from the battle. The damage

was done. The shouts of treason were taken up

and spread quickly throughout the Lancastrian line,

breaking it apart as men fled in anger, panic and

confusion.

As the

fog started to dissipate, once Edward saw the

Lancastrian center disintegrate, he sent in his

reserves to hasten the collapse. The Lancaster

leaders began to fall. Although not killed,

Lord Exeter fell first. Amidst the confusion,

Lord Montagu was struck in his back and killed by

one of Oxford's men bent on revenge for the supposed

treachery.

Witnessing the demise of his brother, Warwick fled.

The mighty Warwick was killed fleeing the field in a

desperate attempt to reach his horse. The

Devil was dead, the battle was over.

|

|

|

Margaret

of Anjou had never trusted Warwick. And who

could blame her? Margaret had adopted a wait

and see attitude about Warwick and his Grand

Alliance. Margaret had

been very slow to follow up on Warwick's expulsion

of Edward IV back in October 1470.

Despite

her eight year absence from England, Margaret was

strangely hesitant. She had been asked to

delay her return to England until Warwick had enough

control of the government to satisfy her patron and

backer Louis XI. Six months after Edward's

October overthrow, Margaret lost her patience and

finally got moving. She

sailed for England on 24 March. Uh oh. A

storm came up. Back to France for safety.

Then another storm came up. Back to France for

safety. Slowed by storms, Margaret and Prince

Edward were delayed by two weeks. They landed at Weymouth on 14 April,

Easter Sunday.

Ironically, this was same day that the disastrous Battle of

Barnet was being fought. Perhaps if Margaret's

forces had been at Warwick's side at Barnet, the

outcome would have been much different. Who

can say?

So why

wasn't Margaret at Warwick's side?

Keep in

mind that communication was very slow in those days.

Although Margaret had received the promising report

that Warwick was now running the government in

England, she had not received the reports that

Edward had landed on the English coast on 14 March.

Those same storms which prevented Margaret from

leaving France also prevented ships from landing in

France to give her the updated information on

Edward's new threat. If she had known of

Edward's threat to Warwick, she would have headed

directly for London with her army instead of landing

two hundred miles away in Weymouth.

While

Margaret sheltered at Cerne Abbey near Weymouth, the

Duke of Somerset, Edmund Beaufort, brought news of

the disaster at Barnet to her. What a blow it

must have been for Margaret to discover Warwick's

demise. Margaret

immediately wanted to leave and head back for the

safety of France. Edmund Beaufort suggested they stay

and fight. Now that Warwick had fallen,

Beaufort pointed out they might not get another

chance like this. This moment carried the

sense of 'Last Shot'.

Edmund

Beaufort, 33, was the new commander of Margaret's

army. Edmund was the son of Margaret's

one-time lover

Edmund Beaufort, the man who had died at the First

Battle of St. Albans back in 1955. Edmund was

also the

brother of Henry Beaufort who had commanded the

Lancastrian forces for nine years following his

father's death. Henry had died at the

Battle of Hexham in 1464. Now it was the

junior Edmund's turn to run the show along with his

younger brother John Beaufort. One can only

wonder if either son knew that their deceased father was

also the likely father of Margaret's son Edward.

In other words, Prince Edward was likely their

half-brother.

Sometimes the truth is stranger than fiction.

| |

|

So what

should Margaret do? Margaret

dearly wished to return to France, but her commander

said that if they could join up with the powerful army

waiting for them in Wales, they had an excellent

chance of unseating Edward IV themselves.

Margaret turned to her 17-year-old son Edward and

asked him what he wanted to do.

Prince Edward

persuaded his mother to gamble for victory.

They had landed in Lancaster country. Somerset

and the Earl of Devon had already raised an army for

Lancaster here in the countryside of west England.

Their best hope was to march northwards and join

forces with the Lancastrians in Wales. And

with that, Margaret was persuaded.

In

London, King Edward learned of Margaret's landing.

Realizing the She-devil was loose in the west, Edward moved swiftly to meet her. However he

was unsure of her destination. As it turns

out, Wales was equidistant for both parties 125

miles away. The advantage was on Margaret's

side because she knew where she was going and Edward

didn't. However, Edward's advantage was that

at first Margaret did not know he was chasing her,

so she took her sweet time getting there.

The race to

Wales was on.

|

|

| |

|

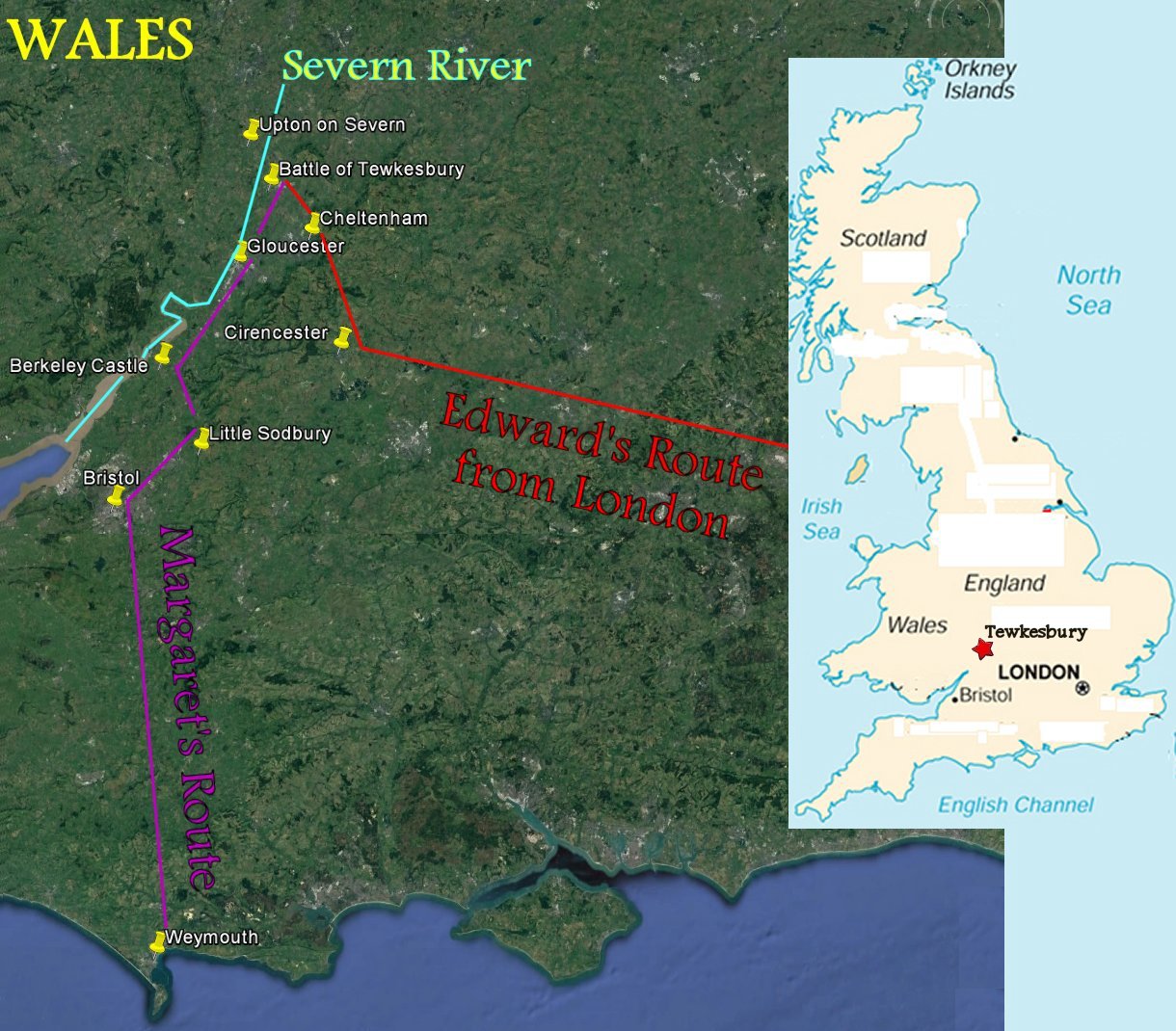

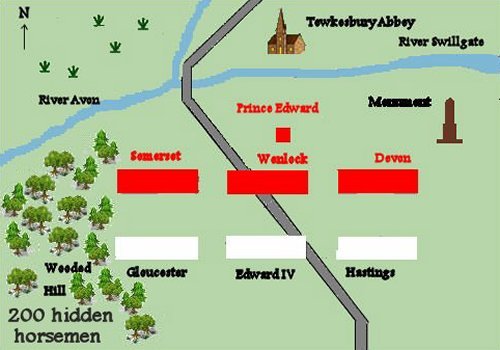

By 30

April, Margaret's army had reached Bristol

on its way towards Wales. On the same

day, King Edward reached Cirencester,

just 30 miles northeast of Margaret's position.

On hearing that Margaret was at Bristol, he turned

south to meet her army. However, the Lancastrians

made a feint towards Little Sodbury,

halfway between Bristol and Cirencester.

Nearby was Sodbury Hill, an Iron Age hill fort which

was an obvious strategic point for the Lancastrians

to seize. When Yorkist scouts reached the hill,

there was a sharp fight in which they suffered heavy

casualties. Believing that the Lancastrians were

about to offer battle, Edward temporarily halted his

army while the stragglers caught up and the

remainder could rest after their rapid march from

Windsor.

And with

that, Margaret's trick had worked. With Edward

preoccupied with her Sodbury Hill diversion, she was

able to sneak away. The Lancastrians instead

made a swift move north by night, passing undetected

within 3 miles of Edward's army. By the

morning of 2 May, they had gained the safety of

Berkeley Castle and had a head start of

15 miles over Edward in the race to the bridge at

Gloucester.

Now King Edward guessed what Margaret was up to.

No doubt the Lancastrians were seeking to cross the

River Severn into Wales. The nearest

river crossing point they could use was at the city

of Gloucester. Edward sent his

horsemen to deliver an urgent message to Sir

Richard Beauchamp, the Governor, ordering him to bar

the gates to Margaret and man the city's defenses.

This was a critical move.

Beauchamp's father

had been a Lancaster. What should he do?

Defy his king and let Margaret through? If he

told Margaret 'no', then he risked having her

attack his city. Given the mood she was in,

this was a real possibility. Why not let her

through and avoid the bloodshed?

Then it

occurred to Beauchamp that he would