| |

Rick Archer's Note:

If you would like to read the

story of how a Lowly Servant Bedded a Queen and

started a Dynasty, there are two places to begin.

The place I recommend you

start is with 'The Madness

of King Charles'.

Or you can go straight to the

juicy stuff and visit 'How

a Lowly Welshman Bedded a Queen and Sired A Dynasty'.

However, I don't recommend the

shortcut. This story is so complicated that

you really do need the background information in

order to follow the bouncing ball.

|

| |

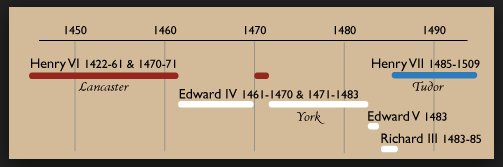

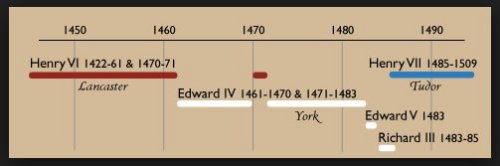

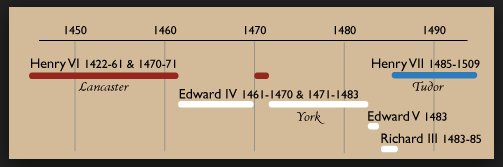

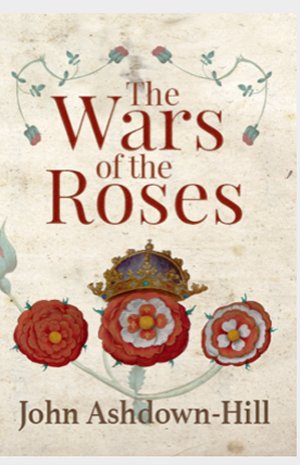

The War of the Roses

ACT THREE:

Richard III

|

| |

|

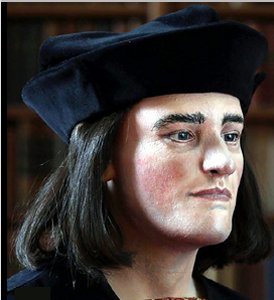

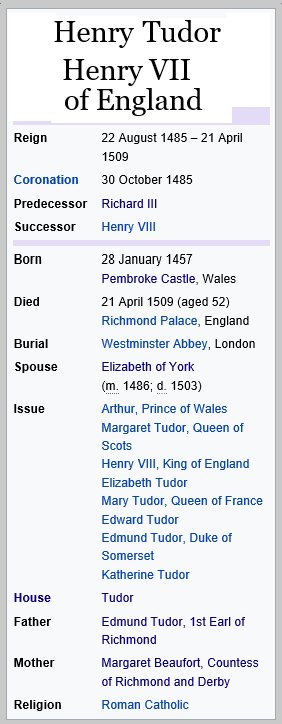

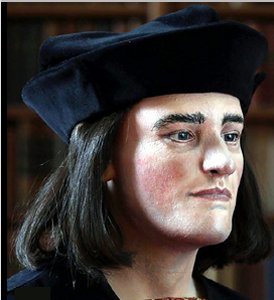

The star

of Third Act in the War of the Roses is none other

than Richard III. And who might be Richard the

Third? We know

Richard better as Edward IV's younger brother

Richard, the Duke of Gloucester.

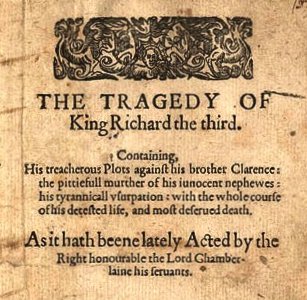

Richard

the Third made a lot of enemies, but his worst enemy

was William Shakespeare. William

Shakespeare had a field day at Richard's expense with

Richard III, considered one of The

Bard's ten

best plays.

Before

Shakespeare was finished, Richard had murdered Henry

VI, his brother George, his nephews, and even his

own wife during his well-plotted ascent to the

throne. In case these heinous murders were

insufficient clues, Shakespeare dressed Richard in

black and accentuated his a hunchback to emphasize

who the villain was.

|

|

|

Anne Neville

Following Prince Edward's death at Tewkesbury, his

wife Anne Neville became the grand prize.

Anne

Neville was born into the wealthiest and most

politically powerful family in the kingdom. Youngest

daughter of the Earl of Warwick, Anne watched her

father make a king out of Edward of the House of

York, and then change his alliance to the House of

Lancaster. Anne, raised a York, was expected

to change her loyalties as well.

In 1470, Anne had been the trophy dangled by her

father Warwick to secure the backing of Margaret of

Anjou in the newest attempt to overthrow King Edward

IV. During the desperate race to reach Wales,

Anne chose to stay with the army. She marched

with them for more than a hundred miles, from

Weymouth to Tewkesbury where Edward’s pursuing army

caught them, killing Prince Edward and capturing

Margaret of Anjou.

Anne was a widow at 15, far too wealthy and powerful

to be left to chance. Her sister Isabel, now a loyal

supporter of the House of York thanks her

side-switching

husband George, scooped up the girl and took her

into their keeping. Isabel swore she was

protecting Anne, but in reality this was more likely a form of

house arrest.

Anne became the subject of

dispute between George, Duke

of Clarence, and his brother Richard,

Duke of Gloucester, who

had stated to George his desire to marry her.

Anne and her sister

Isabel, George's wife, were heiresses to

their parents' vast estates. George

was anxious to secure the

combined inheritance of

both sisters! George thereby treated

Anne as his ward and

opposed her getting married.

Strange stories ensued. One wild tale had

George hiding Anne in a London

diner, disguised as a

servant, so that his brother would not know where

she was.

Nonetheless, Richard

Gloucester tracked her down

and escorted her for safekeeping

at the Church of St Martin le Grand

out of George's reach. In order to win

the final consent of his brother George to the

marriage, Richard renounced most of Warwick’s land

and property, including the earldoms of Warwick

(which the earl had held in his wife’s right) and

Salisbury and surrendered to

George the office of Great Chamberlain of

England. It was a high

price to pay.

|

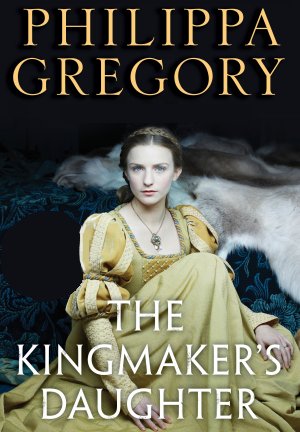

In this

passage from The Kingmaker's Daughter,

Anne Neville is talking to herself shortly after the

fall of Tewkesbury:

One of the

guards

has stumbled while mounting his horse.

Frightened, his horse shies

away, knocking the horseman

to the ground. Seeing

the horse rear, King Edward puts his arm

around his wife in an unconscious

gesture to protect her. Everyone

is looking that way.

I snatch off my glove

and, in one swift gesture, I throw it towards

Richard. He catches

it out of the air and tucks it in the breast of his

jacket. Nobody has

seen it. Nobody

knows.

The guardsman steadies

his horse, mounts it, and

nods his apology to his captain.

The royal family turns

and waves to us.

Richard looks at me,

buttoning the front of his jacket, and smiles at me

warmly, assuredly, to denote he

understands the meaning of my gesture.

Richard

has my glove, my favor. It is a pledge that I

have given in the full knowledge of what I am doing.

Because I

never want

to be anybody’s pawn again.

Philippa Gregory, The

Kingmaker's Daughter

|

|

| |

|

The Strange Saga

of George

So what

exactly did Shakespeare mean by the immortal line 'false,

fleeting, perjur'd Clarence, that

stabbed me in the field by Tewksbury!'

Shakespeare was referring to the ghost of Edward,

Prince of Wales, stabbed to death in cold blood

following the Battle of Tewkesbury.

George, better known as 'Clarence',

is dreaming of

the evils he has

done

during his fitful sleep preceding

his imminent execution.

|

|

|

|

Following Warwick's death in

the 1471

Battle of Barnet, George, Duke of

Clarence, was consumed by

a serious overdose of greed. Married to

Isabel, one of Warwick's two daughters, George went

ahead and confiscated the vast estates of the

earl. George had been be a

very bad boy. He

had betrayed his brother Edward. Later

he betrayed Warwick, his father-in-law. In

George's case, cheating had been profitable.

In March 1472 by right of

his wife Isabel, George became the

Earl of Warwick and Salisbury.

George was now rich beyond his wildest imagination.

Nevertheless, he was greatly disturbed when

he heard that his younger brother Richard was

seeking to marry Warwick's younger daughter Anne,

Isabel's sister.

George was upset because Richard was

also claiming some part of Warwick's lands

as part of the wedding package.

George refused to part with

a single nickle, so a violent quarrel

between the brothers ensued.

After George failed to prevent

Richard from

marrying Anne, the quarrel grew

worse. Finally, in 1474

King Edward had to step in to

settle the dispute, dividing the estates between his

brothers. [It must be tough

being rich, but then I wouldn't know.]

In

December 1476, George's wife Isabel

died two months after

giving birth to a short-lived son named Richard.

Though Isabel's death was likely the result of

either consumption or childbed fever, George was

convinced she had been poisoned by Ankarette, one of

her ladies-in-waiting, operating in cahoots with his

enemy Elizabeth Woodville. George alleged that

King Edward’s wife was guilty of

witchcraft in this matter. Try to imagine how

well that sat with King Edward.

George bullied a

jury into convicting Ankarette of murder by

poisoning, then had her hanged immediately after

trial. Clarence's mental state, never stable

to begin with,

deteriorated from that point on.

|

|

In 1477

George

became a

suitor for the hand of

Mary,

daughter of Charles the

Bold. Mary was

quite the catch, being

extremely beautiful and

possessing vast estates.

She was better known by

her nickname,

'Mary the Rich'.

George wanted to marry

the rich.

Unfortunately for

George, King

Edward

objected to the match.

Clarence,

assuming his jealous

brother Richard was

behind this slight,

left the court

fuming.

George was not getting

along with Edward well

at all. In

addition to

belligerently accusing

Edward's wife of

murdering Isabel, not

long after her death of

Isabel, men

who were in the employ

of George were caught

plotting against the

King. The timing

was very unfortunate.

It seemed like George

was trying to get

revenge of some sort.

There's an old saying, 'Once

a cheater, always a

cheater'.

George had crossed the

line one time too many.

Edward had forgiven the

man once before; he wasn't

going to make that

mistake again.

Edward had the

duke thrown into prison,

then

unfolded the

charges

to the

parliament...

George had

slandered the king; had

received oaths of

allegiance to himself;

and

was

preparing for a new

rebellion.

In short, George was

bad.

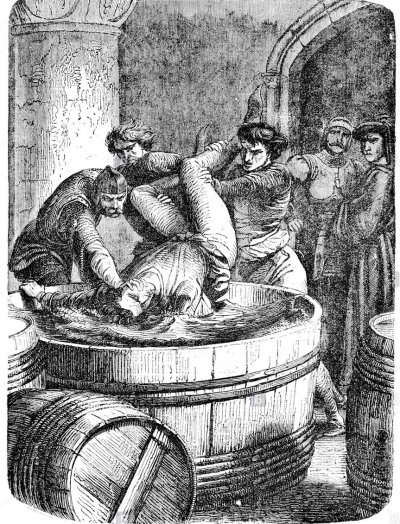

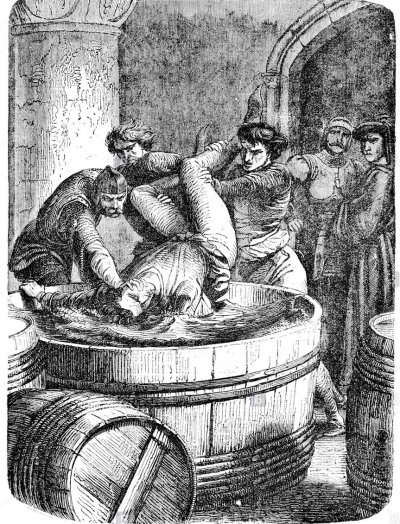

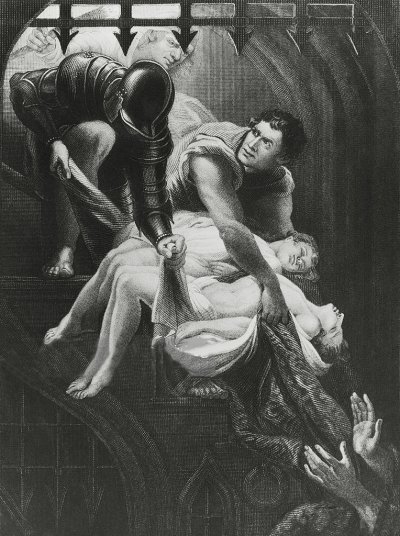

George was executed 'in

private'.

In his play, Shakespeare

gave Richard the blame,

but history suggests

Richard had nothing to

do with it.

Following George's

death, there

was a strong

rumor that

George had been

drowned in a

cask

of malmsey wine.

The headsman does

it, leaving his axe to

one side but wearing

his black mask over his

face. He is a big man

with strong big

hands and he takes his

apprentice with him.

The

two of them roll

a barrel of malmsey wine

into George’s room and

George the fool makes a

joke of it and laughs

with his mouth open wide

as if already gasping

for air, as his face

bleaches white with

fear.

Philippa Gregory, The

White Queen

|

|

Long Live the

King... or maybe not

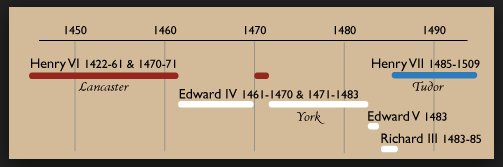

Following Tewkesbury, there were twelve years of

peace in the land. With the Lancastrian

line virtually extinguished, Edward faced

no more rebellions after his restoration.

Edward and

his wife Elizabeth had been through a lot.

Amazingly, Elizabeth had kept the children safe

while Edward was constantly fighting to keep his

throne or regain his throne. Three of his

children would figure prominently in Act Three.

•

Elizabeth

of York (1406-1503)

•

Mary

of York (1467-1482)

•

Cecily

of York (1469 – 1507)

•

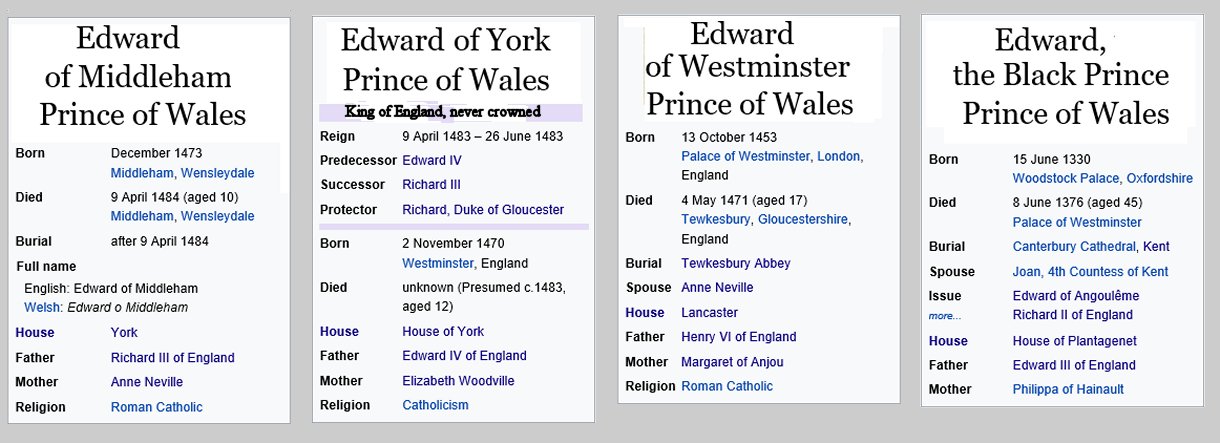

Edward

V of England (1470 – 1483)

•

Margaret

of York (10 April 1472 – 11 December 1472).

•

Richard

of Shrewsbury

(1473 – 1483)

•

Anne

of York (1475 – 1511)

•

George

Plantagenet (1477 – 1479).

•

Catherine

of York (1479 – 1527)

•

Bridget

of York (1480 – 1517)

Tragically, Edward died

unexpectedly after a short illness on 9 April 1483.

Everyone was in shock.

There

would never have been an Act III to the War of the

Roses if Edward had reigned just a bit longer.

Unfortunately, Edward's untimely death in 1483 would

reignite the War of the Roses. In the

picture, dark-haired Richard stands at King Edward's

side. How fitting that Richard III would

become the villain of Act III.

|

|

|

Richard's

Treachery

When

King Edward's health began to fail,

at least he had sufficient time to put his affairs

in order. Edward was comforted by the

knowledge that the ever-present issue of succession

was not a problem. Elizabeth had given birth

to two healthy, handsome, well-educated boys,

Edward, 12, and Richard, 10.

Edward

smartly named Richard, his trusted brother, as

protector of his two sons. On second thought,

maybe not so smart.

On the

death of Edward IV, on 9 April 1483, his

twelve-year-old son, Edward V, succeeded him while

Richard, the current Duke of Gloucester, was named Lord Protector of the Realm.

Richard moved swiftly and secretly to prevent the

Dowager Queen Elizabeth from exercising power.

Richard

left his base in Yorkshire for London. On 29

April, as previously agreed, Richard was joined on

the route by his cousin the Duke of Buckingham.

They met Anthony Woodville, the Dowager Queen

Elizabeth's brother at Northampton.

Anthony

Woodville was escorting young Edward at the Queen's

request to London with an armed escort of 2000 men.

Richard and Buckingham's joint escort was of 600

men. The

young king was not there. He had been sent further south to

Stony Stratford.

Richard

politely invited Anthony Woodville, his nephew

Richard Grey (son of Elizabeth by a prior marriage),

and Thomas Vaughan to dinner. After the meal,

they were suddenly arrested on the charge of treason

against the Lord Protector. On June 25, they

faced a tribunal led by Henry Percy, 4th Earl of

Northumberland. The three men were found

guilty and executed.

After having Lord Rivers (Woodville) arrested, the two dukes

moved to Stony Stratford where Richard falsely

informed the young king of a plot aimed at denying

him his role as Protector, adding that the 'perpetrators'

had been dealt with. Richard proceeded to

escort the young king to London on 4 May.

Richard

suggested to the boy that he would be the safest and

most comfortable in the Royal Apartments of the

Tower of London where kings customarily awaited

their coronation. The young Prince thought he

was a guest, but in reality he was a prisoner.

|

| |

Queen Elizabeth and

Lord Hastings

|

|

|

|

After

the unexpected death of Edward IV on 9 April 1483,

the dowager queen knew there could be trouble.

She sought to monopolize political power for her

family by appointing family members to key

positions. She also tried to circumvent

Richard, 31, Edward's younger brother, by rushing

the coronation of her young son Edward V, 12, as

king.

Lord

Hastings was probably the most loyal friend Edward

IV ever had. By all accounts, Hastings had

also been friendly with Richard. Conversely,

Lord Hastings was hostile to the Woodville family.

The Woodville family was not popular with many due

to their quest for wealth and power. Desiring

to frustrate the ambitions of the Woodvilles, Lord

Hastings turned to the new king's uncle - Richard,

Duke of Gloucester, brother of Edward IV.

Hastings

checked Elizabeth's maneuvers and kept Richard

informed of her actions. Alerted by Hastings,

Richard intercepted the young king and his Woodville

relatives as they made their way to London i April

1483.

Hastings

now supported Richard's formal installation as Lord

Protector and collaborated with him in the royal

council. In other words, Hastings had been

instrumental in helping Richard try to grab the

throne for himself. On the other hand, no one

knows how he felt about Edward V being held captive.

Affairs changed dramatically on 13 June 1483.

During a council meeting at the Tower of London,

Richard, supported by the Duke of Buckingham,

suddenly accused Hastings and two other council

members of having committed treason by conspiring

against his life with the Woodvilles. While

the other alleged conspirators were imprisoned, Lord

Hastings was immediately beheaded on Richard's

orders over a log in the courtyard of the Tower.

There was no trial.

The execution of the popular Hastings remains

controversial to this day. No strong evidence

of a 'Hastings conspiracy' has ever surfaced.

|

|

| |

|

Rick Archer's Note: Susan Higginbotham

(source)

is the author of five historical novels about

medieval England. I have taken excerpts from

her excellent article on Lord Hastings.

As with so much involving Richard III, there are

conflicting theories as to why William Hastings

met his death at the hands of Richard, Edward

IV’s supposedly devoted brother. Richard

himself claimed that Hastings had been plotting

against him, though he never produced any

proof to substantiate his claims.

Those defenders of Richard who have taken him at

his word suggest that Hastings was driven into

conspiracy by concerns that under the

protectorate, he would lose the power and

prestige he had enjoyed during Edward IV’s reign

or by his suspicion that Richard meant to take

the throne for himself.

The alternative explanation is that there was no

plot at all and that Richard, having planned to

seize the crown, ruthlessly eliminated Lord

Hastings as the man most likely to stand in his

way.

It is probably not a big surprise to readers of

this blog that I lean toward the second theory:

that of there being no plot by Hastings at all.

Richard had recently had three of the men

closest to Edward V—his uncle Anthony Woodville,

his half-brother Richard Grey, and his

chamberlain, Thomas Vaughan—arrested on equally

vague charges of conspiracy, which would never

be proven. They too would be executed

without trial.

Soon came the lies about the legitimacy of the

Woodville children. Richard and his

followers preached the story that Edward IV had

been pre-contracted to a woman named Eleanor

Butler before his marriage to Elizabeth

Woodville. This, in their opinion, made the latter marriage invalid

and the resulting children bastards.

Therefore Richard was the rightful king, not

Edward V (sitting in the Tower of London) or his

brother Richard (also sitting in the Tower).

The English Council agreed and Richard was

crowned King.

These

trumped-up allegations would never see the inside of an

ecclesiastical court, where they belonged.

In each case—Hastings, Woodville, Grey, Vaughan,

and the precontract—Richard would accuse, but

never prove. None of those involved were allowed

to defend themselves against Richard’s

allegations.

Woodville, Grey, and Vaughan were languishing in

prison at Pontrefact Castle when Hastings was

beheaded on 13 June. Their execution would

come 12 days later. Therefore, Hastings

was the first head to roll.

If Hastings could be assassinated in cold blood,

then anyone could be assassinated. Given

the immediate danger to the life of anyone who

spoke up, no one dared to press the point.

During Richard's coup d'état, the list was long and quite intimidating:

•

The

sudden, shocking execution of Hastings

•

The

trumped-up allegations concerning the illegitimacy of

Edward's children

•

The

arrests of others on June 13 and on June 14

(including the Archbishop of York, the Bishop of

Ely, Oliver King, secretary to Edward V, and

John Forster, an official of the queen)

•

The

previous arrests of Edward V’s associates

Woodville, Grey, and Vaughan and

their executions on June 25

•

The

large number of armed men sent to Westminster

Abbey to 'persuade' Elizabeth Woodville

to give up the Duke of York to Richard on June

16

•

The

rumors of massive numbers of troops headed from

the north, Richard's power base, to London

These were powerful incentives for those who

valued their heads to be docile, for the time

being at least. What must have made

Hastings’ execution all the more terrifying was

that he was no unpopular royal favorite, but

rather a

well liked, competent, and respected man who had

been associated with the Yorkist cause for

decades.

If Hastings could be assassinated in cold blood,

then anyone could be assassinated. Given

the immediate danger to the life of anyone who

spoke up, no one was safe. Consequently

there was little protest. Richard had

everyone cowered.

Susan Higginbotham

(original

source)

Two associated comments:

Laura says:

June 13, 2011 at 5:28 am

I find it heart-rending that Hastings' death

came at the hands of a man that he had eaten

and drank with, fought and bled beside.

Richard wanted Hastings out of the way

because he knew Hastings was the one person who

had the power and the strength of character

to stand up to his ambition. There is no

excuse for cold-blooded murder, yet that is

what Richard committed that day by refusing

Hastings the opportunity to exonerate

himself of those charges. Despite the fact

that Richard had other redeeming features,

that unjustified act stands out in my mind

as a defining moment for him. He preferred

the death of a loyal and trusted friend and

ally to his own greed and ambition.

Susan Higginbotham says:

June 13, 2011 at 7:43 am

Thanks, Laura! I quite agree. Even if

Hastings were actually plotting against

Richard, he could have been sent to the

Tower and given a trial. His hasty execution

suggests to me that Richard not only

regarded him as a threat to his ambitions,

but that he also knew that Hastings could

and would give evidence against the

existence of a precontract if left alive to

do so.

|

The Princes in the

Tower

|

|

|

|

Upon

hearing the news of her brother

Anthony's arrest, the Dowager Queen

knew Richard had betrayed her. Sensing she was

in great danger, Elizabeth fled to sanctuary

in Westminster Abbey together with her son by her

first marriage, her five

daughters, and her

other son Richard, Duke of

York.

On 16 June

s large number of armed

men were sent to 'persuade'

Elizabeth Woodville to give

up the Duke of York to Richard.

Elizabeth

Woodville was told to hand over the younger prince

Richard to the Archbishop of Canterbury so

that the

boy might attend his brother Edward's

coronation. She should have

never trusted these men. Richard was immediately

placed with his older brother Edward in the Tower of

London. After

that, things

went from very bad to much worse.

|

|

|

|

|

One day

before the scheduled coronation of young Edward,

Bishop Stillington of Bath and Wells announced that

the children of King Edward and his Queen, Elizabeth

Woodville, were illegitimate. Stillington

charged that before Edward IV married Elizabeth,

Edward had entered into a precontract for marriage

with another woman, Eleanor Butler.

This

action rendered the King’s marriage to Elizabeth

Woodville invalid. Thus, Prince Edward would

have been a bastard and ineligible to ascend to the

throne (and his brother as well).

On 22

June 1483, a sermon was preached outside Old St.

Paul's Cathedral declaring Edward's children

bastards and Richard the rightful king. Shortly

after, the citizens of London, both nobles and

commons, convened and drew up a petition asking

Richard to assume the throne.

This is

what Richard had hoped for. He was now legally

able to assume the crown. On 25 June, an

assembly of Lords and Commons declared Richard to be

the legitimate king.

Meanwhile, the two princes remained in the royal

apartments in the Tower of London. Sometime in late

summer or early fall of 1483, the boys disappeared

from view; there is no record of their having been

seen again. At the time the Princes vanished,

Richard and his new Queen were on “progress” in the

north of England, hundreds of miles from London.

|

A Footnote to History

Richard

was crowned as the new King of England on July 6.

The reign of King Richard the Third had begun.

Long live the King!! Or maybe not.

Two years later he would be dead.

Had

Richard not betrayed his nephews, there is every

possibility the York dynasty would have survived.

However, Richard’s own future would have been quite

difficult. Richard was despised by Elizabeth

Woodville and all of her relatives at court.

He would surely become the focus of Woodville

discontent. Edward V, the boy king, would have

followed his mother’s wishes when he came of age.

The boy had, after all, been raised and tutored by

his Woodville relations and hardly knew Richard.

No doubt Richard would have become a footnote to

history just like his brother George, the Duke of

Clarence. Richard was too ambitious to let

that happen. The boys had to go.

|

|

|

|

Indeed,

the two boys were never seen in public again.

The fate of Edward and his brother Richard remains

unknown to this day. The most widely accepted

theory is they were murdered on the orders of their

uncle, King Richard. Thomas More wrote the

princes were smothered to death with their pillows.

His account forms the basis of William Shakespeare's

Richard III, in which Richard orders

Tyrrell to murder the princes.

Since

there is no proof of what really happened, many

different theories have surfaced over the years.

However, these competing theories are nowhere near as

plausible as the straightforward one pointing to

Richard. Richard controlled access to the

boys, Richard was responsible for their welfare, and

Richard is the one who stood to gain the most by

their murder. Furthermore, if someone else was

responsible for their deaths, why didn't Richard cry

foul at the top of his lungs and conduct a public

investigation?

Guilty? Most people think

so, especially after seeing Shakespeare's Richard III.

Bones belonging to two children were discovered in

1674 by workmen rebuilding a stairway in the Tower.

On the orders of King Charles II, these were

subsequently placed in Westminster Abbey, in an urn

bearing the names of Edward and Richard. The

bones were reexamined in 1933 at which time it was

discovered the skeletons were incomplete and had

been interred with animal bones. It has never been

proven that the bones belonged to the princes, and

it is possible that they were buried before the

reconstruction of that part of the Tower of London.

Permission for a subsequent examination has been

refused.

In 1789, workmen carrying out repairs in St George's

Chapel, Windsor, rediscovered and accidentally broke

into the vault of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville.

Adjoining this was another vault, which was found to

contain the coffins of two children. This tomb was

inscribed with the names of two of Edward IV's

children: George, 1st Duke of Bedford, who had died

at the age of 2; and Mary of York who had died at

the age of 14. Both had died before the King.

However, the remains of these two children were

later found elsewhere in the chapel, leaving the

occupants of the children's coffins within the tomb

unknown.

|

|

| |

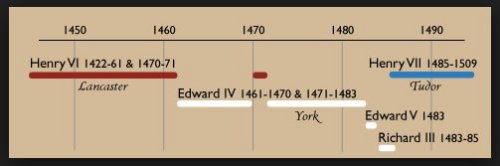

Biographies

Transitions were

always perilous times in Medieval England.

Power-hungry people viewed transitions as

opportunities to exploit the leadership vacuum to

advance their own ambitions.

Keep in

mind that the War of the Roses spanned over thirty

years. Following the 1471 Battle of

Tewkesbury, King Edward IV ruled unopposed for

twelve years.

During

that time, an entire new generation of faces moved

into position. So let us detour from the

treachery of Richard and learn more about the

background stories that make Act III: Richard

III so compelling.

|

|

The Madness of King

Charles

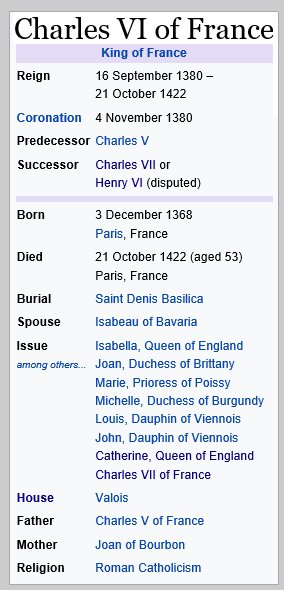

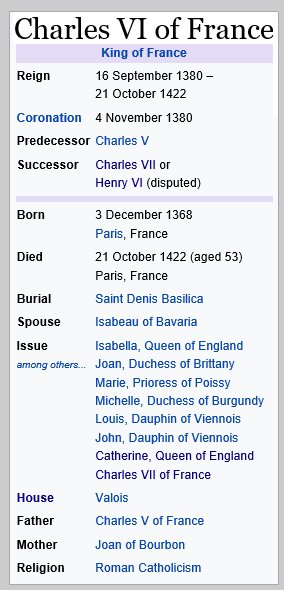

Charles

VI was better known as Mad King Charles.

The best

known story about Charles took place in 1392.

Charles was 24. In April, Charles suffered

from a mysterious illness which caused his hair and

nails to fall out. That summer, Charles was

hardly recovered. He still suffered from

occasional bouts of fever and behaved incoherently

at times. One day Charles and his men set out

on an expedition. One of his advisors had

barely survived an assassination attempt. Now

Charles went looking for the fugitive assassin.

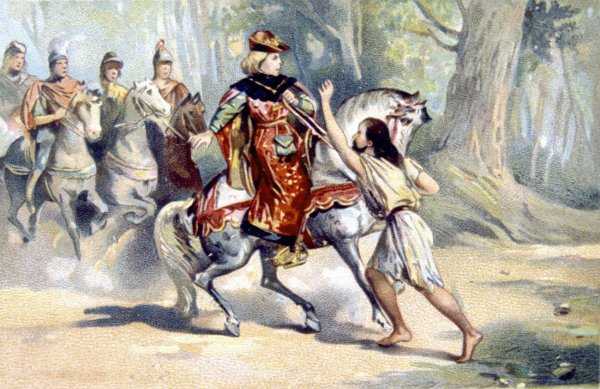

On a hot

day in August, Charles was riding through the forest

at the head of a group of knights when a

wild-looking man ran up to his horse and spoke some

words of doom and betrayal.

The

soldiers chased the man away, but Charles' nerves

were clearly disturbed. Charles absolutely

freaked out.

|

|

|

Leaving

the man behind,

the group continued their

journey. Soon after, a page accidentally

dropped a lance. Charles flipped out.

Without warning, he rushed forward with a drawn

sword and killed four of his men. The astonished

victims did not even defend themselves, assuming the

king had the right to kill them if he wanted to.

Finally

the others overcame their shock and overpowered the

king. Lifted from his horse, Charles lay flat

and speechless on the ground, his eyes rolling

wildly from side to side. His attendants found

an ox-cart to carry him. For two days Charles

was in a coma. When Charles heard that he had

killed four of his own men, he wept.

From

then on his mental health was seriously undermined.

Charles would go through

episodes of forgetting people's names, including his

own, and the fact that he was king. Occasionally he

would run through his castle howling at people; he

was pretending to be a wolf. When his spells

were upon him, he would sit in a room, motionless,

for hours. If he did move, he did so with extreme

caution. Questioned about this, he claimed

that he was made of glass, and one wrong move would

shatter him.

Charles

suffered from severe schizophrenia.

Mental illness ran

rampant in the family. Desperately ill, he was

delusional. At times he believed his enemies were

upon him and would be thrashing and fighting off the

invisible foes. But King Charles was not the only

one in the family who was mad. His

mother, Joan of Bourbon was unbalanced.

She became totally deranged after giving

birth to her seventh child. Her father, uncles, and

grandfather also suffered mental maladies.

|

| |

The

problem with having a Mad King is the fact that the

Kingdom of France depended on him.

Charles became king of France in 1380 when he was

12. He ruled for 42 years till his death in

1422. All 42 years took place during the worst

part of the Hundred Years' War with England. Yes, the same

hundred years when England plundered and humiliated

France time and time again. Was Charles was part of

the problem? Well, what do you think?

When

your country is fighting something called the 'Hundred

Years' War', it's really unfortunate if the man

sitting on the throne is nicknamed 'Mad King

Charles'... unless of course it means he's

really angry at someone. No, he was just nuts.

The

question the reader might be asking is why I am

discussing a French King who died 60 years before

Richard the Third became king of England.

There are two things the English people are very

squeamish about in regards to their kings... illegitimacy

and madness.

There

have definitely been English kings who were crazy.

Mad King George III comes to mind. His madness

led directly to a certain well-known war known as

the American Revolution. This madness stuff in

a king can be incredibly costly to a nation.

So now I

have question. This has

been a very long and quite complicated story, but can you remember

WHO was

most responsible for creating the War of the Roses?

Let's see if you

get it

right. Scroll down.

|

|

|

|

Keep

scrolling.

|

|

|

A Very

Naughty Girl

|

|

|

|

|

|

Did you answer Richard, Duke of

York? Close, but he's not the best answer.

Did you

answer Margaret of Anjou? Closer, but she's

not the answer either.

Did you

answer French King Charles the Sixth?

You're getting warmer.

The

madness of Charles VI let England have its way with

France for half a century. Thanks in large

part to the cruelty of England's Black Prince, countless

men were murdered, women were raped, fields

were burned, and townships were pillaged and leveled.

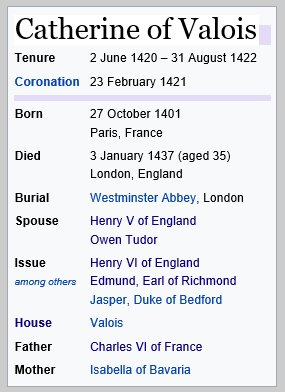

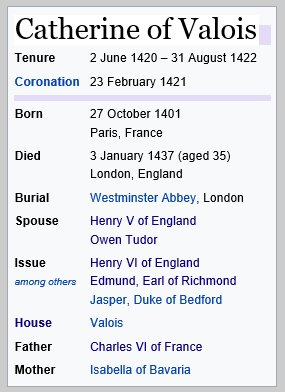

Did you

answer Catherine of Valois? Considering her

picture is hard to miss, that would be a good guess,

but we are still not quite there yet.

The best

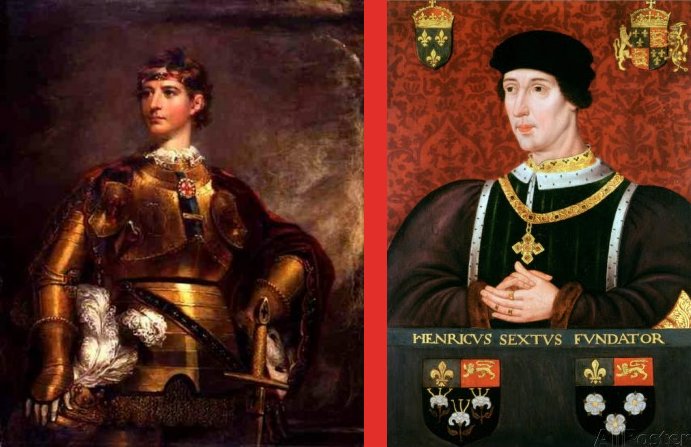

answer is Henry the Sixth.

Mad King Henry the Sixth was the direct

descendant of Mad

King Charles the Sixth. The

humiliating defeat of

Agincourt took place during the reign of Charles

VI. With Charles incapacitated at the time of

Agincourt, his wife Isabelle allowed King Henry V,

the enemy, to marry beautiful daughter Catherine

Valois (who just happened to be a little nutty

herself).

This

marriage inadvertently linked Catherine to one of

the greatest ironies in history. Catherine

would inadvertently carry out the revenge of French

King Charles VI on England. As we know,

Catherine passed on the seed of madness to her son, the sad, bewildered

King Henry VI. It seems almost karmic that by marrying his daughter Catherine

to Henry V, hero of Agincourt, Charles made

sure his family's hereditary madness crossed the English Channel.

|

Here is

a sad reality... England was absurdly dominant over

France during the reign of Charles VI.

With the

Hundred Years War lasting from 1337 to 1453, out of

those 116 years, France did not gain the upper hand

until the final days of the conflict. What can

explain the change in momentum? Henry VI.

The

historians will say Charles VI died in 1422 and

Charles VII, better known as 'Charles the

Victorious', took over. The historians

will also point out that Henry V, a fierce warrior,

died the exact same year.

And who

took his place? Henry VI.

England's king had gone from a stud to a simpleton.

The

course of the war changed instantly. But Henry

VI wasn't done yet. When the Hundred Years War

ended in 1453, a new war took its place. 1453

was the start date of a new conflict. Henry's

madness created the War of the Roses. Surely

in the French equivalent of Valhalla, Charles VI was

laughing.

|

|

Illegitimacy and

the Throne

|

| |

|

A major

scourge of the 21st Century are computer viruses.

Charles VI had planted a time bomb virus of another

sort in the English bloodline. The mental illness of

Catherine's son King Henry VI was more responsible

for the War of the Roses than any other factor

because it encouraged the subsequent free for all

power grab. When a King goes mad, the country

goes to hell. And when the country goes to

hell, it is usually because there is a power vacuum

at the top. The madness of Charles had led to the devastation of

France during the Hundred Years War. Now that

same madness gave

England its equally destructive War of the Roses by

encouraging the power hungry nobles and relatives to

seize power for themselves.

Let us

review the damage caused by Henry VI.

•

His

incompetence led to England's humiliating collapse

at the end of the Hundred Years War.

•

His

weakness led to the enormous social and political

problems in England which led to the War of the

Roses.

•

His

inability to reproduce led his wife to have the

affair with Edmund Beaufort which led to Edward of

Westminster.

If not

for Edward's miracle victory at the Battle of

Barnet, England would have had its next illegitimate

king.

'Next'

illegitimate king? Uh oh.

Let's be

clear on something... there is current DNA evidence

that proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that

illegitimacy occurred somewhere in the English line

of kings, perhaps even several times. For

example, we might recall the story where King Edward

the Fourth's own mother, Duchess Cecily Neville,

claimed her son Edward was the illegitimate spawn of

her fling with an obscure archer. It is said

that Edward was very good with a bow and better

looking than his mother's husband. Surely that

is all the proof we need.

England

may have dodged the illegitimacy problem with Henry

VI, but his mother Catherine went out and made

things much worse. Yes, indeed, as it turned

out, Catherine of Valois was not through wreaking

her reproductive damage upon England.

Catherine was

the gift that kept on giving. England

mistreated her, so she mistreated England right

back. Not only did she give

England her father's madness, there is a strong possibility that

Catherine gave England

its next illegitimate king.

Personally, I have never understood why people make

such a big case out of illegitimate birth. I

hate the way people look down on a bastard child.

Why punish the child for the sins of the parents?

To me, the child should be judged on the quality of

his or her actions, not the parentage. For

example, England's William the Conqueror was born a

bastard and look what he accomplished.

However,

I also understand that various religions contend

that children born out of wedlock must carry a

stigma. This consideration may not be

important to me, but it is to some people. I

guess illegitimacy is one of those issues where one

has to make up their own mind.

One of

the interesting things about illegitimate kings is

the possibility that the bastard child may be a

much-needed 'upgrade'. For

example, Russia's Catherine the Great was married to

an idiot named Peter the Third. Her son Paul

was the likely product of Catherine's affair with

Sergei Saltykov, a talented Russian officer.

Paul very easily could have been one of Russia's

great rulers. Unfortunately he was

assassinated five years into his reign. And

why was that? Paul did something unforgivable.

Paul had the nerve to help the miserable serfs. In

fact, he was Russia's version of Robin Hood - steal

from the rich and give to the poor. That got

him killed.

Ah, but

I digress. Back to England. Margaret of

Anjou had spent seven years waiting for Henry VI to

impregnate her. Without an heir, Richard of

York threatened to claim the throne. So what

is a girl to do?

This

offers the perfect opportunity to tell a dirty joke.

So Mrs. Smith, pregnant with her first child

after such a long wait, visits her neighbor's

barn to buy some eggs.

Mrs. Smith, "Oh, Farmer John, look at all the

hens you have! Last time I was here, you

had only half as many. Where did you get

so many hens?"

Farmer John, "It wasn't that hard. The

previous rooster wasn't getting the job done, so

I switched cocks."

Mrs. Smith, "Interesting how that works."

More than likely, Margaret of Anjou's enduring love

affair with her favorite advisor produced Edward of

Westminster, the boy who died at Tewkesbury.

So was this child an upgrade? Tough question.

As the product of two ruthless, ambitious parents,

it is debatable how their reportedly cruel son would

have turned out as king. As it was, England

narrowly missed placing another illegitimate ruler

on throne. Oh, by the way, Joffrey on

Game of Thrones, Edward's Doppelgänger, was

also illegitimate.

When

looking for the break in the royal lineage, one

place the scholars always point to is Catherine of

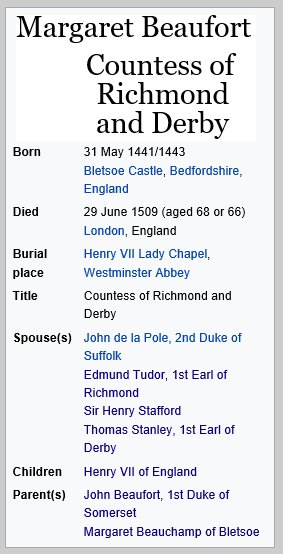

Valois. Catherine's son Edmund Tudor was born

in 1431, nine years after the death of her husband

Henry V. Catherine was a widow at the time.

There

are two kinds of illegitimate children. There

are children born out of wedlock and there are

children born of adulterous affairs. To me,

the allegation that Edward IV was the product of his

mother's liaison with a lowly archer as opposed to

his brilliant father is far more serious than

Catherine giving birth to a child while she was

single and forbidden to marry.

'Forbidden

to marry'?? Surely there is a story here

and indeed there is.

| |

|

As

historic figures go, I would imagine very few people

today have the slightest clue who Catherine of

Valois is. Although she was immortalized by

Shakespeare as Henry V's 'Fair Catherine',

she has nevertheless remained an enigma with little

written about her. Long ago Catherine was

dismissed by historians as nothing

more than a perpetual footnote in the history of

this period. Through the centuries the story

of Catherine of Valois has largely been forgotten.

I find this surprising because my research shows

that Catherine unwittingly had a dramatic and

lasting impact on English history.

Perhaps

the key word here is 'unwitting'. By

reading between the lines of the narratives, I

gather that Catherine was pushed around her entire

life. Given the fact that she gave birth to a

simpleton (Henry VI) and showed no ambition for

politics suggests that Catherine herself

may not have been the sharpest knife in the drawer.

That said, her story dominated the 15th century

tabloids. Catherine's life was touched by

a cruel

childhood, mental illness, political mistreatment,

a clandestine

marriage, and secret

illegitimate children.

Catherine was

the youngest of eight

children born to King Charles VI of France and

Isabelle of Bavaria. We

already know that Catherine's father was a basket

case, but now we discover her mother was just as

bad in a different way. Her mother, Isabelle, was

haughty, callous, and shamelessly adulterous to

Catherine's

poor ailing father. Isabelle took advantage of

the king’s frailties and seized control of the

kingdom from usurpers. Isabelle was so busy

with politics, poor Catherine and her siblings were

neglected. As opposed to the pampered life of

a princess one would expect, Catherine and her

siblings would live like paupers in miserable

surroundings.

|

|

| |

|

As

King Charles continued his

descent to madness, Isabelle decided to hide

the King from the public.

When Catherine was 3, her mother moved Charles from

the palace and placed him

in a royal Paris residence

known as Hotel de Saint Pol

along with his children. Catherine

was nowhere near the corridors of power as a

child... and that's the way her mother wanted it.

Out of sight, out of mind.

Isabelle's

mission completed, the wildly unpopular Queen

devoted her time to the pursuit of

pleasure, pilfering the treasury, and showering her

favorites with riches. In contrast, contemporary

chroniclers noted the 'piteous state' of the young

Princess Catherine and her siblings, 'nearly starved

and loathsome with dirt, having no change of

clothes, nor even of linen'. The Queen was so

negligent that she made no provision for her husband

and children. Content that they remain locked away

far from sight, she neglected to ensure that the

servants at Saint Pol were being paid for their

labor. Consequently, as time went on,

many were forced to find work elsewhere, leaving

the royal children and their ailing father wholly

dependent on the few faithful servants who remained.

There is

much more intrigue I could add about Catherine's

childhood, but let's just say that

Isabelle

invested little energy in her child's welfare.

Isabelle

was an ambitious woman with a cruel and ruthless

determination to advance her own affairs.

It was Isabelle who decided

to use her young daughter Catherine as a bargaining

chip with Henry V, the powerful king of England.

As we

know, the marriage ended in the tragic death of

Henry V to dysentery.

Catherine had the briefest of reigns as the queen

consort of England from 1420 until 1422. She

gave birth to crown heir Henry VI in December 1421.

With her husband over in France conducting yet

another war, it is said that Henry V died without

once seeing his son. Catherine's grief was

reported to be most violent.

Time

passed. Seemingly content to remain somewhat

aloof, Catherine made no strong alliances one way or

the other while in mourning. Some say the

Queen Dowager was in an incredibly powerful

position. Catherine was young, attractive and

wealthy as well as the mother of the King of France

and England. Unfortunately, she didn't act

very powerful. Thanks in large part to her

sad, pathetic childhood, Catherine had little

ambition of her own and virtually no instincts for

playing politics. In a sense, she was a

shy weakling just as her royal son would turn

out to be. Her English was poor and she had

few friends in high places on the English council.

But she was still Fair Catherine... men came to

visit.

The

Council did not know what to do with Catherine.

Another marriage involving Catherine could spell

disaster for internal English politics as well as

complicate their current standing with France.

Worried that Catherine would raise her child to have

French sympathies, in 1425 Catherine's regent

Humphrey decided that young King Henry VI, 4, should

be removed from his mother’s care and placed into a

separate household. Catherine's new role

became more like that of a favored aunt. She

could see the child from time to time, but was

removed on a daily basis. Reports say that

Catherine appeared to accept this and be content

with her role. If so, her passivity gives us a

major clue. What normal mother would accept

this arrangement? We certainly could never

imagine Margaret of Anjou letting a similar thing

happen to her beloved Joffrey, er, Edward.

With her

husband dead, once her

child was taken away, it seems like Catherine's remaining

purpose in life had been badly damaged.

Catherine of

Valois was

now a

25-year old widow with no children, living in the

wrong country, and nothing to do. Rich and

beautiful, it is no surprise that Catherine

fell in with the younger set at court.

At this time, Catherine was said to have

difficulty “curbing her carnal passions”.

Don't we all? Some handle

it better than others, but Catherine apparently let

her Scorpio nature get the better of her.

It was

only a matter of time before a girl looking for a

good time ran into a very bad boy.

|

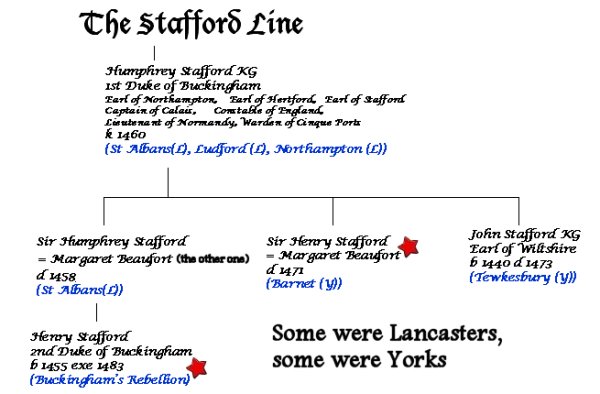

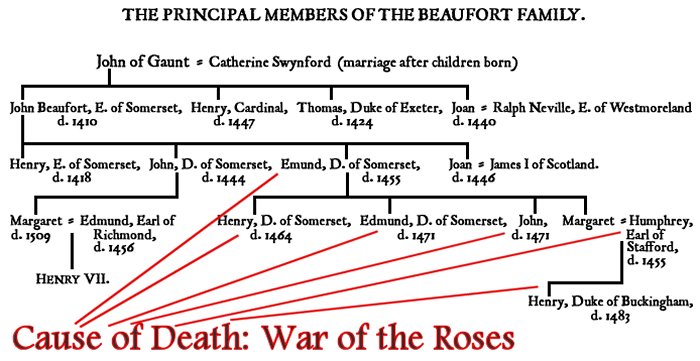

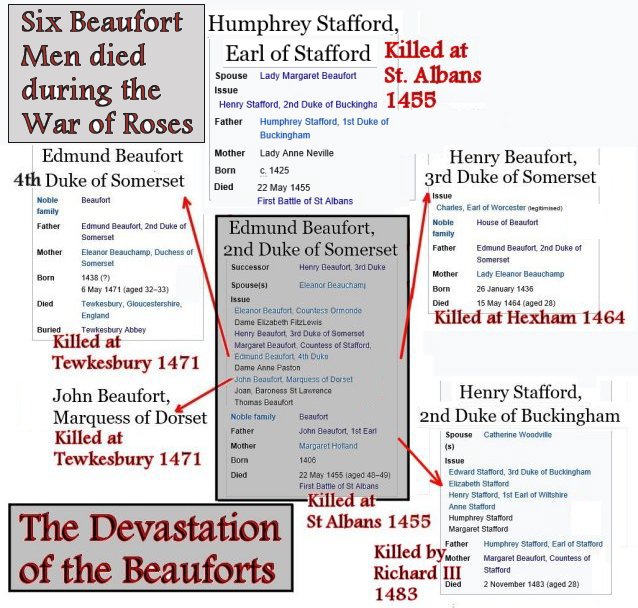

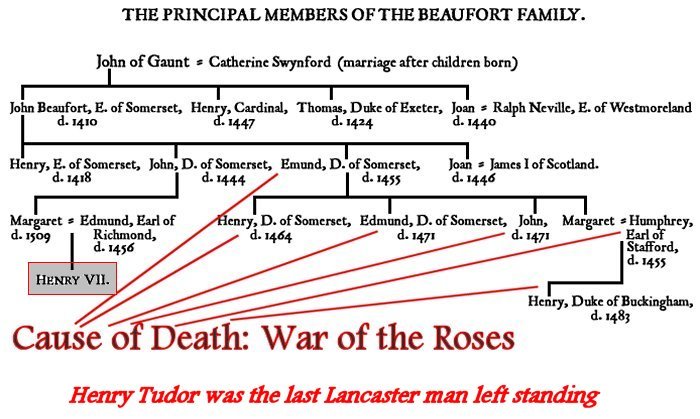

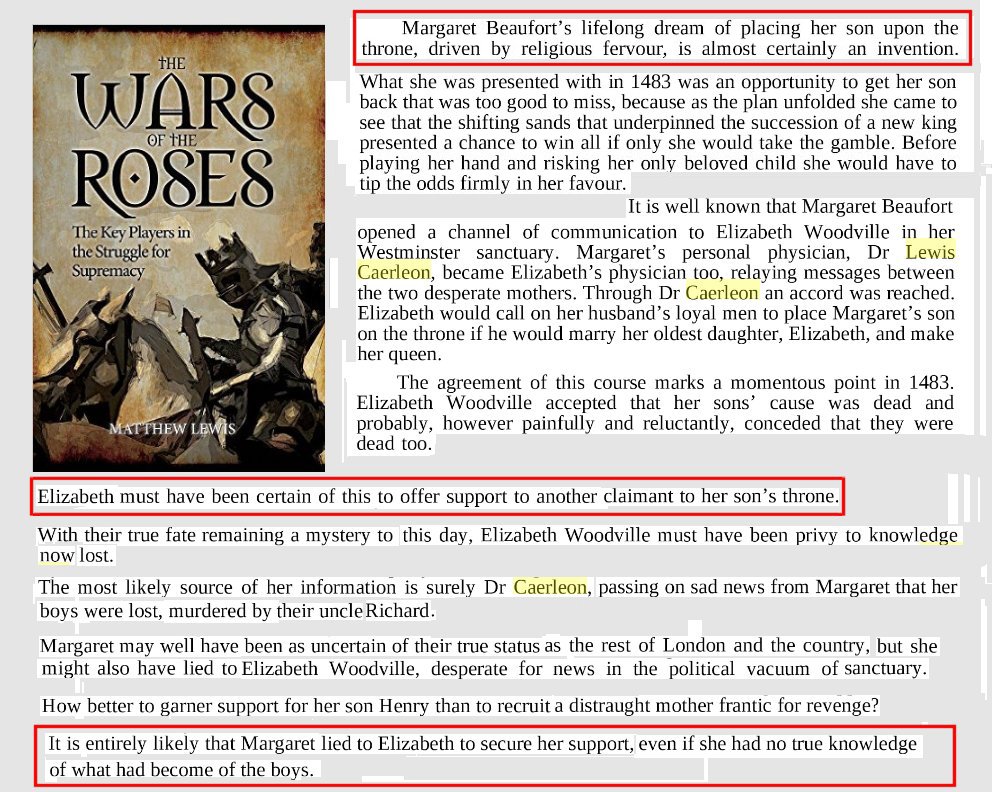

If nothing

else, the War of the Roses is the story of ambition

gone mad.

In

particular, Catherine became infatuated with

the highly ambitious Edmund Beaufort,

an emerging political figure.

Edmund Beaufort...

where have we heard that name before? This is

the same Edmund Beaufort who was the major political

rival of Richard, Duke of York, back in Act One of

our narrative.

Edmund Beaufort was not just the

main advisor to Margaret of Anjou, he was also her

boyfriend. Edmund

Beaufort was likely responsible for

impregnating Margaret with her son Edward.

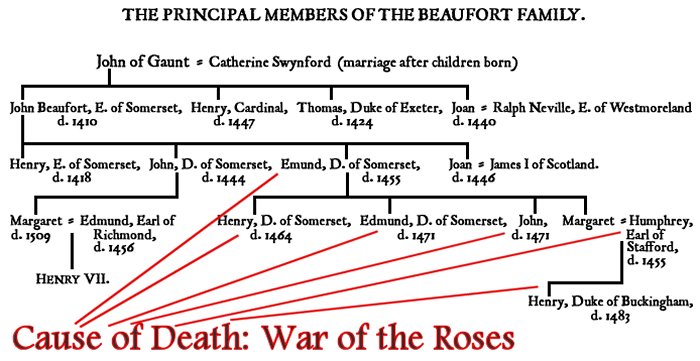

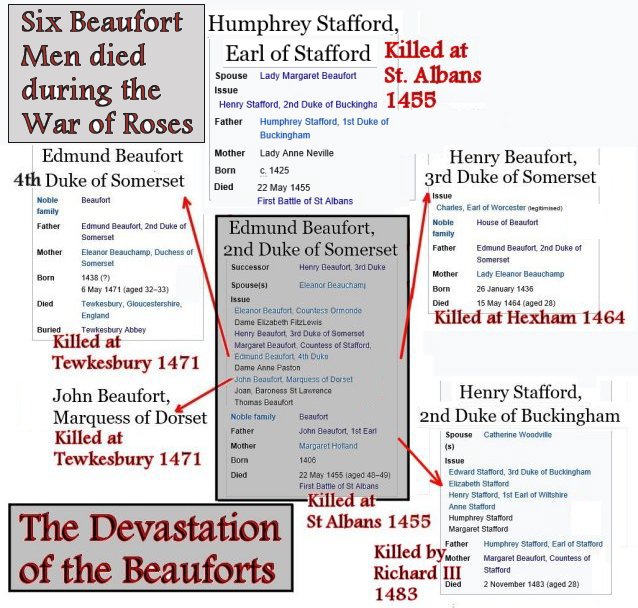

Sad to

say, Edmund Beaufort's ambition would cost him

dearly. His decision to back Margaret of Anjou

throughout the War of Roses would doom two

generations of his Lancaster-based family to death.

Thanks

in large part to Edmund Beaufort, the entire male

side of his Beaufort family was obliterated.

Can you even imagine? Six men died fighting!!

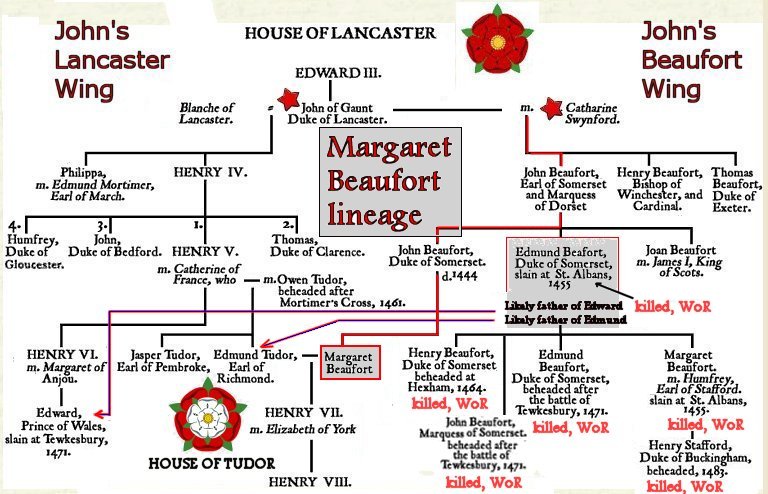

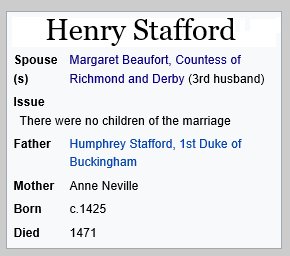

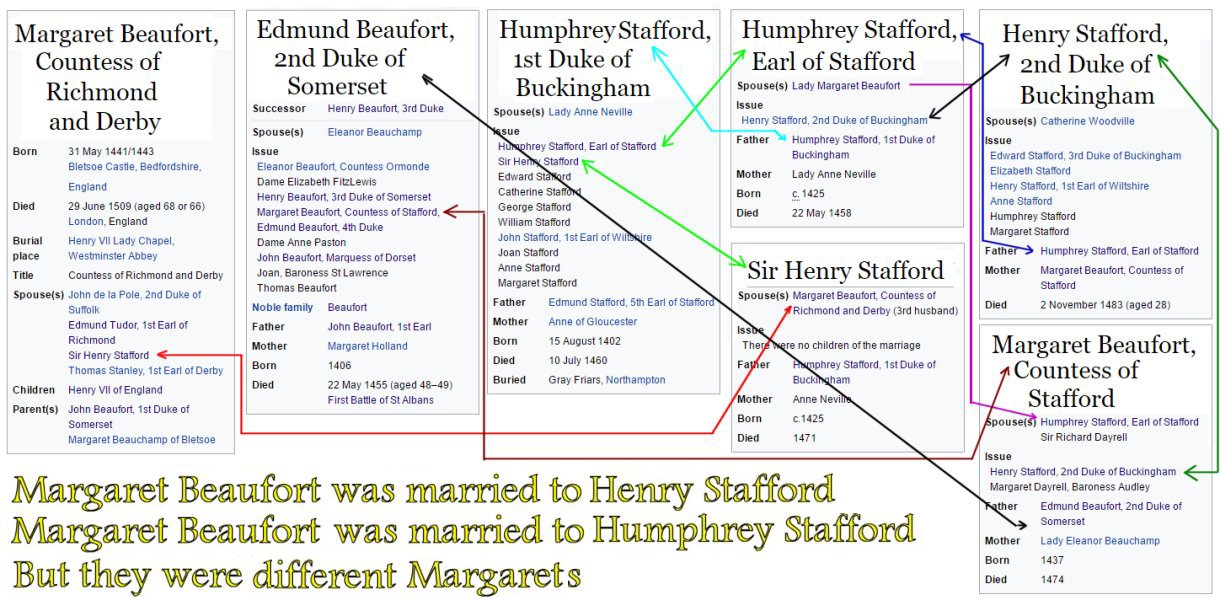

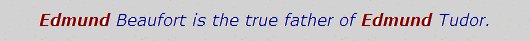

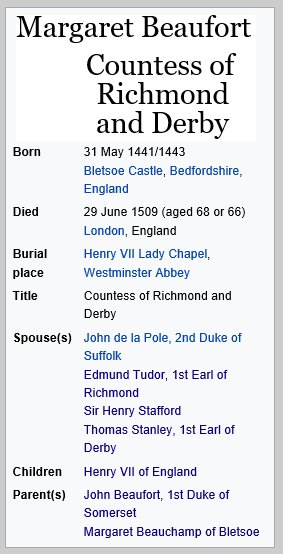

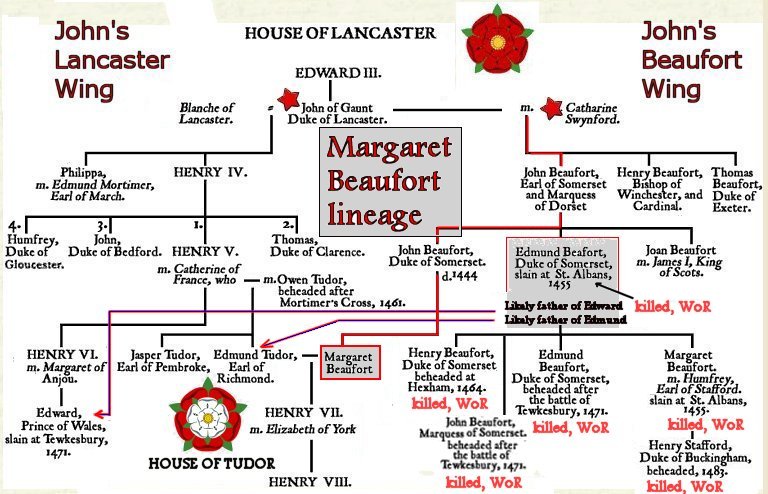

However,

perhaps Edmund Beaufort got the last laugh.

Back in his younger days, it is very likely Edmund

was the true father of Edmund Tudor, the man who

would in turn sire Henry VII, the future king

of England.

So was

it love or lust between Fair Catherine and Edmund

Beaufort? Or was it her untold wealth?

For that matter, the next boy to emerge from her

womb would have a claim to be the future King of

France.

In very

simple terms, Catherine was a good catch.

Maybe too good a catch... her Regents were very

alarmed at this romance, especially when Edmund, 22,

asked permission to marry Catherine, 27.

Enter

Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, to the stage.

Humphrey was not only the current Regent of England,

but as the uncle of the child Henry VI, he was also the

child's Lord Protector.

When

Humphrey heard the rumor in 1428 that Edmund

Beaufort sought to marry

Henry's mother, Humphrey put his

foot down and said no.

With

Cardinal Henry Beaufort as his main political rival,

the last thing Humphrey wanted to do was to muddy

the waters by giving more power to yet another

Über-ambitious Beaufort.

|

|

Humphrey feared that if this highly

desirable young widow decided to marry, her Beaufort husband

might gain undue influence over his young stepson

(Henry VI) and upset the balance of power.

Catherine's French nationality was never far from the

minds of the Council. If she should decide to

ally herself with a member of the French nobility,

the situation would be even more fraught with

difficulties.

Such was

the fear of remarriage that Parliament was persuaded

to pass a 1428 law prohibiting any person from

marrying the dowager queen without the consent of

the King and Council. They played a dirty

trick on Catherine... there was no king at the time

to give permission!! The country was being

ruled by Humphrey who was 'not a king'. If Catherine wanted to marry

Edmund, she would have to wait nine years until her

son Henry, 6, came of age in 1437. So

much for Catherine's hopes to remarry.

No doubt

Edmund gave up all hope of marrying Catherine.

A deeply ambitious man, Edmund wasn't about to

jeopardize his career by risking marriage to a

Forbidden Woman. On the other hand, there was

no law that prevented Edmund from continuing to see

Catherine under the radar and under the blankets.

England is a very chilly place and what better place

to seek warmth than the arms of a beautiful

woman?

No doubt

the Council thought itself clever to disempower the

Dowager Queen, but there is a real chance their

decision backfired in a very remarkable way. One can easily imagine the

intense bitterness Catherine felt at having her love

life so blatantly interfered with. No one

likes being unfairly pushed around. Therefore it comes as

no surprise that Catherine may have rebelled in a

very unusual way.

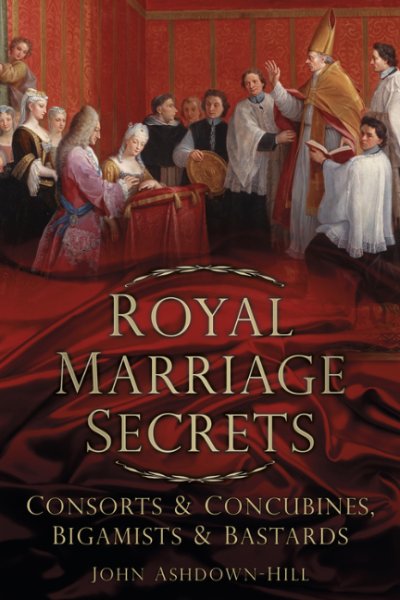

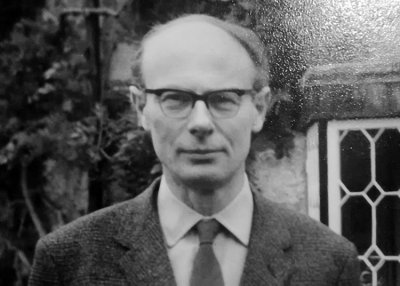

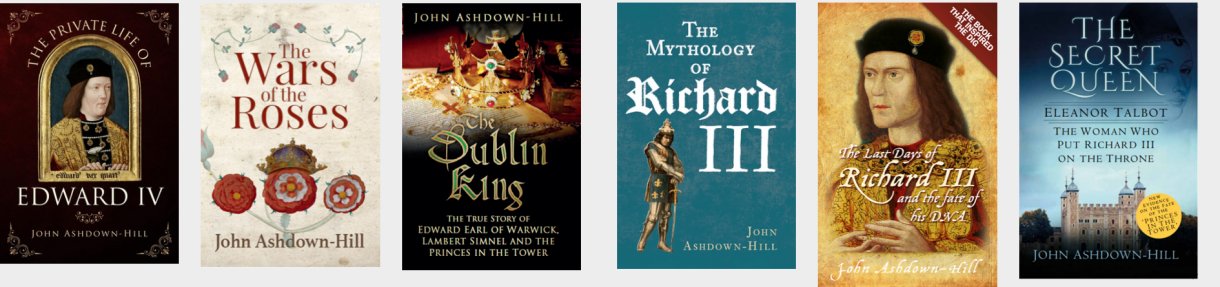

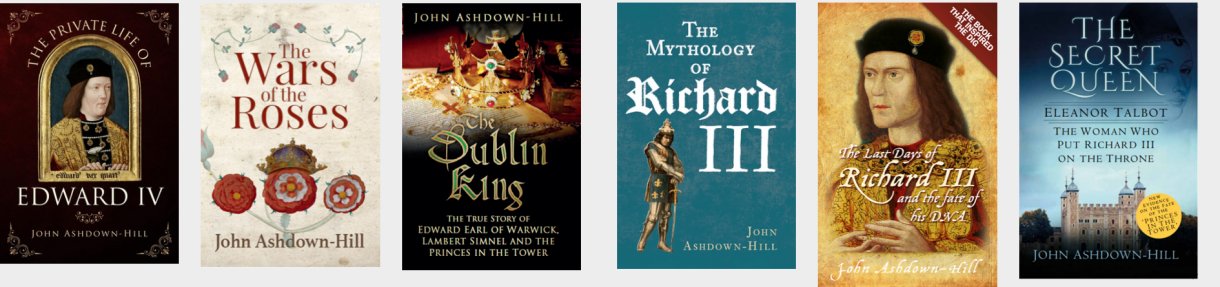

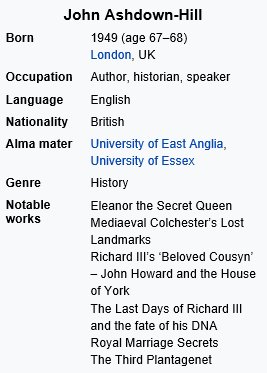

In 2013

historian John Ashdown-Hill published a book called

Royal Marriage Secrets. In his

book Ashdown-Hill said he had uncovered evidence

that Edmund Tudor, father of Henry VII, was not the

son of Owen Tudor but rather that of Edmund

Beaufort.

Needless

to say, this ignited considerable controversy.

Many erudite people wrote long rebuttals to

deny Ashdown-Hill's claims. Other people said this

proved what they had believed for a long time.

Still others read the book and decided they had a

better claim to be King or Queen of England than the

current royal family. Lord knows, we might

just have another War of the Roses right here in the

21st Century.

|

|

| |

|

In the

meantime, I have one word of wisdom. Since the

English take these matters very seriously, if you

ever visit England, don't make any jokes about the

legitimacy of various kings. After all, due to

King Edward III siring dozens upon dozens of children, 99% of all

English citizens have at least a few drops of royal blood in them.

For that

matter, maybe I am related to that Archer who got

Cicely Neville pregnant with future king Edward the

Fourth. I think I will start a rebellion when

I visit England. What a shame it is that

Shakespeare isn't still around to write 'Richard the

Fourth'.

|

| |

|

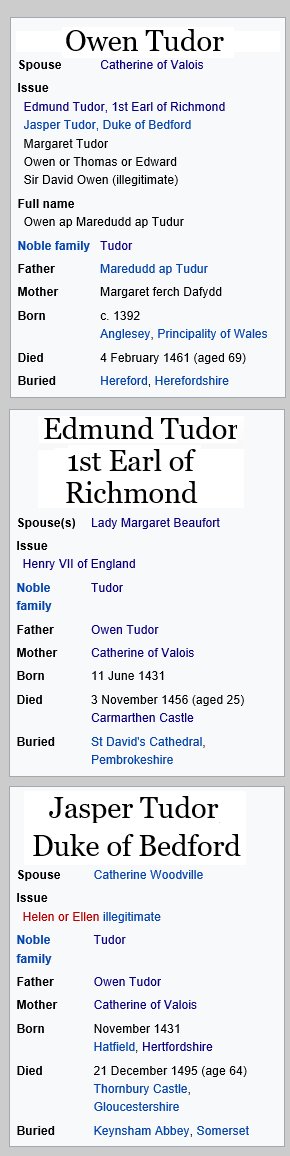

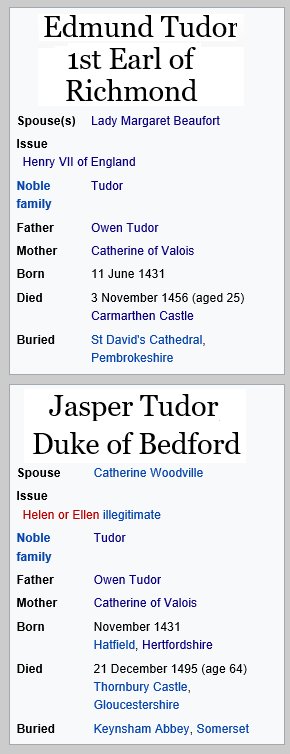

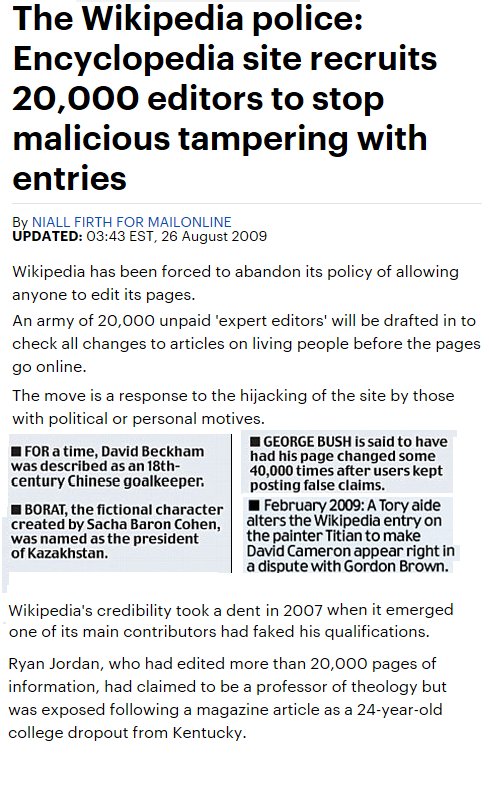

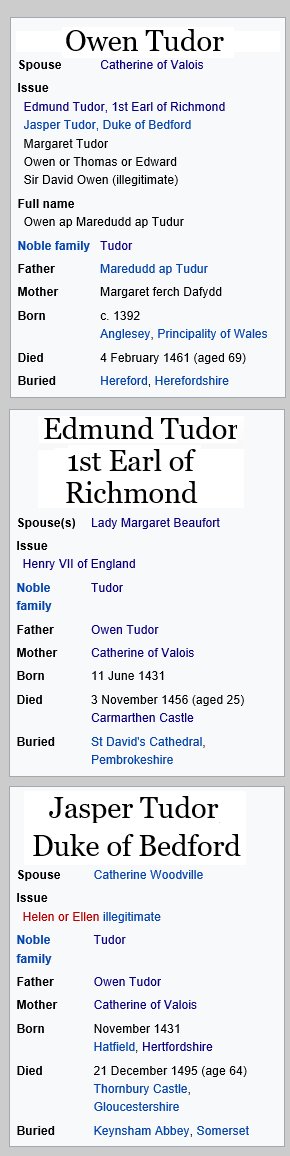

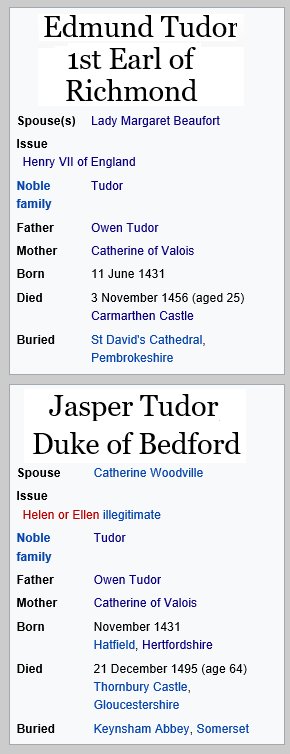

Owen Tudor is the man who

allegedly fathered Edmund

Tudor by Catherine of Valois, the former Queen of

England.

Edmund

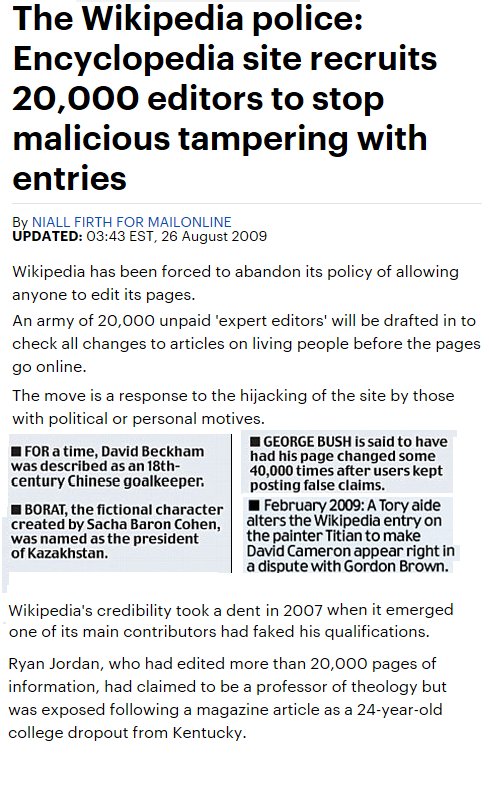

Tudor would later father Henry Tudor who went to

become Henry VII, the

first Tudor king of England.

Henry VII could point to his paternal

grandmother Catherine of Valois as the source of his

Royal Blood.

However,

there was problem after problem with Henry's family

tree.

One

problem was that Edmund Tudor was mostly likely a

bastard.

Another

problem was that Owen Tudor probably wasn't Edmund

Tudor's father to begin with.

Embarrassing as this sounds, Edmund Tudor's mother

was a Beaufort and Edmund Tudor's father was a

Beaufort. If this is true, then it

means the royal house of 'Tudor'

sprang from Beauforts on both sides. In other

words, his parents were first cousins!!

Except

that History doesn't see it that way. History

tells us Owen Tudor, a very unremarkable man, was a

servant who allegedly seduced the former Queen of

England. So how did he do it? How did a

lowly servant persuade a woman with the highest

prestige into his bed?

In other

words, if the truth had been known, there would have

been great scandal. So a whopper of a

tale was created to keep the true parentage of Henry

VII a complete secret.

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

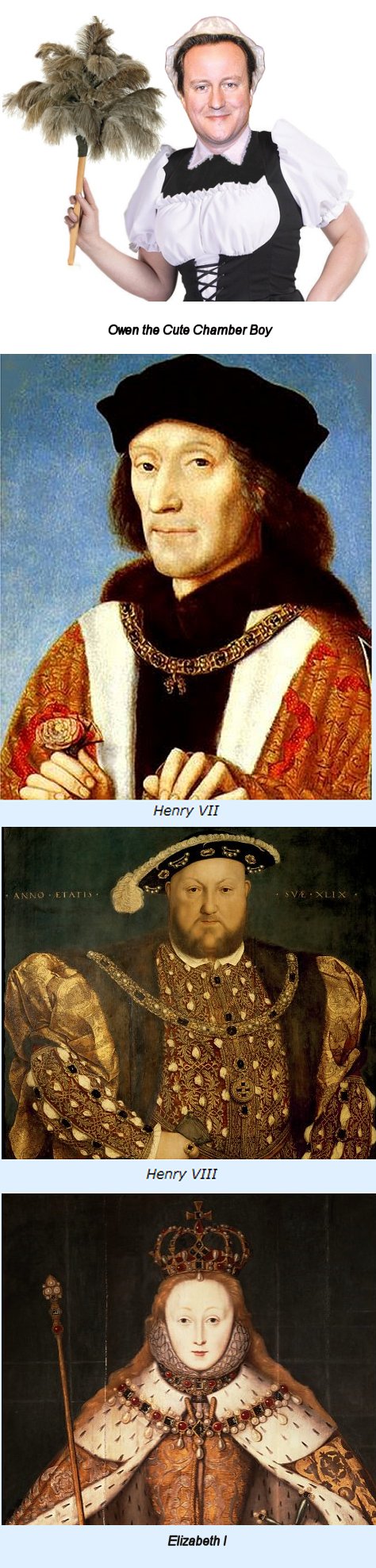

It is

said that Queen Catherine of Valois found Owen to be

so irresistible that she gave her heart, soul... and

yes, body... to this handsome young man.

No big

deal until we realize that Owen was not an estate

owner with a pedigree and vast lands under his

control. No, not hardly. Owen Tudor was

not exactly high-born. In fact, he was the

lowly son of a Welsh rebel who became a servant in

Catherine's wardrobe department

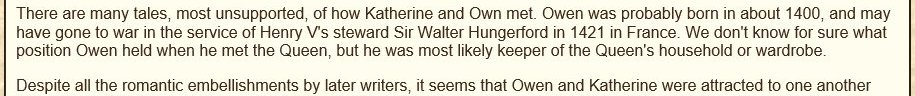

This is

one of the most curious stories of parentage

imaginable. By favoring this particular

servant with her charms, some of England's most

famous kings.... Henry the Seventh, Henry the Eighth

and Elizabeth the First could point to a lowly

chamber boy as their forefather. Impressive,

yes?

Or maybe

not. Considering my own roots include a Welsh

undertaker gracing the family tree, finally I have a

story I can relate to! Oh, the shame of it

all.

Since

Owen Tudor is the newest member of our narrative,

let us introduce him properly. Born in 1400,

Owen was a nobody who worked in the household of the

Dowager Queen and somehow ended up in the Queen's

bed. It is said that their lovemaking produced

a boy named Edmund Tudor, the eventual

father of Henry VII, the king who

would begin the Tudor dynasty of England.

This is

a very curious story. We hear rumors of

powerful men who inveigle or coerce susceptible

chambermaids into their bed and then discard them

quickly. What we don't hear very often are

stories of a beautiful Queen, a woman coveted by

extraordinary men in high places, who chooses

instead to seduce the keeper of her wardrobe and

linen. But no, the story doesn't stop there.

The chamber boy impregnates the Queen. Oh, darn, well,

these things happen. Just ask Cecily Neville,

victim of that handsome Archer boy.

Big

deal. So, all Catherine has to do is find some

noble and ask him to be noble and cover it up.

Or have the child on the sly and hand it to some

peasant to raise. But no, the Queen keeps the

child!! And why? Because she has fallen

in love with Chamber Boy! She leaves the

palace with chamber boy and they live happily ever

after out in the countryside, having four more children along the way. What a

remarkable story!

In 1421

Owen is said to have gone to war in France.

However, he was not a warrior. Instead Owen

assisted Sir Walter Hungerford, a steward in the

service of Henry V (Agincourt). Following

Henry's death, Owen somehow ended up as a keeper of

the Queen's household or wardrobe back in England.

Virtually nothing is known about how the liaison

between Catherine and Owen took place.

Consequently there are all sorts of 'Legends'

about their meeting, which is another way of saying

that someone decided to make up stories.

For

example, one writer said that Owen came to the

queen's attention when she spied him bathing naked.

Another chronicler dwelt upon Owen's good looks

which the Queen Mother noticed, causing her to give

the handsome squire a post in her household.

And then there was the legend that Owen either

deliberately or accidentally fell onto the queen's

lap during a drunken dance.

My

favorite was the lap story. While on guard at

Windsor Castle during some festivities, Owen was

required to dance before the court. Queen

Catherine sat on a low seat surrounded by her

ladies. While making an elaborate pirouette, the

unfortunate man lost his balance and fell headfirst

into the Queen's lap. The Queen's manner of

excusing this was so awkward that her ladies in

waiting grew suspicious that the Queen had a thing

for this handsome Welshman.

Whatever

the true story, there can be no doubt that Catherine

and Owen were taking a huge risk. Catherine

lived in the king's household, presumably so she

could care for her young son when called upon, but

mostly so the councilors could watch over the Queen

herself. Knowing full well there were spies

everywhere, Owen and Catherine's mad love affair was

sheer madness.

Seriously, this story is so far-fetched it

absolutely stretches the imagination. We are

supposed to believe the man who won Catherine body

and soul, the man for whom she risked everything,

was her handsome Clerk of the Wardrobe! A trumpet

for the strumpet, please! If this were

fiction, I'd toss the book in the trash as rubbish.

But that is apparently more or less what happened.

(Or

at least that is what they would have us believe!!)

Despite

all the risks, the Queen and the servant began their

affair right under the noses of people who were paid

to watch her. The queen was under suspicion.

She was a foreigner with few friends. Many

suspected Catherine of secretly supporting her

brother Louis VII's claim to the French crown over

her that of own son little Henry VI.

Personally, I think there has to be a more likely

explanation for this unlikely pairing. One

explanation would be rebellion. The assholes,

oops, I meant the dignitaries who ruled England in

the name of Catherine's son expected the queen to be

content to sleep with her fond memories of the great

Henry the Fifth. One can assume Catherine felt

considerable resentment.

One

might even conclude her affair with Owen was her way

of thumbing her nose at these men. Perhaps

this good-looking servant was the only option

available to a desperately lonely woman trapped in a

cold, unfriendly castle.

Thus

began the mad love affair between the widow of the

revered King Henry and her studly Clerk of the

Wardrobe. I say 'mad' because the two

risked a charge of treason. Based on that

crazy statute, one or both of them could easily end

up in jail... or worse. We've heard of men who

lose their head over a woman, but in this case, it

could really happen!

Then one

day Catherine realized she was pregnant. Uh

oh.

All the

history books point to Owen Tudor as the father.

Maybe the thing to do here is to read between the

Lies. First Owen risks his neck to impregnate

the Forbidden Queen and then Catherine turns around

and names her son 'Edmund'.

Huh?

'Edmund'. Such a curious choice of

names. Edmund was the name of Catherine's

former boyfriend. Are we missing something here???

|

|

|

|

|

The 11

December 2016 episode of the TV show The

Royals revolved around the legendary story

of Owen and Catherine. As one can see, their

tale was an "epic, earth-shattering love

affair!"

Forgive

me, Father, for I am about to be catty.

As I

read further, I realized the writer of the 'earth-shattering

love affair' blog had basically accepted the

Owen-Catherine Fairy Tale hook, line, and

sinker. I doubt very seriously the writer dug

very deeply into the story. This is not

necessarily a good thing. After all, it is my

understanding that the motto of most TV shows is 'Why

let the truth get in the way of a good story?'

It is

scary to realize most of our history lessons these

days come from movies and television.

Currently our world is awash in a phenomenon known

as 'Fake News'. There has probably never been

a time when ignorance and superficial thinking has

been more prevalent. We base our decisions on

the words of people we don't know personally.

This may not be a very good idea. Rumor has it

our leaders deliberately tell fibs from time to

time.

I

suppose I am just as guilty as the rest of

superficial thought. I have based this entire

story about the War of the Roses on the ten

listings that appear on the First page of Google.

I pick a few a random and take a peek. If it

sounds intelligent, I borrow a few ideas. But

that doesn't mean they are correct. Most of

the time, I don't even know the name of the author.

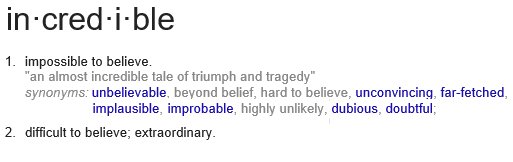

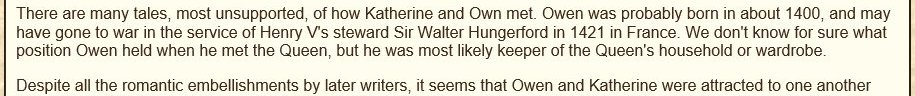

Research

these days is little more than cut and paste.

It is shocking in a way how many websites simply

repeat what another website says VERBATIM. For

example, Wikipedia, the source for many of my

explanations, makes it effortless to cut and paste

passages into my stories. I love Wikipedia,

but I don't always trust it.

Every

now and then, I stop and think about it... I am

repeating the words of Wikipedia contributors who I

know nothing about. Here's another old

saying... you get what you pay for.

Wikipedia is free. The entire site was created

by volunteers. Who vets the Wikipedia writers?

I am

about to challenge the 'Owen-Catherine Fairy Tale'.

I believe this particular legend may not be what it

seems. In a sense, I will attempt to rewrite

history. If you find yourself agreeing with my

line of thinking, before you make up your mind,

please remember to ask yourself this question:

Do you really want to form your opinion based on

the words of a retired dance teacher who gets

his information from the Internet?

It all

boils down to Credibility. Question

everything, my friend.

|

|

Scandal in the

Castle: Who's Your Daddy???

|

I

contend that the

weird circumstances surrounding Catherine's

pregnancy suggests an alternative explanation for

Catherine's risky behavior... Edmund Beaufort.

No one

is quite sure when Catherine's affair with Owen

Tudor began.

•

One

website suggested 'somewhere between 1427

and 1429'.

•

Another

website reported 'About 1428 or 1429'.

•

Another

website reported, 'Despite all of this, Catherine

did remarry in secret, sometime in 1431 or

1432'.

•

A

third website said, 'It is accepted that

Catherine and Owen were married sometime around

1429/30'.

I am not

making this up. In fact, I'm not making any of

this up. I just drift from website to website

compiling the information, then I try to sort it

out. Do you know what the words 'Somewhere', 'About',

'Sometime', and 'Around' mean to me?

These

words mean someone is guessing. It means no one

knows the truth about these dates because both the

affair between Catherine and Edmund and the affair

between Catherine and Owen were conducted in secret.

I would place a bet that there are no existing

written accounts of what took place in the castle.

The

passage above is another good example of the general

fuzziness surrounding Owen and Catherine's supposed

Love Story. I am starting to believe we have a

genuine mystery on our hands.

•

'many

tales, unsupported...'

In other words, no one knows

the true story of how Owen and Catherine hooked up.

•

'We

don't know for sure what position Owen held.'

This suggests that no

one ever wrote any history of this liaison.

•

'Despite

all the romantic embellishments by later writers.'

Someone makes stuff up

like the 'Lap Story' and the next person buys

it.

•

'It

seems that Owen and Catherine were attracted to one

another.'

Gee, can we possibly be less

certain about this?

I believe

the words above are the words of an ethical writer.

This person has taken a good look at the existing

data and realized this very well could be a fable of

some sort. Embarrassed at being forced to

regurgitate literary diatribe based on quicksand,

the writer has hedged his or her bet by qualifying

every single phrase for the simple reason that no

one has a clue what really happened.

So I

suggest we read between the lines... maybe there is

a cover-up going on here. Maybe this entire

love story is nothing more than putting lipstick on

a pig.

We

started this chapter by asking a question:

How did a lowly Welshman bed a Queen?

Six

centuries have passed since the Owen-Catherine Love

Story took place. Someone compared it to a 'Remarkable

Fairy Tale'. Every single writer focuses

on how incredible

it was that a highly desirable Queen could allow

herself to be seduced by

a lowly servant, a young man who actually risked

death to take this woman to bed.

Yes,

indeed, it all sounds very romantic, but at heart

the idea is preposterous when you stop and think

about. It is hard to believe the 'epic,

earth-shattering love affair' between Owen and

Catherine actually took place because it challenges

our reality-testing equipment to the extreme.

This story is absolutely begging for a better

explanation!!

I don't

deny something unusual took place between Owen and

Catherine. After all, while she was still

pregnant, Catherine left the comfort of the castle

with Owen and had four or five children by him over

the next few years while

living out in the country. The Queen

definitely built the final part of her life around

this man. That part is not in question.

| |

|

What I

am suggesting is that the Edmund Beaufort Rumor invites us to

reinterpret the initial stages

of the Love Story in a different

light. Since clearly no one really knows what

took place here, I have decided to offer my own

theory.

What would

Catherine do if Edmund Beaufort really was

the father?

The

truth is that a lowly Welshman does NOT bed a

Queen... but a Queen might bed a lowly Welshman

if she had a good reason.

Given

the general fuzziness regarding the time line, Catherine's

two affairs could very easily have overlapped in

some way.

Keep in mind that Edmund Beaufort was the

leader of the formidable House of Beaufort.

He had his entire career ahead of him.

He had possession of the vast lands known as

'Somerset' in southwest England.

Beaufort stood to lose everything.

Let us

return to that law forbidding Catherine to

marry. Some

highly vindictive men had made it a grave offense to

marry the Queen Dowager without their consent. That

law was passed in direct retaliation for Edmund

Beaufort's interest in Queen Catherine. Quite

likely, after the law was passed, extra scrutiny was

placed around the Queen just to be on the safe side.

Catherine began to look over her shoulder in case

spies lurked behind the curtains and under her bed.

Catherine had to do something to hide her

pregnancy before the spies figured it out.

If

Edmund was responsible for Catherine's pregnancy, is

it possible that Catherine would turn to Owen in order

to protect Edmund?

|

|

| |

|

|

Gerald Harriss (1925-2014) was one of the

most distinguished English medievalists of

his generation. Harriss was an

eloquent interpreter of the workings of

English late-medieval political society,

illuminating not only its institutional

aspects but also the characters of its

leading actors, notably Cardinal Beaufort

(Edmund Beaufort's uncle).

As it turns out, I am not the only one with

a suspicious mind. In his book

Cardinal

Beaufort. A Study in Lancastrian Ascendency

and Decline,

Harriss

made

a strong case (pp.144,177-8)

for Edmund having

fathered one of

Catherine's later children.

Harriss had this to say about Edmund, Owen,

and Catherine:

Catherine may have

secretly married Owen Tudor to avoid the

penalties of breaking the statute of

1427–28. By its very nature the

evidence for Edmund 'Tudor's' parentage

is less than conclusive, but such facts

as can be assembled permit the disagreeable

possibility that Edmund 'Tudor' and

Margaret Beaufort were first cousins and

that the royal house of 'Tudor' sprang

in fact from Beauforts on both sides.

(Harriss,

178 n.34)

|

| |

|

Take

note that the

findings of Gerald Harriss concur

with that of John Ashdown-Hill. This means

the only two recent historians to analyze

this story have

come to the same likely

conclusion. To date, no one

else with similar qualifications has stepped forward

to challenge them.

One can

imagine after that nasty law was passed, Catherine had the right to retain her

boyfriend Edmund. She just couldn't marry him.

Quite likely

this roughshod treatment aroused a sense of defiance in the

two young lovers. Perhaps they rebelled and

continued to conduct their relationship in a private

manner.

If so, who can guess how long they continued to see

one another? One year? Two years?

Various

website's suggest

Catherine's romance with Edmund Beaufort had started

in 1928. She became pregnant with her son

Edmund Tudor in October 1930. So

what was the punishment for getting her knocked up??

No doubt the ensuing scandal would bring holy hell

down upon the head of the sperm donor. And

there very well could be danger too.

Do you

know what kings don't like? They don't like

babies being born with potential claims to the

throne. Just watch the rate babies get

executed on Game of Thrones in an

attempt to eliminate heirs.

Babies being born the former Queen of England were

exactly the kind of babies that made people nervous.

So if you don't believe the father of Edmund Tudor

wasn't in danger, guess again.

Now

let's pretend to enter the mind of some vindictive

asshole on the English Council.

Oh my God, a baby is about to be born to the

former Queen of England! If it is a boy,

thanks to Catherine's lineage, the child will

have a legitimate claim to the crown of France.

The Frenchies will absolutely flip out!

Furthermore, this kid could cause a lot of

trouble when he gets older. Edmund

Beaufort is a leading member of the House of

Lancaster and the House of Beaufort, two

prominent families with money and powerful

political friends. Whoever is king at the

time will have his hands full. Something

needs to done.

On the

other hand, what if the child belonged to Owen

Tudor?

Oh my God, a baby is about to be born to the

former Queen of England! If it is a boy,

the child will have a legitimate claim to the

crown of France. The Frenchies will absolutely

flip out! What was this idiot woman

thinking? However, we caught a break.

This Owen Tudor fellow is a lowly Welshman.

By law, the Welsh do not have the right to

ascend to the throne. No child born to

this man has any birthright, so we dodged a real

bullet here. Whew! That was a close

call.

| |

|

|

| |

|

Rick Archer's Note:

Before we continue, let me review the

mythology, er, rather the written history.

It has been reported

that Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset,

sought to marry the Dowager Queen and it

may very well have been that Katherine

returned these feelings. In

response, Parliament set out a statue

which stated that no man was allowed to

marry a former queen of England without

a special licence and permission from

the King.

If a man dared to

marry a former queen then not only would

he forfeit his lands and tenements, he

would also forfeit his life.

Edmund Beaufort, the Duke of Somerset,

paid heed to this statue and reined back

his intentions.

However, Owen Tudor

was a completely different story.

Reported to be a squire in the service

of the dowager queen, Owen Tudor soon

caught the queen's attention. There are

various stories as to how this happened,

one being that while dancing Owen fell

into the queen's lap, another being that

she spied him while he was swimming

naked. Whatever the true story is,

the pair married in secret, going

against the statute of parliament.

Soon

Owen Tudor

impregnated Queen Catherine with a boy